No Judgment as a Matter of Law in Baden v. Molten False Advertising Case

STL readers may remember the patent infringement and false advertising case of Baden Sports, Inc. v. Kabushiki Kaisha Molten and Molten U.S.A., Inc., that went to trial in the Western District last August. The jury awarded Baden more than $8 million to compensate it for Molten’s intentionally falsely advertising that its basketballs were “innovative technology that is proprietary to Molten.” (STL’s posts on the case here, here and here.)

Following the jury’s verdict, Molten moved for judgment as a matter of law on the ground that Baden’s false advertising claim as presented to the jury should be vacated because the claim is barred by the Supreme Court’s decision in Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 539 U.S. 23 (2003).

On Jan. 28, Judge Marsha Pechman denied the motion. Explaining the decision, the court stated: “Dastar held that a false advertising claim under § 43 of the Lanham Act cannot be based on inventorship or ownership of a product. In its order granting in part and denying in part Molten’s motion for summary judgment on Baden’s Lanham Act claims, the Court concluded that Dastar does not bar Plaintiff’s false advertising claim based on Molten’s advertising that its product or technology is ‘innovative’ because ‘whether something is ‘innovative’ does not turn on who owns or offers a product.’ ‘[A]ny advertising indicating that Molten’s ‘Dual Cushion Technology’ is ‘innovative’ or new relates, not to the inventor of Molten’s basketball technology, but to the ‘nature, characteristics, [or] qualities’ of the basketballs themselves.’ Molten argues that despite the Court’s ruling, Baden presented evidence at trial that confirms that its Lanham Act claim is merely an inventorship claim, i.e., a claim that Molten falsely advertised its dual cushion technology as its own, rather than Baden’s invention.”

“The Court instructed the jury regarding Baden’s Lanham Act claim in a series of instructions. In its ‘Unfair Competition’ instruction, the Court explained that ‘Baden Sports claims Molten Corp. and Molten USA advertised their ‘dual cushion’ basketballs as a Molten innovation and they were not. The Court also instructed that to prevail on their false advertising claim, Baden must prove that ‘in advertisements, defendants made false statements of fact about their own product….”

“Several witnesses testified that Molten falsely advertised its ‘dual cushion technology’ as a Molten innovation. Although some of that testimony indicates that the witnesses believed that Molten’s advertising was false because Baden actually created the patented design, not Molten, other testimony makes clear that the witnesses believed the advertising was false because Molten’s product was not ‘new.’ The fact that witnesses used Baden’s prior design as evidence to show that Molten’s product was not innovative or new does not mean that Baden was actually basing its false advertising claim on the allegation that ‘Molten didn’t make it, we did.’ The Court concludes that Baden’s false advertising claim, as presented to the jury, does not run afoul of Dastar.”

The case cite is Baden Sports, Inc. v. Kabushiki Kaisha Molten, 2008 WL 238593, No. 06-210 (W.D. Wash. Jan. 28, 2008).

No Temporary Restraining Order Enjoining Use of COMMON SENSE

When things are slow in Seattle…

…STL reports on trademark issues elsewhere. That’s what I’ve been doing for the last couple of days.

Here’s a new trademark decision from the Northern District of California. Plaintiff Common Sense Media, Inc., applied for a temporary restraining order against defendant Common Sense Issues, Inc., based on plaintiff’s allegations that defendant is infringing its registered trademarks, COMMON SENSE MEDIA and COMMON SENSE MEDIA and Design. In particular, plaintiff asked the court to temporarily restrain defendant from using its COMMON SENSE ISSUES mark or any similar designation.

On Jan. 25, Judge Claudia Wilken denied plaintiff’s application. She found that “CSM has not made a sufficient showing of likely success on the merits of its claims and of the immediate threat of irreparable harm to justify granting the relief it seeks. Although ‘Common Sense Issues’ is similar to CSM’s trademarks, the phrase, ‘common sense’ is not unique, and the field of registered trademarks including the phrase is crowded. Many of these marks consist of the phrase, ‘common sense’ followed by a generic descriptive word similar to the word, ‘issues.’”

The court also found “it does not appear that the services provided by CSM and CSI are so closely related that the public would reasonably believe they come from the same source. CSM is a nonpartisan organization that provides information services related to children and the media. CSI is a political action group that provides voters with information on the positions of presidential candidates with respect to particular issues. While CSM argues that nothing would prevent CSI in the future from providing information on issues related to children and the media, this possibility cannot serve as the basis for a present claim of trademark infringement.”

Finally, the court concluded plaintiff had not shown it would suffer irreparable harm if the requested temporary restraining order did not issue.

The case cite is Common Sense Media, Inc. v. Common Sense Issues, Inc., 2008 WL 220120, No. 08-0155 (N.D. Calif.).

