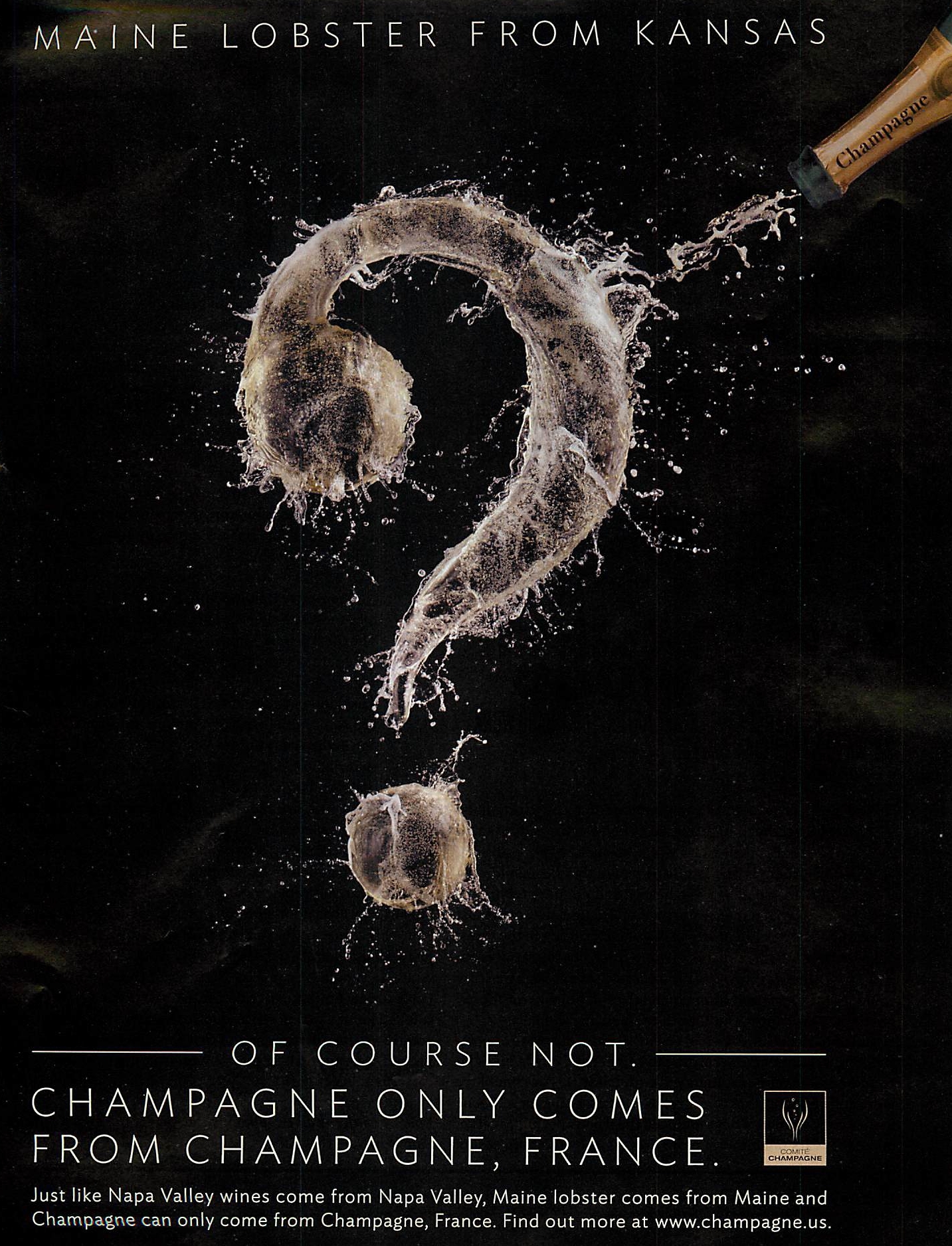

New Advertising Reminds that Champagne Only Comes from Champagne

A friendly reminder: Champagne can only come Champagne, France.

A friendly reminder: Champagne can only come Champagne, France.

Happy New Year!

Just in time for the big event, the Comite Champagne trade association launched a new round of advertising intended to remind Americans that Champagne only comes from the Champagne region of France.

The text says: “Maine lobster from Kansas? Of course not. Champagne only comes from Champagne, France. Just like Napa Valley wines come from Napa Valley, Maine lobster comes from Maine and Champagne can only come from Champagne, France. Find out more at www.champagne.us.”

I have no beef with this message, even though the folks behind the Champagne region have monkeyed with the borders of the region, calling into question (at least in my mind) what the difference really is between Champagne grapes and those grown a stone’s throw outside the region. But clearly, growers within the region have a right to tell consumers that sparkling wine made from grapes grown in the States can’t be Champagne.

NPR had a longish story yesterday about this issue as well, which highlighted what some might say is a confusing practice — wineries stating “methode champenoise,” or “champagne method” on their labels of non-Champagne wines, ostensibly to indicate the use of a traditional means of winemaking. Champagne wineries, of course, cry foul.

