Entries in Fair Use (13)

Fair Use Doctrines Protect Lawful Use of Another's Trademark

The Pepsi Challenge: Made possible by comparative fair use

The Pepsi Challenge: Made possible by comparative fair use

We covered fair use today in my trademark class, and it occurred to me I haven’t talked about it much here.

Fair use, in all its flavors, is a defense to trademark infringement and a host of other forms of trademark wrongs. It’s the First Amendment winning out in the tension between freedom of speech and the right of a trademark owner to avoid infringement, dilution, cybersquatting, and unfair competition.

Here’s a quick review (or introduction) to the most recognized forms of fair use.

Classic Fair Use - Also known as “statutory fair use” since it’s codified in the Lanham Act, classic fair use is the descriptive use of words that happen to be someone else’s trademark. Just because someone uses it as a descriptive trademark doesn’t mean you can’t use it to accurately describe your good or service. For example, if true, I can say my coffee is both the best and is from Seattle notwithstanding the SEATTLE’S BEST COFFEE trademark.

Collateral Use - Use of a mark that does not claim sponsorship of goods. It’s ok to say that you’re selling reconditioned FORD trucks as long as you don’t suggest your refurbishments are factory authorized.

Comparative Use - Use of another’s trademark to identify the mark owner’s product in comparative advertising. As long as the comparison isn’t misleading, it’s perfectly ok to compare PEPSI to COKE.

Nominative Fair Use - Nominative fair use uses the plaintiff’s trademark to refer to plaintiff’s good or service. If there’s no other reasonable way to refer to the plaintiff’s good or service, it’s ok to use the plaintiff’s mark to do so as long as you don’t use more of the mark than is necessary and don’t imply any connection with the plaintiff. For example, it’s ok to say the SEATTLE SUPERSONICS, rather than “that professional basketball team that left town and hopefully will come back.”

Critique or Reporting Fair Use - Traditional First Amendment use is also carved out of the Lanham Act, so you report on, talk about, criticize, or parody any trademark by name. This is what allows Yelp to exist.

Remember, these are not immunities; they are defenses to violations of the Lanham Act. That means they’re something to invoke if accused of engaging in a trademark wrong. But they also carve out activity that is perfectly legal.

Commercial Pokes Fun at the NFL's Control of its "Super Bowl" Trademark

Screen shot from Samsung’s new commercial. It’s worth watching.

Screen shot from Samsung’s new commercial. It’s worth watching.

You can’t call it the Super Bowl.

Or that’s what the NFL would have you believe.

Really, that’s a joke. The game’s called the Super Bowl, and if you want to refer to the Super Bowl, you don’t have to call it the “Big Game.” Using a trademark owner’s trademark to refer to the owner’s branded good is perfectly fair use. Not that I expect the NFL to agree with me.

This video — a new Samsung commercial — makes great fun of the NFL’s over-reaching control of its trademark. It’s really worth a look.

Check it out now, before its screens during the Big Game.

Ways People Can Use Your Trademark without Your Permission

We’ve talked about what competitors can’t say about your trademark.

So what about ways competitors — and others — legally can use your trademark without your permission?

Here’s a quick list (again, not exhaustive):

- Comparative use. Pepsi famously put its cola to the test against Coca-Cola’s in the “Pepsi Challenge.” Your competitor likewise can use your trademark in trying to sell its goods or services — as long as it’s done so in a way that’s accurate. So, your competitor can say its product is cheaper. It lasts longer. It’s more effective. It can identify your product by name. It even can identify you by name. None of that is trademark infringement or false advertising as long as the comparison doesn’t make a false statement of fact or tend to mislead consumers.

- Descriptive use. If you use SPEEDY as a trademark in connection with oil change services, you’re going to have a hard time complaining about your competitor’s use of “quick,” “fast,” or even “speedy” to tout the competing services it provides. Your trademark does not give you monopoly rights over the word. Obviously, it doesn’t remove any words from the dictionary. If your competitor isn’t using the description as a trademark — in other words, if it only uses your mark as an accurate description of its services — it’s within its rights to do so. That’s one of the down-sides to your using a descriptive trademark.

