Chrysler's Ad Tells Consumers Its JEEP SUVs Are Special, Not Generic

My reading isn’t exactly up to date. Yesterday I came across this ad in the Sept. 17, 2007, issue of The New Yorker. The text reads:

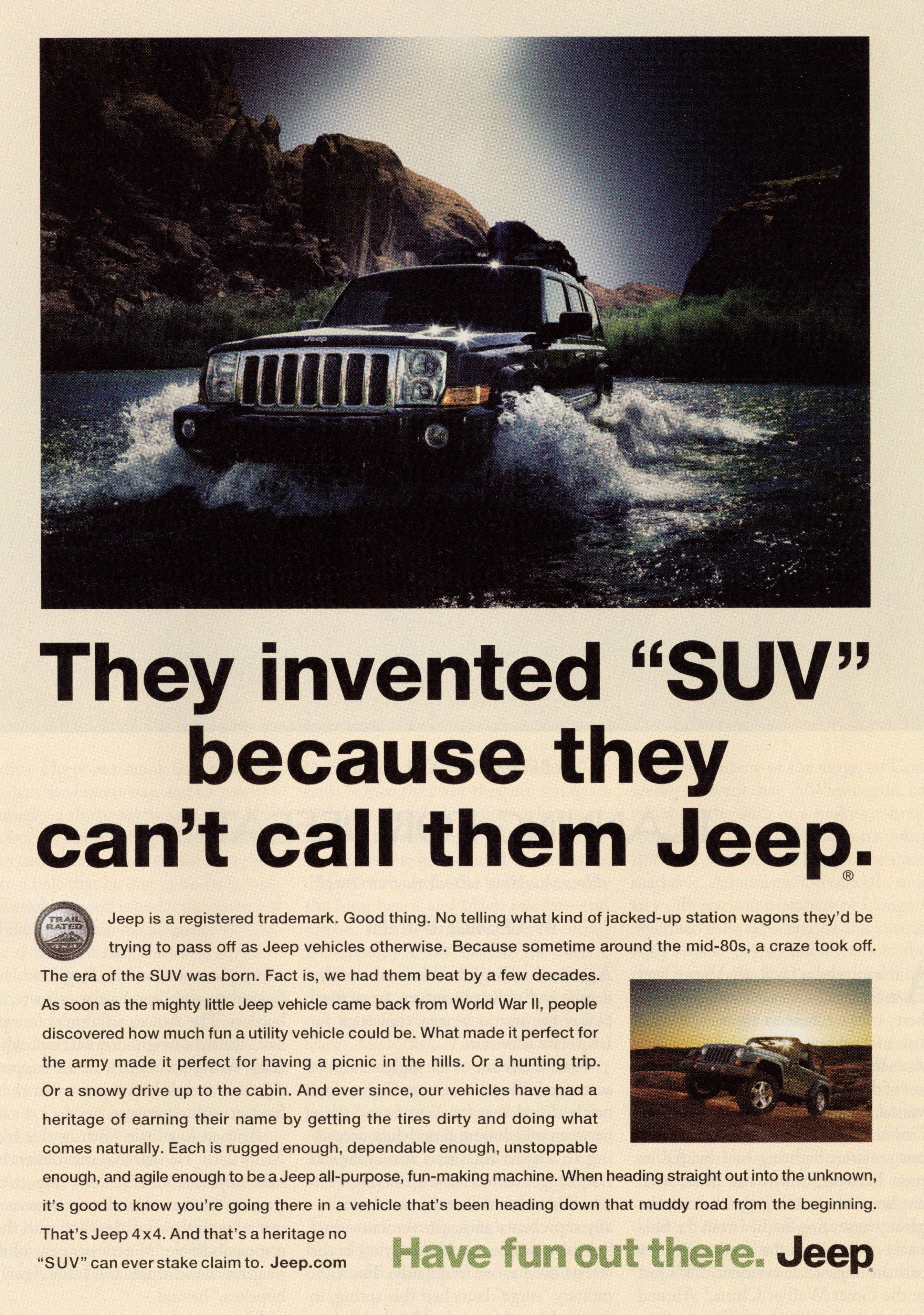

“They invented ‘SUV’ because they can’t call them Jeep®.

