Overcoming a Descriptiveness Objection to Federal Trademark Registration

What’s a trademark owner to do if the PTO denies an application for federal trademark registration because it finds the mark is “merely descriptive”?

A mark is merely descrptive under U.S. trademark law if it immediately conveys information about the good or service being sold in connection with the mark. In such cases, the mark does not function as a trademark because it only tells consumers about what’s being sold, rather than who is selling it. The latter message is what a trademark needs to convey.

That means descriptive brand names like SPEEDY AUTO GLASS and SEATTLE’S BEST COFFEE are not registrable on the PTO’s Principal Register — that is, until they achieve “secondary meaning.” Secondary meaning occurs when the mark has become linked in consumers’ minds with the trademark owner, rather than the trademark owner’s goods. In other words, the primary, descriptive message has been subverted by the secondary meaning that identifies the source of the goods or services.

Proving secondary meaning is what’s needed to overcome the PTO’s objection. This is first shown through longstanding use. The statute sets the usual minimum benchmark at five years, but the PTO often requires more evidence of secondary meaning than that. Even ten or fifteen years’ use may not be enough.

So what else proves secondary meaning? Evidence of what one might expect to indicate that consumers have come to associate the brand with the owner: dollar sales under the mark, advertising figures, samples of advertising, and consumer or dealer statements that the mark is recognized as referring to the trademark owner. Generally, the most persuasive evidence shows the owner’s longstanding use of the mark, lots of money spent on advertising, and lots of sales made. This includes evidence of advertising on TV, radio, in print, on the web, and any other evidence that shows that consumers understand descriptive marks like SPEEDY AUTO GLASS and SEATTLE’S BEST COFFEE point to a specific source, rather than a description of goods or services.

If an owner doesn’t have this evidence, or the PTO finds the offered evidence isn’t enough, the owner can still obtain registration by amending its application for registration on the Supplemental Register. Doing so loses the benefits of registration on the Principal Register — including the presumption that the owner is the exclusive nationwide user of the mark in connection with the specified goods or services — but it still entitles the owner to use the Circle-R symbol that indicates its mark is registered. It’s not a result an applicant generally hopes for, but it is better than nothing.

Foreign Trademark Owners May Have No Trademark Rights Here

Foreign owners may not have any trademark rights in the United States.

Despite treaty provisions that say otherwise, U.S. courts generally do not recognize foreign trademark rights in the States — no matter how well-known those marks might be abroad. That means someone in the U.S. can copy your mark, imitate your business, and open up shop under your name. If you haven’t made sales here, the imposter probably would be within its rights. Incredibly enough, the imposter could even block you from later making sales here under your mark. Because it made sales here first, its rights probably would be superior to yours.

There are two main solutions. First, if you have a foreign registration, you can leverage it into getting a U.S. registration. That would give you immediate rights in the States, even if you haven’t used the mark yet in the States. You just need a bona fide intent to use the mark here.

Second, you should start making sales to U.S. customers. That would give you automatic rights in the geographic markets in which you sell. Anyway, sales in the States are needed to maintain a U.S. registration that is based on a foreign registration.

In the end, without a U.S. presence, foreign owners should not expect that their foreign trademark rights will be given much leeway here.

"Charbucks" Case Illustrates the Power and Limits of Trademark Dilution

Trademark dilution is a creature of statute.

As incorporated in the federal Lanham Act, it prohibits a later-adopter from using a trademark that is likely to dilute the earlier-adopter’s famous trademark. It doesn’t matter if the later use is likely to cause confusion — the standard for trademark infringement. What matters is the probability of whether the famous mark’s power to distinguish its owner’s goods and services from those of others has been “diluted,” or whittled away. This is called dilution by “blurring.” The statute also prohibits another form of dilution — a likelihood of dilution by “tarnishment,” or a lessening of the brand’s good reputation.

Because trademark dilution doesn’t require an owner to show likelihood of confusion — and, therefore, provides super-trademark rights — the federal statute limits such protection to the owners of truly “famous” trademarks, which the statute defines as trademarks that are widely known on a nationwide basis. In other words, the dilution cause of action is only available to the owners of household names.

STARBUCKS is clearly one such name. Therefore, Starbucks Corp. was able to avail itself of the dilution cause of action against coffee roaster Wolfe’s Borough Coffee, Inc., d/b/a Black Bear Micro Roastery, which had named some of its coffee CHARBUCKS BLEND and MISTER CHARBUCKS. Starbucks argued the roaster’s doing so was intended to and did call to mind Starbucks’ famous STARBUCKS brand, so Starbucks was entitled to an injunction stopping such use.

After much wrangling, Starbucks appears to have finally lost. The case went up and down to the Second Circuit several times, and in the middle of the litigation, the statute was re-written. But in the end, the Second Circuit found that despite having super-trademark rights, Starbucks did not prove the roaster’s marks were likely to dilute the famous STARBUCKS brand.

