Ninth Circuit: “Identical or nearly identical” doesn’t control.

Ninth Circuit: “Identical or nearly identical” doesn’t control.

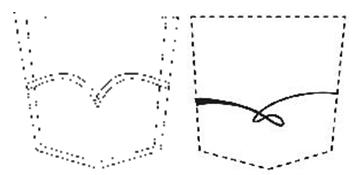

Levi’s and Abercrombie’s’ stitch designs

Interesting development in dilution in the Ninth Circuit.

Previously, Ninth Circuit courts required that a mark be “identical or nearly identical” to the plaintiff’s famous mark for dilution to exist.

That’s the standard the Northern District of California applied in Levi Strauss & Co. v. Abercrombie & Fitch Trading Company, a dilution case over the parties’ stitching designs. (STL post on the district court’s 2009 decision here.) The court noted the advisory jury had not found that Abercrombie’s “Ruehl” design and Levi’s “Arcuate” mark were “identical or nearly identical,” a standard that required that “the two marks … be similar enough that a significant segment of the target group of customers sees the two marks as essentially the same.” The district court likewise found the marks did not meet that standard and entered judgment for Abercrombie.

Levi Strauss appealed. It argued that nothing in the dilution statute requires the defendant’s mark be “identical or nearly identical.”

Abercrombie responded by arguing the subject language arose out of Ninth Circuit case law that continued to exist even after the Trademark Dilution Revision Act replaced the earlier Federal Trademark Dilution Act.

The Ninth Circuit considered the origin of the “identical or nearly identical” language. It found that even though the language predated the FTDA, the circuit embraced the standard because it believed it was rooted in that iteration of the statute. The court then noted the TDRA replaced the FTDA in broad strokes. That led the court to question whether a legacy standard should continue to control. It concluded the legacy standard was replaced when the FTDA was replaced.

“Several aspects of the TDRA are worth noting. The first, as mentioned previously, is that Congress did not merely make surgical linguistic changes to the FTDA in response to Moseley [v. V. Secret Catalogue, Inc., 537 U.S. 418 (2003), which required a showing of “actual dilution”]. Instead, Congress created a new, more comprehensive federal dilution act. Furthermore, any reference to the standards commonly employed by the courts of appeals — ‘identical,’ ‘nearly identical,’ or ‘substantially similar’ — are absent from the statute. The TDRA defines ‘dilution by blurring’ as the ‘association arising from the similarity between a mark or a trade name and a famous mark that impairs the distinctiveness of the famous mark.’ Moreover, in the non-exhaustive list of dilution factors that Congress set forth, the first is ‘[t]he degree of similarity between the mark or trade name and the famous mark.’ Thus, the text of the TDRA articulates a different standard for dilution from that which we utilized under the FTDA.”

The court found its departure from the “identical or nearly identical” standard was in line with the Second Circuit’s evaluation of Starbucks’ dilution claim based on use of the term CHARBUCKS for coffee in Starbucks Corp. v. Wolfe’s Borough Coffee, Inc., 588 F.3d 97 (2d Cir. 2009). In that case, the Second Circuit reversed the district court’s finding that the dissimilarity between CHARBUCKS and STARBUCKS was “sufficient to defeat [Starbucks’] blurring claim.” It instead found: “The post-TDRA federal dilution statute … provides us with a compelling reason to discard the ‘substantially similar’ requirement for federal dilution actions. … Although ‘similarity’ is an integral element in the definition of ‘blurring,’ we find it significant that the federal dilution statute does not use the words ‘very’ or ‘substantial’ in connection with the similarity factor to be considered in examining a federal dilution claim.”

In summary, a new statute means a new standard — or at least no basis for the Ninth Circuit’s old standard to live on. Therefore, the court reversed the district court’s decision and remanded for further proceedings.

The case cite is Levi Strauss & Co. v. Abercrombie & Fitch Trading Co., __ F.3d __, 2011 WL 383972, No. 09-16322 (9th Cir. Feb. 8, 2011).