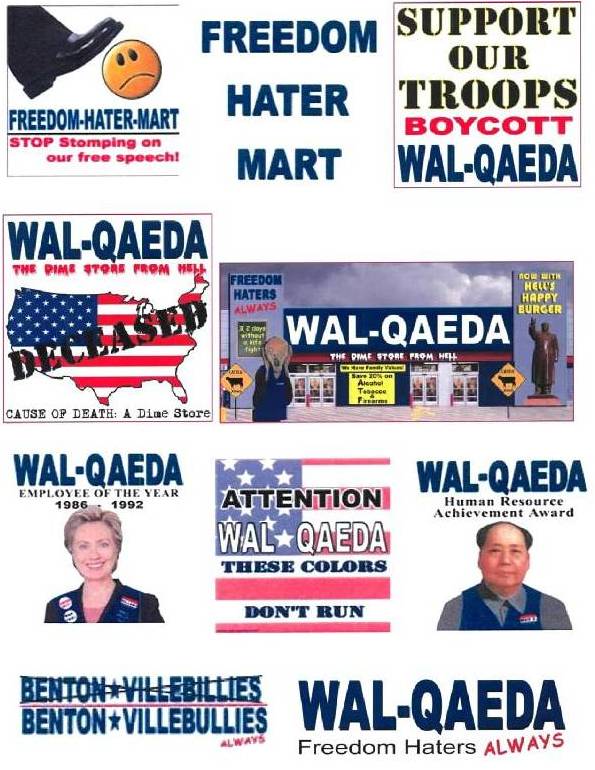

Not commerical, so no dilution: Charles Smith’s WAL-QAEDA parody

Not commerical, so no dilution: Charles Smith’s WAL-QAEDA parody

Discussing parody in my Advanced Trademark Law Seminar.

I’m stumped on one point.

In a number of cases involving the parodic use of a trademark, courts apply likelihood of confusion analysis to infringement claims. Successful parodies do not cause a likelihood of confusion, so they do not infringe trademark rights.

Analyzing dilution claims, however, courts in the same cases often treat parodies as noncommercial speech. For that reason, they conclude parodic uses are exempt from dilution claims.

In Smith v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 537 F.Supp.2d 1302 (N.D. Ga. 2008), for example, the court concluded Charles Smith’s use of WAL-QAEDA was not likely to confuse consumers with Wal-Mart’s trademarks, so Wal-Mart’s infringement claim against him could not stand. With respect to Wal-Mart’s dilution claim, the court found WAL-QAEDA succeeded as a parody because it communicated Mr. Smith’s negative feelings about Wal-Mart. “Thus, Smith’s parodic work is considered noncommercial speech and therefore not subject to Wal-Mart’s trademark dilution claims….” In other words, Mr. Smith’s parody did not trigger the dilution statute because it was noncommercial.

Similarly, in MasterCard Intern. Inc. v. Nader 2000 Primary Committee, Inc., 2004 WL 434404, *9 (S.D.N.Y.), the court found Ralph Nader’s use of MasterCard’s trademarks in a political ad that spoofed MasterCard’s “Priceless” advertising campaign was not likely to confuse consumers, so it dismissed MasterCard’s infringement claim. With regard to its dilution claim, the court concluded the Nader campaign’s use of MasterCard’s mark was “political in nature, not within a commercial context, and is therefore exempted from coverage by the Federal Trademark Dilution Act.” Again, noncommercial use did not trigger the statute (though this time it was because the ad was political, not because it was a parody).

The answer’s probably sitting there in McCarthy on Trademarks, but if a use that’s deemed noncommercial does not trigger the dilution portion of the Lanham Act, why does it trigger the infringement portion of the Lanham Act?

I realize the dilution portion of the statute expressly excepts parodic and noncommercial use — and infringement finds its roots in common law —but if my use of a trademark is deemed to be noncommercial, why do I have to go through likelihood of confusion analysis to determine if such use nonetheless infringes a trademark owner’s rights? Seems like a finding that my use is noncommercial would be the same “Get Out of Jail Free” card for infringement that it is for dilution.

Anyone willing to tell me why it’s not?