“Jeep is a registered trademark. Good thing. No telling what kind of jacked-up station wagons they’d be trying to pass off as Jeep vehicles otherwise. Because sometime around the mid-80s, a craze took off. The era of the SUV was born. Fact is, we had them beat by a few decades. As soon as the mighty little Jeep vehicle came back from World War II, people discovered how much fun a utility vehicle could be. What made it perfect for the army made it perfect for having a picnic in the hills. Or a hunting trip. Or a snowy drive up to the cabin. And ever since, our vehicles have had a heritage of earning their name by getting the tires dirty and doing what comes naturally. Each is rugged enough, dependable enough, unstoppale enough, and agile enough to be a Jeep all-purpose, fun-making machine. When heading straight out into the unknown, it’s good to know you’re going there in a vehicle that’s been heading down that muddy road from the beginning. That’s Jeep 4x4. And that’s a heritage no ‘SUV’ can ever stake claim to.”

It’s interesting when companies use scarce advertising dollars to tell consumers not only to buy their products, but also to use their trademarks in the proper way. (See other STL posts on this subject from June 5, 2007 and Oct. 25, 2007.)

This ad does both quite well: “SUV is generic and not special. JEEP is not one of those ordinary SUVs. It denotes a special type of SUV, the original SUV, the one we make. It’s a difference worth taking note of. A difference worth paying for.”

Now, in the year since this ad was published, gas prices have spiked above $4 per gallon and SUVs have fallen out of favor. Chrysler, LLC, has bigger things to worry about than its well-known trademark becoming generic.

It remains to be seen whether Chrysler can address those bigger problems as effectively as I think it addresses this one.

Ninth Circuit Finds Contempt Order Not Immediately Appealable

On Aug. 20, the Ninth Circuit decided Koninklijke Philips Electronics, N.V. v. KXD Technology, Inc., involving the appealability of a contempt order stemming from the violation of a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction.

The District of Nevada granted the plaintiff injunctive relief enjoining the defendants from selling any product that infringed the plaintiff’s registered trademarks. The court also ordered the defendants to file a report setting forth their inventory of counterfeit goods and another report detailing how they have complied with the preliminary injunction.

Within the next year, it became clear to the district court that the defendants had no intention of complying with those orders. The defendants filed no reports, even after the plaintiff moved for sanctions.

In response, the court granted plaintiff’s motion, holding the defendants jointly and severally liable to the plaintiff for $353,611.70 in attorney’s fees, $37,098.14 in seizure and storage costs, $1,284,090.00 in lost royalties, and $10,000 per day until the reports were filed beginning 14 days after the order was entered.

The defendants appealed these sanctions to the Ninth Circuit. The plaintiff argued that such an interlocutory appeal was impermissible and the Ninth Circuit lacked jurisdiction to hear it.

The court first considered whether the contempt order was civil or criminal. If civil, the court had no jurisdiction until the decision became part of a final judgment. If criminal, however, the court had immediate jurisdiction because criminal contempt orders are appealable when entered.

The court noted the “distinction between the two forms of contempt lies in the intended effect of the punishment imposed. The purpose of civil contempt is coercive or compensatory, whereas the purpose of criminal contempt is punitive.”

The court found the contempt order was civil and, therefore, not immediately appealable.

“The attorney’s fees, lost royalties, and storage costs were assessed in order to compensate the plaintiff for losses sustained. Furthermore, the per diem fine was not to be assessed until fourteen days after the entry of the order, and the defendants could avoid paying the fine by complying with the terms of the injunction. Because the per diem fine allowed the defendants the opportunity to purge the contempt before payment became due, it was a civil sanction.”

The court also found on policy grounds that “holding that a civil sanction is directly appealable if it is immediately payable risks eviscerating the fundamental rule that compensatory sanctions are civil and not appealable on interlocutory review. Further, we note that defendants will have the opportunity to appeal the sanctions imposed after a final judgment. In sum, we are not persuaded that the defendants face irreparable harm and, in any event, find that, because of the defendants’ conduct, any risk of harm is appropriately placed upon them.”

The case cite is Koninklijke Philips Electronics, N.V. v. KXD Technology, Inc., __ F.3d __, 2008 WL 3852719, No. 07-15310 (9th Cir. Aug. 20, 2008).

