Two Cases Interpret the Trademark Dilution Revision Act

This month’s INTA Bulletin announced: ”First Case Decided Under Trademark Dilution Revision Act Finds No Dilution” (International Trademark Association membership required). To date, two such cases have been decided. Both shed a little light on the post-Moseley v. V. Secret “likelihood of dilution” standard codified at 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c). However, still more light is needed.

In the first case, Louis Vuitton Malletier S.A. v. Haute Diggity Dog, LLC, No. 1-06-321JCC, 2006 WL 3182468 (E.D. Va.), defendants sold novelty pet products under the spoof trademark CHEWY VUITON. The Eastern District of Virginia looked to the Second Circuit for guidance on analyzing plaintiff’s claim of dilution in the context of defendants’ claim of parody. There, “the use of famous marks in parodies causes no loss of distinctiveness, since the success of the use depends upon the continued association with the plaintiff.”

Applying that authority, the court found “the mark continues to be associated with the true owner, Louis Vuitton. Its strength is not likely to be blurred by a parody dog toy product. Instead of blurring Plaintiff’s mark, the success of the parodic use depends upon the continued association with Louis Vuitton.” Therefore, the court dismissed plaintiff’s dilution-by-blurring claim on summary judgment.

As for dilution by tarnishment, the court found that plaintiff provided only a “flimsy theory” that “a pet may some day choke on a Chewy Vuiton squeak toy and incite the wrath of a confused consumer against Louis Vuitton.” The court concluded that no reasonable trier of fact could find for plaintiff based on such evidence, again justifying dismissal on summary judgment.

In the second case, AutoZone, Inc. v. Strick, No. 03-C-8152, 2006 WL 3626770 (N.D. Ill.), the Northern District of Illinois considered whether defendant’s OIL ZONE and WASH ZONE trademarks diluted plaintiffs’ AUTOZONE mark. The court recognized that under the TDRA, “a plaintiff can have a successful dilution claim regardless of whether it can show actual or likely confusion.”

However, the court found plaintiffs had not shown either. It found ”[a]lthough defendants have raised the issue of an inability to prove dilution, plaintiffs have made no attempt to show actual or likely dilution.” Plaintiffs said they planned to present circumstantial evidence of dilution but did not do so in response to the motion. Therefore, the court dismissed their claim on summary judgment.

When the TDRA was enacted, some feared that owners of famous marks would ride roughshod over owners of lesser-known marks. I don’t think that’s going to happen. These cases suggest that, at a minimum, plaintiffs alleging dilution need to establish nationwide fame and then prove with competent evidence that the defendant’s mark is likely to cause the plaintiff’s mark real harm. Speculation is not enough, and promises of future proof are not enough. Nor should they be.

It will be interesting to see what evidence courts accept as proof of likelihood of dilution — particularly at the appellate level.

For background on the TDRA, an article I wrote in October summarizing the Act is available here.

Does MOONRAY Infringe MOONSTRUCK?

Portland-based Moonstruck Chocolate Co. filed a trademark infringement suit January 19 against Duvall, Washington-based Moonray Espresso Corp. and Michael Snow, its alleged owner. Plaintiff’s complaint, filed in the Western District, alleges that defendants’ MOONRAY name, mark, and “moon” design used in connection with their coffee house infringe plaintiff’s MOONSTRUCK name, federally-registered marks, and “moon” design used in connection with plaintiff’s chocolates and “chocolate cafes.” The case was assigned to Judge James Robart.

Ads that Reinforce Geographic Indicators Have their Limitations

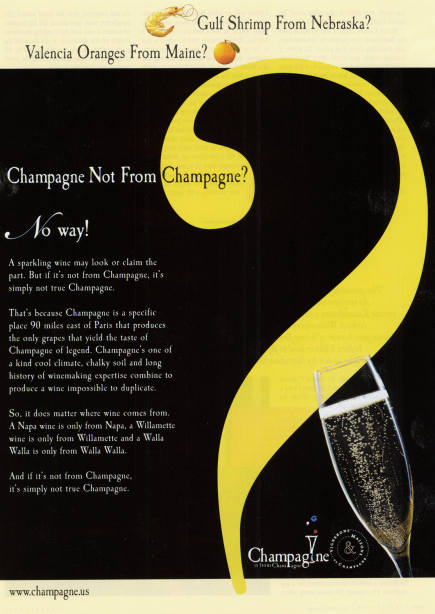

The Vignerons & Maisons of Champagne run an ad each month in Vanity Fair reminding readers that Champagne only comes from Champagne, France. The crux of the message is the bubbly stuff we drink from Napa is merely “sparkling” wine. Ads like this can work for wine because they are backed by precisely-defined appellations. Washington, for example, has nine federally-recognized American Viticultural Areas. That means if a wine does not come from grapes grown in the 6,000 acres due south of Mabton (to the west) and Pasco (to the east), it does not come from Washington’s Horse Heaven Hills.

