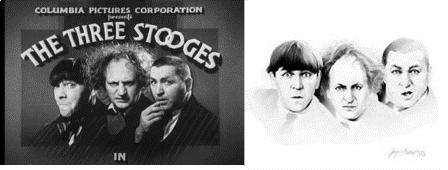

Not transformative: The Three Stooges (left) and artist’s literal depiction

Not transformative: The Three Stooges (left) and artist’s literal depiction

To help prepare for my right of publicity talk earlier this month with fellow Seattle attorney Mel Simburg, I came across this good summary of the “transformative use” doctrine, which courts have recognized as carving out a First Amendment exception to publicity rights claims.

Transformative use occurs when an artist embellishes the depiction of a personality rights holder, such that consumers purchase the good containing the depiction because of the artist’s rendering, rather than because the good depicts a celebrity or other personality rights holder.

A classic example of non-transformative use was artist Gary Saderup’s sketched rendering of The Three Stooges. It was a literal — almost photographic — depiction of the Stooges, which the California Supreme Court found consumers purchased because they liked The Three Stooges, rather than because of Mr. Saderup’s artistic rendering (skillful though it was). Because consumers purchased goods for the celebrity rather than an artistic comment on the celebrity, the court found the use was not transformative and, therefore, it was not excepted from California’s right of publicity statute. See Comedy III v. Saderup, 21 P.3d 797 (Calif. 2001).

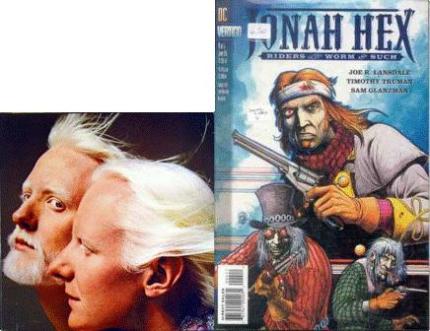

Transformative: Johnny and Edgar Winters (left) and embellished depiction

By contrast, sixties rockers Johnny and Edgar Winters’ right of publicity claim fell short against DC Comics in the same court two years later. The Winter brothers objected to their unauthorized depiction as “Johnny and Edgar Autumn” in DC Comics’ Jonah Hex comic book. Applying the transformative use test, the California Supreme Court found that the Winter brothers were merely the “raw materials” for the artist’s use in the comic book. Therefore, the court found the use was transformative and thus did not violate the brothers’ statutory right of publicity. See Winter v. DC Comics, 69 P.3d 473 (Calif. 2003).

As the article explains, which side of the divide a particular use falls on dictates whether it is likely excepted from a competing right of publicity; in other words, it dictates which interest wins: the celebrity’s right of publicity or the artist’s freedom of expression.

The article also identifies the states that recognize a statutory right of publicity, and states in which the right is descendible to heirs after death.

It’s good reading.