Microsoft Settles with Alleged Australian Cybersquatters

In April, Microsoft Corp. sued Trellian Pty. Ltd. of Australia and other defendants in King County Superior Court for cybersquatting, trademark infringement, false designation of origin, and other trademark claims related to the defendants’ alleged registration of domain names that are identical or confusingly similar to Microsoft’s trademarks.

In April, Microsoft Corp. sued Trellian Pty. Ltd. of Australia and other defendants in King County Superior Court for cybersquatting, trademark infringement, false designation of origin, and other trademark claims related to the defendants’ alleged registration of domain names that are identical or confusingly similar to Microsoft’s trademarks.

As a side note, you don’t see many Lanham Act claims brought in state court, though it’s perfectly appropriate to bring such claims there.

Despite concurrent jurisdiction, the claims didn’t stay in state court long. Defendants removed the case to the Western District.

In July, defendants largely denied plaintiff’s allegations.

The parties have now buried the hatchet. Today, Microsoft filed a Notice of Settlement asking the court to strike all deadlines in the case and advising it expects to have a formal settlement agreement signed and the case dismissed within 30 days.

The case cite is Microsoft Corp. v. Trellian Pty. Ltd., No. 08-776 (W.D. Wash.).

Beware of Official Looking Trademark Monitoring Services

I’ve written about deceptive pitches to trademark applicants and registrants in the past. I came across another one today. Or, rather, my client did.

My client, a small business owner, has a few pending applications that have just cleared examination and are about to be published.

Last week, he received an official-looking form in the mail from an official-sounding outfit regarding its “Trademark Monitoring and Notification Service.” The form has his company’s name and address, the serial number and filing date of his applications, and citations to the United States Code. It also lists a Washington, D.C., return address and has “United States” as part of its name.

The form says the sender “provides a trademark owner with information that may be important to maintain its own trademark rights and can allow a trademark owner the ability to oppose marks before these marks become registered. Trademark monitoring is an annual subscription and commences upon receipt of the form below with due payment.”

The company charges $385 per trademark per year for these services.

Trademark watch services can be valuable, but there’s no reason why an applicant whose mark has not yet been published for opposition would need such services.

The statement at the bottom says it all: the service “…IS AN ELECTIVE SERVICE AND IS NOT A LEGAL REQUIREMENT OR A MANDATORY REGISTRATION.”

Judging by my clients’ continued questions about notices like this, the disclaimer doesn’t seem to be doing its job.

Companies like this may provide a legitimate service. But from where I sit, it only looks like they’re trying to profit from trademark owners’ inexperience.

Watch out for them. The letter looks official, but it’s really just an official waste of money.

Trafficking in Counterfeit Labels Renders Alien Inadmissible to Stay in United States

On Aug. 6, the Ninth Circuit concluded that willingly trafficking in counterfeit goods constitutes “inherently fraudulent” conduct that renders an alien ineligible for a visa to remain in the United States.

Mr. Hung Lin Wu, a 45-year-old permanent resident of the United States and citizen of Taiwan, pleaded guilty to trafficking in counterfeit labels. The U.S. Board of Immigration Appeals found this was a crime involving moral turpitude and, therefore, that Mr. Wu was ineligible to remain here.

Mr .Wu appealed.

The Ninth Circuit denied his petition.

In particular, the Ninth Circuit found that pleading guilty to “knowingly [trafficking] in a counterfeit label affixed or designed to be affixed to” a specified set of materials is “categorically a plea to an inherently fraudulent crime because the statute of conviction’s elements fit within the definition of inherently fraudulent conduct, which is knowingly making false representations in order to gain something of value.”

“First, counterfeit labels are by definition false representations because they ‘appear[] to be genuine, but [are] not.’ Persons who traffic in such materials knowing them to be counterfeit perpetuate the false representation, as they are knowingly passing off counterfeit material as real. Second, according to [18 U.S.C.] § 2318, the term ‘traffic’ means ‘to transport … as consideration for anything of value.’ Therefore, the act of trafficking is done necessarily ‘to gain something of value.’”

By this reasoning, and under the Ninth Circuit’s recent decision in Tall v. Mukasey (STL post here), the court found that Mr. Wu had committed a crime of moral turpitude, rendering him inadmissible to live here.

The case cite Wu v. Mukasey, 2008 WL 3166511 (9th Cir. Aug. 8, 2008).