It’s trickier for other home-grown favorites. Take oysters, for example. For the most part, Washington oysters are all the same species, namely, Crassostrea gigas, or Pacific oysters. But try finding “Pacific oyster” on the menu next time you’re at a seafood restaurant. In all likelihood, you can order Pacific oysters, but you’ll find them identified solely by locale: Puget Sound, Hood Canal, or Grays Harbor. Or, even more likely, by the micro-areas within these regions, like Penn Cove, Skookum, Westcott Bay, Windy Point, Totten Inlet, or Hog Island. In Washington, at least, these areas are not legally defined.

This presents a recurring problem for Seattle-area trademark lawyers. If a grower harvests oysters three miles due east of Penn Cove, in the Saratoga Passage, can it market them as “Penn Cove” oysters? What if its oyster seed came from Penn Cove but was transplanted and harvested in Hood Canal? What if its oysters share the characteristics of oysters grown in Penn Cove but actually come from somewhere far away? Could the hypothetical Penn Cove Oyster Co. successfully argue that PENN COVE refers exclusively to the oysters it sells? (To date, no one has registered PENN COVE as a trademark with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in connection with shellfish, but someday that may change.)

These are largely factual questions that an advertising campaign is not likely to solve. The Champagne ad belies this limitation. It rhetorically asks: “Gulf shrimp from Nebraska?” and “Valencia oranges from Maine?” Clearly, “Gulf” shrimp doesn’t come from Nebraska and “Valencia” oranges don’t come from Maine. But where exactly do those products come from? I suspect that Valencia orange growers and New Orleans shrimpers struggle with these issues as much as our oyster harvesters do. I won’t even ask exactly where Washington’s “Walla Walla Sweet” onions come from.

Four Noteworthy Blogs

The right side of this page lists the “Blogs I Read.” I actually read a lot more than the few listed there. Those are the blogs I consider indispensable. Last night, I added three: the Chicago IP Litigation Blog, Legal Fixation, and TMBrandingCap.com. Each is updated faithfully and well worth your time.

I kind of consider the Chicago IP Litigation Blog a cousin of this blog because it is written by an IP litigator who focuses on decisions from his jurisdiction, namely, the Northern District of Illinois. He has lots of cases to choose from — the Northern District of Illinois has a more active IP case load than I would have guessed — and R. David Donoghue does a great job separating the wheat from the chaff.

Legal Fixation flags new IP developments no matter what the jurisdiction, including a healthy dose of trademark law. It is co-published by Massachusetts attorneys Matthew Saunders and Aaron Silverstein.

TMBrandingCap.com is a new blog that also is solidly in the trademark camp. As best I can tell, it’s published by the semi-anonymous “AAB,” who must be an attorney because he or she spends a good amount of time keeping up with trademark law happenings. Let’s hope he or she continues to do so.

Finally, I can’t help but note that Marty Schwimmer has been on fire lately over at the Trademark Blog. His coverage of the IPHONE trademark flap has been superb. His posts on January 12 and January 17 are especially worthwhile.

Court of Appeals Finds SCOTCHGARD Does Not Infringe STONGARD

In a rare trademark opinion, the Washington State Court of Appeals yesterday found that Defendant/Respondent 3M Co.’s SCOTCHGARD trademark did not infringe Plaintiff/Appellant Stongard, Inc.’s STONGARD or STÔNGÄRD trademarks.

After terminating Stongard in 2003 as a preferred distributor of its SCOTCHCAL automotive paint protection film product, 3M rebranded its product as SCOTCHGARD, a well-known mark 3M had used with other products but had not previously used with film. Stongard interpreted the change as a deliberate attempt to infringe its STONGARD and STÔNGÄRD word and design marks and filed suit.

After a six-day bench trial, King County Superior Court Judge James Cayce determined that plaintiff’s STONGARD and STÔNGÄRD word marks were generic or descriptive without secondary meaning. He found the protection Stongard had obtained through federal registration only extended to its a pink-and-blue logo in a stylized font. Therefore, he limited his likelihood of confusion analysis to the parties’ design marks. Comparing the parties’ logos, Judge Cayce found that confusion was not likely.

The Court of Appeals affirmed that finding. Its unpublished decision, titled 3M Co. v. Stongard, Inc., No. 56911-2-I, 2007 WL 93227 (Wash.App. Div. 1), is available here.