- Collateral use. You’re Brand X. You make lawn mowers. I repair lawn mowers. I’m perfectly ok advertising the fact that I repair Brand X lawn mowers. I just can’t imply that you have approved me or that we have a relationship that doesn’t exist. That usually means I can use your name but not your logo, and only so much of your name as is needed to get my message across. You have no say in the matter, unless my use suggests you have authorized me as a provider of repairs or the like.

- Nominative use. If you’re the Rolling Stones (lucky you!), there’s only so many ways someone can describe you without using your name. The “British rock group consisting of Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Charlie Watts, and Ronnie Wood” doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue. Since it’s so much easier for me instead to refer to you as the “Rolling Stones,” I’m allowed to do so — even as part of a profit-making venture. My only limitation would be I can’t use any more of your mark (such as your logo) than is needed for me to do so. I’ll get in trouble if my use suggests an affiliation that doesn’t exist (like you approved my use). That would mean I can’t sell t-shirts with “Rolling Stones” in big letters, but I can organize and sell memberships in an unauthorized fan club.

- Parody and criticism. Your customer or former employee isn’t happy with you. If he or she wants to use your brand in a “sucks” or hater Web site saying how you’ve got a bad product or you’re a bad company, he or she can certainly do that. The information conveyed must be accurate, meaning he or she can’t say your product causes cancer if it doesn’t. But the First Amendment gives speakers broad rights to criticize. That includes making fun of your name or logo if it’s done in a way that clarifies the use doesn’t come from you and, instead, is criticizing or commenting about you.

The theme here is that fair use must be “fair.” If the use suggests an affiliation with the trademark owner, or that the owner has approved the message, that use isn’t fair (and is deceptive and illegal) if no such relationship actually exists. This is the intersection of trademark law and our constitutionally-protected right to free speech.

If Parody is Exempt from Dilution, Why isn't It Exempt from Infringement?

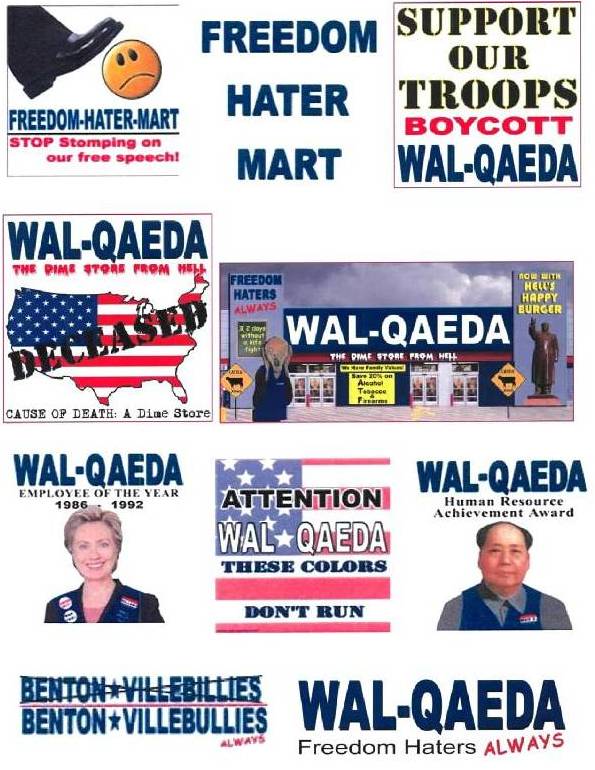

Not commerical, so no dilution: Charles Smith’s WAL-QAEDA parody

Not commerical, so no dilution: Charles Smith’s WAL-QAEDA parody

Discussing parody in my Advanced Trademark Law Seminar.

I’m stumped on one point.

In a number of cases involving the parodic use of a trademark, courts apply likelihood of confusion analysis to infringement claims. Successful parodies do not cause a likelihood of confusion, so they do not infringe trademark rights.

Analyzing dilution claims, however, courts in the same cases often treat parodies as noncommercial speech. For that reason, they conclude parodic uses are exempt from dilution claims.