Wrestler "Warrior" Avoids Game Maker's Motion to Dismiss Trademark Claims

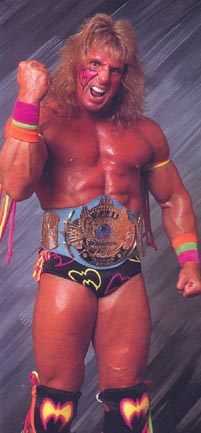

Ultimate Creations, Inc., the licensing company owned by former professional wrestler Warrior (his legal name) brought suit in the District of Arizona against video game maker THQ Inc. over video games that use Ultimate’s WARRIOR registered trademark and and trade dress in the wrestler’s costume and image. THQ moved for summary judgment on grounds of fair use and the protectability of Ultimate’s unregistered trade dress. On Jan. 24, Judge Stephen McNamee found in Ultimate’s favor.

The court summarized the facts as follows:

“Warrior claims that his wrestling character was distinctive because he had long, flowing hair, wore arm pads and knee pads with a fringe, displayed on his costume and face a logo roughly in the shape of an upside-down ‘W’ — the logo, originated from ‘Parts Unknown,’ had an exceptionally muscular build, and used ‘signature’ moves in his wrestling performances.

“Warrior claims that his wrestling character was distinctive because he had long, flowing hair, wore arm pads and knee pads with a fringe, displayed on his costume and face a logo roughly in the shape of an upside-down ‘W’ — the logo, originated from ‘Parts Unknown,’ had an exceptionally muscular build, and used ‘signature’ moves in his wrestling performances.

“In 2003, the parties entered into negotiations to license intellectual property associated with Warrior. The draft license agreement included the use of Warrior’s ‘name, voice, facsimile signature, nickname, likeness, signature moves, entrance music, endorsement, right of publicity, and biographical sketch as it may appear in photographs, film, video clips, etc.’ However, the negotiations eventually terminated without entering into a contract.”

In the lawsuit, “Plaintiff alleges that Defendant began to use the likeness, moves, trade dress, marks, and other intellectual property associated with Warrior in its video game as early as October of 2003. Specifically, players may use the [Create-A-Wrestler] feature on the games to create a character that has a similar build, face paint, and logo symbol as Warrior, that uses the entrance and finishing moves found under the label ‘OUW’ that are similar to Warrior’s, that has the call name ‘The Warrior’ or ‘Warrior,’ and is from ‘Parts Unknown.’ Plaintiff contends that this feature causes confusion as to whether Plaintiff sponsored or is associated with the game.”

On THQ’s fair use defense, the court concluded: “Defendant argues that it used the name ‘Warrior’ descriptively and not as a mark, and thus its use was fair. Despite this assertion, the Court finds that a jury could find that neither the mark nor the similar symbol was used in good faith based on the prior, unsuccessful negotiations between the parties. What is clear is that the use of the name Warrior was not necessary to create or market the video games. Also, the combination of signature moves, the face paint, the similar symbol and ‘Warrior’ call name suggests that Defendant intentionally provided the tools for consumers to create a wrestler in the likeness of Warrior without regard to his intellectual property rights. Thus, a jury could conclude that Defendant’s use was an improper attempt to capitalize on the popularity of the Warrior wrestling character. As such, summary judgment on Plaintiff’s claim of infringement of registered trademarks and service marks is not proper.”

As for Ultimate’s trade dress claim, the court found: “Warrior’s trade dress involves the costume, symbol, face paint, and color combinations that make up the overall image of his wrestling character. Through the video games, Defendant has made these elements available to its consumers. The websites where players exchange information regarding how to create the Warrior wrestling character suggest that Warrior has a distinctive trade dress, which supports a finding of secondary meaning in Warrior’s overall appearance, and denotes possible confusion as to whether the video games are affiliated with Warrior himself. The elements of trade dress also appear to be non-functional, and the combination of the elements may be sufficient to create a distinctive trade dress that is capable of protection. Thus, taken as a whole, a reasonable person could find that Defendant has committed a violation of Plaintiff’s unregistered trademarks or trade dress under Section 43(a) by confusing consumers as to Plaintiff’s affiliation, connection, or association with Defendant’s games.”

The case cite is Ultimate Creations, Inc. v. THQ Inc., 2008 WL 215827, No. 05-1134 (D. Ariz. Jan. 24, 2008).

United States Olympic Committee Doesn't Sue "Olympic" Businesses Very Often

A reporter recently asked me how often the United States Olympic Committee has sued the owner of an “Olympic”-named business in Washington. The answer? In the Western District of Washington, where I would expect such a suit to be brought: never. At least not since 1991, according to the federal courts’ U.S. Party/Case Index, which I checked out this afternoon.

