TTAB's Accelerated Case Resolution Procedures Probably Should Be Required

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Chief Judge David Sams writes in today’s INTA Bulletin (password required) about the availability of TTAB’s new Accelerated Case Resolution (ACR) procedures.

What is ACR? It’s the “TTAB initiative that provides parties to Board inter partes proceedings the opportunity to stipulate to final determination on the merits of cases at the pre-trial phase without the time or expense of a full trial.”

I’ve never taken advantage of ACR — at least I’ve never thought of it as ACR — but it sounds like a good deal. In my view, the regular TTAB procedure can be way too time-consuming and hence expensive.

Judge Sams suggests that “ACR is most suitable for cases in which the issues are relatively straightforward and the evidentiary record is not extensive. For example, an opposition or cancellation action brought on the grounds of priority and likelihood of confusion where priority is not at issue and the parties do not rely upon extensive testimony and documentary evidence would be an excellent candidate for accelerated case resolution.”

ACR can include: “Abbreviating the length of the discovery, testimony and briefing periods”; “Limiting the number and types of discovery and/or agreeing to limit the number of witnesses and/or streamline the method of introduction of evidence — for example, stipulating to facts and introduction of evidence by affidavit”; and “Permitting the TTAB to resolve issues of fact at summary judgment and treat the parties’ summary judgment motion papers and evidence as the final record and briefs on the merits of the case.”

That last idea — treating summary judgment evidence as the final record — is particularly attractive. I’ve gone through the wasteful trial period after the denial of cross-motions for summary judgment. No surprise: it felt wasteful.

Judge Sams says that parties can stipulate to ACR at any time before the trial phase, and may do so by telephone conference with the interlocutory attorney or by filing a stipulation.

The only problem in all of this is you need to get the opposing party’s agreement. It’d be a lot easier if TTAB rules required the parties to be efficient in their prosecution and defense. Leaving it up to agreement leaves room for mischief. That said, the availability of ACR is a nice step in the right direction.

Ninth Circuit Amends Opinion on Tribal Court Jurisdiction in Trademark Case

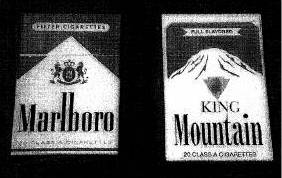

On June 11, the Ninth Circuit amended its January 20 opinion (STL discussion here) in the case of Philip Morris USA, Inc. v. King Mountain Tobacco Co., Inc. The question was whether colorable tribal court jurisdiction existed over a non-tribe member’s trademark claims against tribal defendants for alleged passing off of cigarettes on the Internet, on another tribe’s reservation, and elsewhere.

The Eastern District of Washington granted King Mountain’s motion for a stay, concluding there was a colorable claim to tribal court jurisdiction. In January, the Ninth Circuit reversed and remanded. In its amended decision, the court revised some of its reasoning but came to the same conclusion.

Perhaps the most notable change was in Judge William Fletcher’s concurrence criticising the majority’s opinion:

“The district court appears to have thought that sales both on and off the Yakama Reservation are at issue in this case. The district court noted in its order granting the stay that ‘Defendants began selling King Mountain cigarettes to smoke shops on the Yakama Reservation in January 2006’ and later began to make off-reservation sales. The district court concluded that because Philip Morris’s federal court suit made ‘claims against tribal members whose conduct occurred on reservation lands … there exists a colorable question of the existence of tribal court jurisdiction in this case over Philip Morris.’

“The panel majority makes clear, however, that sales by defendants of King Mountain cigarettes on the Yakama Reservation are not at issue. It writes, ‘Philip Morris’s complaint does not allege claims based on King Mountain’s sales of its cigarettes on the Yakama Reservation, although there are passing references to such sales in later pleadings.’ Because the only sales at issue took place off the Yakama Reservation, the question in this appeal is straightforward and quite narrow: Does the Yakama Tribal Court have colorable jurisdiction to decide whether off-reservation sales by tribal member defendants infringe the Marlboro trademark?

“The panel majority answers, correctly, that the tribal court does not have colorable jurisdiction. The answer is so clear that the majority could have written a simple opinion, or even an unpublished memorandum disposition, so holding. Instead, it has written an extended opinion containing a great deal of dicta. I respectfully decline to join the opinion, though I concur in the judgment.”

The case cite is Philip Morris USA, Inc. v. King Mountain Tobacco Co., Inc., No. 06-36066, __ F.3d __, No. 2009 WL 1622338 (9th Cir.) (June 11, 2009).

Licensee Lacks Standing to Claim Common Law Trademark Infringement

Plaintiff trademark licensee Beijing Tong Ren Tang USA Corp. doesn’t have standing to assert a claim for common law infringement, the Northern District of California found on June 2. Therefore, the court granted defendant TRT USA Corp.’s motion to dismiss.

“[T]he central issue appears to be whether California’s common law of trademarks, as distinct from the Lanham Act or California statutory trademark protection, allows a non-owner to bring suit for trademark infringement. To state a claim for infringement under California common law, a plaintiff must allege 1) its prior use of the trademark and 2) the likelihood of the infringing mark being confused with its mark. To show ‘prior use’ a plaintiff must demonstrate that they ‘first adopt[ed] or use[d] a trade name, either within or without the state,’ which is the requirement for ownership under the common law. Because Beijing TRT does not allege that it was the first to adopt or use the mark at issue, it may not bring suit for common law infringement under California law.”

