Protectable trade dress? Not even close, the Ninth Circuit finds

Protectable trade dress? Not even close, the Ninth Circuit finds

It doesn’t happen terribly often.

In fact, I don’t think it happens nearly enough. Awarding the prevailing party attorney’s fees in a trademark case, that is.

But that’s what happened in Secalt S.A. v. Wuxi Shenxi Const. Mach. Co., Ltd., 668 F.3d 677 (9th Cir. 2012), where plaintiffs claimed trade dress protection in their industrial-strength traction hoist.

Plaintiffs Secalt, S.A., and Tractel, Inc. (“Tractel”), argued the overall exterior appearance of their hoist is nonfunctional because the hoist’s design—wherein the component parts meet each other at right angles—provide a distinctive “cubist” look and feel.

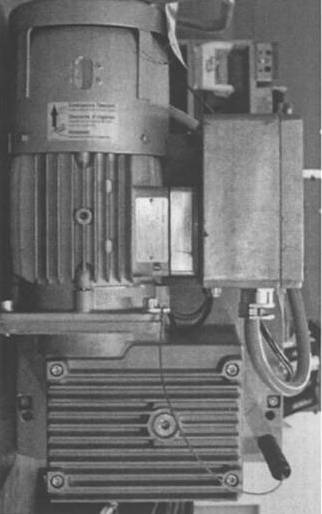

Tractel claimed its trade dress consisted of: “1) a cube-shaped gear box with horizontal fins; 2) a cylindrical motor mounted in an off-set position on the cube and partially overhanging the edge of the cube; 3) the cylindrical motor including vertical fins on a lower portion and a generally smooth sheet metal upper cover having a control descent lever and top cap positioned over the upper end and supported by rectangular legs; 4) a rectangular control box cantilevered to the motor by a square shaped member, the control box positioned over the cube, the control box including controls thereon; and 5) a rectangular frame.”

As evidence that these features aren’t functional, Tractel argued they were protected by a third party’s design patent.

The District of Nevada, however, didn’t buy the idea that the subject features weren’t functional. It granted summary judgment for the defendant and awarded attorney’s fees as an “exceptional” case.

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit found Tractel didn’t seem to understand that functional features can’t be protected under trade dress law simply because they are different than what the competition offers.

It wrote: “Tractel’s fundamental misunderstanding—which infects its entire argument—is that the presumption of functionality can be overcome on the basis that its product is visually distinguishable from competing products. While such distinctive appearance is necessary, it is here insufficient to warrant trade dress protection.”

It found that “[e]xcept for conclusory, self-serving statements, Tractel provides no other evidence of fanciful design or arbitrariness; instead, here, ‘the whole is nothing other than the assemblage of functional parts, and where even the arrangement and combination of the parts is designed to result in superior performance, it is semantic trickery to say that there is still some sort of separate ‘overall appearance’ which is non-functional.’”

Interestingly, the court did not find that Tractel acted in bad faith. Yet, the lack of bad faith didn’t save Tractel from an award of attorney’s fees.

“Although Tractel does not ultimately prevail, were it able to provide some legitimate evidence of nonfunctionality, this case would likely fall on the unexceptional side of the dividing line. When summary judgment motions were heard, the parties had been in discovery for almost two years, taken multiple depositions, and compiled substantial documents. Yet, Tractel could not identify the aesthetic value of the exterior design, and was reduced to arguing that it was pursuing a ‘cubist’ look and feel even though its own witnesses undercut this argument.”

The court concluded that “Tractel’s action appears to be a conscious, albeit misguided, attempt to assert trade dress rights in a non-protectable machine configuration.” On that ground, it affirmed the district court’s judgment and upheld the award of attorney’s fees to the tune of $836,899.99. (The court also upheld the district court’s finding that the rates defense counsel charged — $320 to $685 per hour in 2010 — were “reasonable.”)

Las Vegas Trademark Attorney’s discussion of its home-grown case here.