A reporter recently asked me how often the United States Olympic Committee has sued the owner of an “Olympic”-named business in Washington. The answer? In the Western District of Washington, where I would expect such a suit to be brought: never. At least not since 1991, according to the federal courts’ U.S. Party/Case Index, which I checked out this afternoon.

Turns out as heavy-handed as the USOC seems to be lately in this state full of businesses named “Olympic” in honor of our Olympic Mountains, the USOC has taken a light touch when it comes to filing suit.

The same appears true around the country. Since 1991, it looks like the USOC has brought only 25 lawsuits identified by PACER as being “trademark” lawsuits, with only six suit against defendants with “Olympic” in their name. These include:

- USOC v. Olympic Spa Covers Inc., No. 04-01096 (C.D. Calif);

- USOC v. Olympic Carrier Corp., No. 02-00880 (N.D. Georgia);

- USOC v. Olympic Protective Services, Inc., No. 01-01002 (N.D. Calif.);

- USOC v. Bouzounis, d/b/a Olympic Incentive Ideas Inc., No. 91-00526 (S.D. Ohio);

- USOC v. Olympic Diamond Corp., No. 91-00532 (E.D.N.Y); and

- USOC v. Galaxy Cafe, d/b/a Olympic Cafe, No. 93-00288 (S.D. Georgia).

Of the six suits the USOC has brought, five were voluntarily dismissed after less than one year. None went to trial. Only one resulted in a judgment, and a consent judgment at that, with the owners of the Galaxy Cafe agreeing to pay the USOC $3,100 in attorney’s fees. The terms or amount of the USOC’s judgment in that case were not immediately available online.

I’m not a fan of the USOC. It has come across in Washington in recent months as a trademark bully. But this record shows the USOC either is all-bark and no-bite, or it is a lot more selective in the trade name cases it chooses to prosecute in court than it would first seem.

Microsoft Wins Trademark Counterfeiting Case on Summary Judgment

In the Northern District of California case of Microsoft Corp. v. E&M Internet Bookstore, Microsoft brought suit against a company doing business as emeshop.net, and its alleged owner Chien-Wei Chen, for selling counterfeit Microsoft software on eBay.

In the Northern District of California case of Microsoft Corp. v. E&M Internet Bookstore, Microsoft brought suit against a company doing business as emeshop.net, and its alleged owner Chien-Wei Chen, for selling counterfeit Microsoft software on eBay.

Plaintiff and defendants reached a preliminary settlement in which defendants agreed to pay plaintiff $35,000. The parties did not finalize the agreement, however, because Mr. Chen stopped communicating with his attorneys. As a consequence, defendants’ counsel moved to withdraw from the case. The court then ordered defendants to appear in person and show cause as to why they should not be deemed to be in default. Defendants failed to appear.

Microsoft then moved for summary judgment. Defendants’ attorneys submitted a response stating they had not received any communication from Mr. Chen and that, as a result, they would not submit an opposition on defendants’ behalf. Defendants did not appear at the hearing despite being notified when the hearing would take place.

Not surprisingly, the court granted Microsoft’s motion. It summarized the facts as follows:

From April 17 until June 13, 2006, eBay sent defendants approximately 65 auction ‘takedown’ notices concerning Microsoft products that defendants had attempted to sell on eBay. On May 2, an investigator for Microsoft purchased two products from defendants — one unit of Windows XP Professional SP2 and one unit of Office 2003 Professional — that were later analyzed and determined to be counterfeit. Plaintiff also contends it received two complaints from customers regarding counterfeit products sold to them by defendants. In an e-mail to defendant Chen on May 26, a representative from Microsoft warned: ‘we have received samples of counterfeit software distributed through your eBay auctions so it is especially important to verify the legitimacy of your supplier(s).’ In a subsequent e-mail, the Microsoft representative cautioned defendant Chen against continued purchases of software from unauthorized distributors.”

The court found: “The record supports a finding of trademark infringement. Plaintiff has established that it held properly-registered trademarks and that defendants sold two counterfeit products over the internet on May 2, 2006. A reasonable consumer would likely be confused about the authenticity of a counterfeit product bearing the ‘Microsoft’ trademark. Indeed, Microsoft received calls from confused customers who had unknowingly bought counterfeit products from defendants. Defendants have submitted no evidence showing that a genuine issue of fact remains for trial. Plaintiff’s motion for summary judgment with respect to its trademark claim is therefore Granted.”

The court imposed a permanent injunction against the defendants enjoining them from selling counterfeit Microsoft software and from advertising such software on Internet auction sites. For damages, the court awarded Microsoft’s requested sum of $45,000 for trademark and copyright infringement, as well as $5,000 in attorney’s fees and costs.

The case cite is Microsoft Corp. v. E&M Internet Bookstore, Inc., 2008 WL 191346, No. 06-06707 (N.D. Calif., Jan. 22, 2008).