The court noted its decision would have little practical effect on the case, as TRT USA did not dispute that Beijing Tong Ren Tang USA has standing to assert a Section 43(a) claim that makes similar allegations to its dismissed claim.

The case cite is Beijing Tong Ren Tang (USA) Corp. v. TRT USA Corp., No. 09-882, 2009 WL 1542651 (N.D. Cal.) (June 2, 2009).

As a Litigator, Judge Sotomayor Handled Many Trademark Matters

Judging by her answers on the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary’s Questionnaire for Judicial Nominees, Judge Sonia Sotomayor litigated an impressive amount of trademark issues. Here are some excerpts (with slight edits by STL):

- “I left the District Attorney’s office in 1984, and joined the firm of Pavia & Harcourt. My typical clients were significant European companies doing business in the United States. My practice at that firm focused on commercial litigation, much of which involved pre-trial and discovery proceedings for cases that were typically settled before trial. I appeared in numerous preliminary injunction hearings in trademark and copyright cases, and post-motion hearings before magistrate judges on a variety of issues.”

- “I represented the defendant Lozza SpA in this trademark infringement abandonment, unfair competition, breach of contract, and rescission action [Fratelli Lozza (USA) Inc. v. Lozza (USA) & Lozza SpA.] The plaintiff, a corporation owned and operated by a former shareholder of the defendant corporation, claimed the defendant had breached an agreement with the plaintiff for the trademark use of “Lozza” in the United States, had abandoned use of its marks in the United States, and had infringed certain of the plaintiff’s trademarks. I conducted the trial for the lead defendant, and secured a dismissal of all of the plaintiff’s claims. The Court also issued an injunction against the plaintiff’s use of the defendants’ marks, and of false and misleading terms in its advertising.”

- “From 1985, my former firm represented Fendi S.A.S. di Paola Fendi e Sorelle (“Fendi”) in Fendi’s national anticounterfeiting work. Frances B. Bernstein, a partner at Pavia & Harcourt (now deceased), and I created Fendi’s anticounterfeiting program. From 1988 until the time I left the firm for the bench in 1992, I was the partner in charge of that program. I handled almost all discovery work and substantive court appearances in cases involving Fendi. This work implicated a broad range of trademark issues including, but not limited to trademark and trade dress infringement, false designation of origin, and unfair competition claims.”

- “Approximately once every two months from 1989 to 1992, I, for Fendi, applied for provisional injunctive relief in district court to seize counterfeit goods from street vendors or retail stores. The applications required extensive submission of evidence documenting Fendi’s trademark rights, its protection of its marks, the nature of the investigation against the vendors, and Fendi’s right to ex parte injunctive relief. Generally, the street vendors defaulted but others appeared and settled pro se.”

- “The above-captioned cases involved a trial and a damages hearing on Fendi’s trademark claims against the defendants. In the first, the Burlington case, Fendi alleged that defendants knowingly trafficked in counterfeit goods and Fendi sought triple profits from the defendants and punitive damages. After extensive discovery, submission of a pre-trial order and memorandum, and Fendi’s presentation of its expert at trial, the case settled. I was sole counsel present at trial. In the Cosmetic World case, the Court granted Fendi’s summary judgment motion on liability and referred the matter to a magistrate judge for an inquest on damages. I conducted the contested hearing on damages before the magistrate judge who recommended an award in Fendi’s favor.”

Failure to Defend Can Lead to Default and Finding Infringement was Willful

As STL discussed here, 15 U.S.C. § 1117(c) was amended last fall to double to $2 million the range of statutory damages if a defendant’s counterfeiting is found to be “willful.” So what’s willful? A magistrate judge in the Eastern District of California recently addressed this question in recommending the court award Microsoft Corp. a default judgment against alleged counterfeiter John Marturano.

“Under the Lanham Act, infringement is willful, and thus triggers the enhanced statutory damages limit, if the defendant ‘had knowledge that its actions constitute an infringement.’ A defendant’s continued infringement after notice of his wrongdoing is probative of willfulness.

“Willfulness can also be inferred from a defendant’s failure to defend.”

Not that I’m complaining, but this gets a defaulted defendant two ways. First, the court awards the plaintiff a win because the defendant didn’t defend itself in the action. Then, the court can find the defendant’s failure to defend also supports a finding that the counterfeiting was willful. Seems a little like double-counting to me, but I guess a counterfeiter: (a) shouldn’t engage in counterfeiting, and (b) should defend itself in the litigation.

In applying this framework, the court not surprisingly found the defendant’s selling counterfeit MICROSOFT-branded goods was willful. However, it based its decision on the notice Microsoft sent the defendant rather than the defendant’s failure to defend himself in the case.

“Microsoft has submitted evidence that it sent a letter to Defendant in 2002 explaining that his activities were unlawful. Nevertheless, in 2006, Defendant subsequently continued to distribute infringing software, knowing such acts were unlawful. Therefore, the court finds that Defendant’s violations of the Copyright and Lanham Acts were willful.”

The case cite is Microsoft Corp. v. Marturano, No. 06-1747, 2009 WL 1530040 (E.D. Calif.) (May 27, 2009).