In making that decision, the Second Circuit weighed the factors set forth in the statute. It found the district court was not wrong when it concluded the parties’ marks were not very similar. It also found the district court was not wrong to conclude that Starbucks’ consumer survey was flawed because it did not reflect how the parties’ marks were used in the marketplace. Therefore, it found the survey “only minimally” proved that consumers actually associated the roasters’ marks with STARBUCKS.

The court found three of the statutory factors — distinctiveness, recognition, and exclusivity — favored Starbucks, but “the more important factors in the context of this case are the similarity of the marks and actual association.”

This led the Second Circuit to conclude: “Ultimately what tips the balance in this case is that Starbucks bore the burden of showing that it was entitled to injunctive relief on this record. Because Starbucks’ principal evidence of association, the Mitofsky survey, was fundamentally flawed, and because there was minimal similarity between the marks at issue, we agree with the District Court that Starbucks failed to show that Black Bear’s use of its Charbucks Marks in commerce is likely to dilute the Starbucks Marks.”

This goes to show that while potentially powerful — really powerful — the federal dilution statute does have its limits.

When to Use the Circle-R Symbol and When to Use "Inc."

A client that obtained a federal trademark registration recently asked me a good, but basic question.

Now that I’m registered, when do I use the Circle-R symbol (®)? And when do I use “Inc.”?

Once a registration issues, the trademark owner should stop using the TM symbol if it has previously made such use and replace it with the Circle-R symbol. “TM” indicates the owner claims rights in the words or symbol that precedes the mark. The Circle-R symbol conveys the same message, except it indicates that the mark is registered. Both symbols warn would-be copycats to steer clear of the owner’s mark when adopting their own trademark. The message is that if they choose a mark that creates a likelihood of confusion with the owner’s prior mark, the prior owner will do what’s needed to protect its legal rights.

Both of those symbols focus on the owner’s trademark or brand name. That’s the device the owner uses to tell consumers that the good or service sold in connection with the brand comes from them.

That’s often the same as the business’ name, but the context is different. When referring to the formal business name (such as in a contract or when opening a checking account), one should refer to the appropriate corporate form. In other words, that’s when the owner should use “Inc.,” “Corp.,” “LLC,” or other abbreviation that is part of the company’s formal name.

To summarize, when communicating with consumers to indicate that goods or services come from you, use “TM” (an optional, but helpful symbol if the mark is not registered) or the Circle-R symbol (if the mark is federally registered). When referring to the company itself (often when communicating with other entities or employees), use the formal company name, which may include “Inc.,” “Corp.,” “LLC,” or the like.

Political Candidate Borrows Colors and Logo of Beloved Soccer Team

There’s an election today here in Buenos Aires. To an American, this is interesting for several reasons. First, the election is held on a Sunday, so everyone can vote. Second, voting is mandatory. Third, you can’t buy booze today, in order to promote clear decision-making. Granted, I was a poly-sci major in college, but I find these election-day differences fascinating.

There’s an election today here in Buenos Aires. To an American, this is interesting for several reasons. First, the election is held on a Sunday, so everyone can vote. Second, voting is mandatory. Third, you can’t buy booze today, in order to promote clear decision-making. Granted, I was a poly-sci major in college, but I find these election-day differences fascinating.

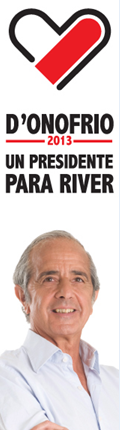

There are some differences on the trademark front as well. I came across an ad for Rodolfo D’Onofrio, a candidate who hales from River Plate, a well-to-do part of Buenos Aires. River Plate is also home of Club Atlético River Plate, a beloved local soccer team. What’s strange is he adopts the red-sash design used by the soccer team (“A president for River”). Even to a foreigner like me, his reference to the team is obvious. Now, it’s possible the red-sash design refers to the neighborhood, which the soccer team has borrowed, but the team is so well-loved in parts here that I have a hard time believing Sr. D’Onofrio isn’t seeking to enshroud himself in the team’s goodwill.

There are some differences on the trademark front as well. I came across an ad for Rodolfo D’Onofrio, a candidate who hales from River Plate, a well-to-do part of Buenos Aires. River Plate is also home of Club Atlético River Plate, a beloved local soccer team. What’s strange is he adopts the red-sash design used by the soccer team (“A president for River”). Even to a foreigner like me, his reference to the team is obvious. Now, it’s possible the red-sash design refers to the neighborhood, which the soccer team has borrowed, but the team is so well-loved in parts here that I have a hard time believing Sr. D’Onofrio isn’t seeking to enshroud himself in the team’s goodwill.

Can you imagine a political candidate in the States borrowing Yankee pinstripes, colors, and old-timey lettering in an ad that says he’s New York’s candidate?

Sr. D’Onofrio’s ad (above left), Club Atlético River Plate’s logo (above right), and the outside of River Plate’s stadium before a match (above center).

(Photo by STL.)