But what I’m wondering is what geographic indication trademarks signal to consumers that a good comes from Seattle? I must admit that none immediately come to mind.

First-to-Use Scheme Means U.S. Owners can Appropriate Foreign Trademarks

Presse logos: Paris (left) and Seattle. Nothing wrong with this picture.

This is my first blog post in a while. I’m sorry about that. I’ve been traveling.

In fact, I just got back from Paris. What a town. I’ve said Chicago is the most beautiful city in America. I stand by that proclamation. But I’ve got to give Paris the distinction of being the most beautiful city in the world.

While there, I noticed a familiar trademark — that of Seattle’s Cafe Presse restaurant and bar. Apparently, the logo is also the symbol of newsstands in Paris, which is apropos, since the Seattle establishment has a Parisian and newsstand theme.

I don’t see anything wrong with a Seattle company appropriating a foreign trademark. If the foreign owner hasn’t used the mark in the States, it probably doesn’t have any trademark rights here. So, there should be no problem under trademark law. In such a case, the U.S. company would be the only company with rights in the trademark here.

While Cafe Presse’s use of the French logo appears to be a love letter to Paris, its rights in the mark in the States is all-American. For trademark law purposes, the first party to use a mark in the States generally means it’s the first party to have rights in the States.

(Photos by STL)

Differences in Goods Can Avoid Confusion Even When Trademarks are Identical

Think this is from Delta Airlines’ Web site? Me either.

Think this is from Delta Airlines’ Web site? Me either.

We’ve got DELTA for an airline, and DELTA for faucets.

One of these guys has got to be infringing the other, right?

Nope. Even with exact trademarks, there’s no likelihood of consumer confusion if the products are sufficiently different. If the average consumer wouldn’t think an airline also makes bathroom fixtures, both companies can peacefully coexist even though they share identical trademarks.

Last week, the District of Oregon illustrated this principle when it found that parties with similar marks and similar goods can coexist in their respective markets without one infringing the other.

In Icebreaker Limited v. Gilmar S.P.A., plaintiff Icebreaker moved for summary judgment on its claim for a declaration that its ICEBREAKER trademark did not infringe Gilmar’s ICEBERG trademark, even though both parties use their marks with clothing. The court granted its motion.

“Here the record reflects even though Plaintiff makes some things like dresses and camisoles and workout and exercise apparel that people theoretically could wear anywhere as opposed to only for athletic activities, Plaintiff’s products are demonstrably different from Defendant’s products: Plaintiff designs, markets, and sells its clothing as performance active wear; Plaintiff’s website organizes apparel by activities such as biking, hiking, fishing, mountaineering, running, and skiing; Plaintiff’s stores are organized by activity, and both the website and the stores contain photos and advertisements of people engaged in athletic activities; and Plaintiff advertises its clothing in various sporting and outdoors magazines….

“In contrast,” the court found, “the record reflects Defendant is an Italian fashion company. Defendant’s advertising in various foreign fashion magazines features runway models wearing designer apparel. Defendant’s clothing appears on models in the Milan fashion show.”

In short, active wear just isn’t close enough to high fashion wear, to create a likelihood of confusion — even when both marks begin with the formative “ICE.”

The case cite is Icebreaker Limited v. Gilmar S.P.A., No. 11-309 (D. Or. Nov. 26, 2012) (Brown, J.).

What "Likelihood of Confusion" is and Why it Matters in Trademark Law

A couple weeks ago I had the good fortune to drop in on the IP-core class at the University of Washington School of Law. It’s a good mix of J.D. (regular) and L.LM. (graduate) law students focused on learning the fundamentals of intellectual property law.

The mission? Talk about the importance of the likelihood of confusion in trademark law. I also introduced parody in the context of likelihood of confusion.

Likelihood of confusion is a hugely important concept in trademark law. It’s the basis for a trademark infringement suit. It’s also a bar to getting a trademark registered or a reason to have an existing registration cancelled.

The slides from my presentation are below. It highlights the “likelihood of confusion” factors that courts use to determine whether ordinary consumers would probably think that goods or services come from Source A when they actually come from Source B. If a likelihood of confusion exists, courts can enjoin (prohibit) the junior user from using the trademark that is causing confusion with the senior mark, among other things.

Want a crash course? My slides are accessible below.

Dripping Wax Seals Aren't Just for Bourbon Anymore

A dripping wax seal: Not just for bourbon anymore.

After Maker’s Mark’s solid trade dress victory this summer against Jose Cuervo — in which the Sixth Circuit upheld the district court’s finding the dripping red wax seal was an “extremely strong” trademark that had been infringed — it’s notable to see some dripping wax seals in the beer aisle. (I was there completely by accident, I assure you.)

Now, beer isn’t bourbon, and these seals aren’t red, but it will be interesting to see if Maker’s cries foul. I’m not saying it should, but on the heels of such a nice win, I wouldn’t be surprised if it tried to flex its muscle beyond hard liquor.