In Smith v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 537 F.Supp.2d 1302 (N.D. Ga. 2008), for example, the court concluded Charles Smith’s use of WAL-QAEDA was not likely to confuse consumers with Wal-Mart’s trademarks, so Wal-Mart’s infringement claim against him could not stand. With respect to Wal-Mart’s dilution claim, the court found WAL-QAEDA succeeded as a parody because it communicated Mr. Smith’s negative feelings about Wal-Mart. “Thus, Smith’s parodic work is considered noncommercial speech and therefore not subject to Wal-Mart’s trademark dilution claims….” In other words, Mr. Smith’s parody did not trigger the dilution statute because it was noncommercial.

Similarly, in MasterCard Intern. Inc. v. Nader 2000 Primary Committee, Inc., 2004 WL 434404, *9 (S.D.N.Y.), the court found Ralph Nader’s use of MasterCard’s trademarks in a political ad that spoofed MasterCard’s “Priceless” advertising campaign was not likely to confuse consumers, so it dismissed MasterCard’s infringement claim. With regard to its dilution claim, the court concluded the Nader campaign’s use of MasterCard’s mark was “political in nature, not within a commercial context, and is therefore exempted from coverage by the Federal Trademark Dilution Act.” Again, noncommercial use did not trigger the statute (though this time it was because the ad was political, not because it was a parody).

The answer’s probably sitting there in McCarthy on Trademarks, but if a use that’s deemed noncommercial does not trigger the dilution portion of the Lanham Act, why does it trigger the infringement portion of the Lanham Act?

I realize the dilution portion of the statute expressly excepts parodic and noncommercial use — and infringement finds its roots in common law —but if my use of a trademark is deemed to be noncommercial, why do I have to go through likelihood of confusion analysis to determine if such use nonetheless infringes a trademark owner’s rights? Seems like a finding that my use is noncommercial would be the same “Get Out of Jail Free” card for infringement that it is for dilution.

Anyone willing to tell me why it’s not?

Delicious Trademark Dispute Not Appropriate for Summary Judgment

Trademark disputes aren’t usually appropriate for being decided on summary judgment.

That’s what the Ninth Circuit reiterated last week in Fortune Dynamic, Inc. v. Victoria’s Secret Stores Brand Management, Inc.

In that case, Victoria’s Secret sold or gave away hot pink tank tops with the word “Delicious” printed across the front. The purpose of its efforts was to promote its BEAUTY RUSH beauty products.

In that case, Victoria’s Secret sold or gave away hot pink tank tops with the word “Delicious” printed across the front. The purpose of its efforts was to promote its BEAUTY RUSH beauty products.

Fortune Dynamic sued, alleging that Victoria’s Secret’s use infringed its incontestable registration for DELICIOUS for footwear.

As the Ninth Circuit later summarized, “Victoria’s Secret executives offered two explanations for using the word ‘Delicious’ on the tank top. First, they suggested that it accurately described the taste of the BEAUTY RUSH lip glosses and the smell of the BEAUTY RUSH body care. Second, they thought that the word served as a ‘playful self-descriptor,’ as if the woman wearing the top is saying, ‘I’m delicious.’”

The Central District of California granted summary judgment in Victoria’s Secret’s favor.

Fortune Dynamic appealed to the Ninth Circuit.

The Ninth Circuit reversed and remanded, finding that it was not appropriate for the district court to decide that no likelihood of confusion existed and that the fair use doctrine applied as a matter of law.

“This case is yet another example of the wisdom of the well-established principle that ‘[b]ecause of the intensely factual nature of trademark disputes, summary judgment is generally disfavored in the trademark arena,’” the court said. “We are far from certain that consumers were likely to be confused as to the source of Victoria’s Secret’s pink tank top, but we are confident that the question is close enough that it should be answered as a matter of fact by a jury, not as a matter of law by a court.

“The same is true of Victoria’s Secret’s reliance on the Lanham Act’s fair use defense. Although it is possible that Victoria’s Secret used the term ‘Delicious’ fairly — that is, in its ‘primary, descriptive sense’ — we think that a jury is better positioned to make that determination.”

The case cite is Fortune Dynamic, Inc. v. Victoria’s Secret Stores Brand Management, Inc., __ F.3d __, 2010 WL 3258703, No. 08-56291 (9th Cir. Aug. 19, 2010).

Photo credit: Borrowed from The Briefcase: Commentary and Analysis of Ohio Law