Entries in Trademark Infringement (368)

Abercrombie & Fitch Sues in Seattle for Cybersquatting and Unfair Competition

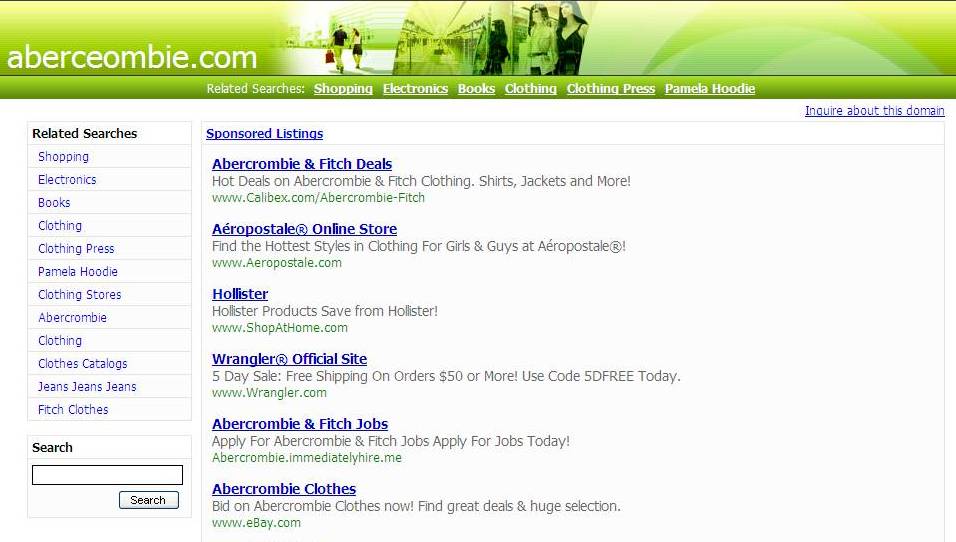

Screen shot from defendants’ Web site at www.aberceombie.com

Screen shot from defendants’ Web site at www.aberceombie.com

Subtlety isn’t their thing.

Abercrombie & Fitch Co. alleges that unknown defendants not only registered a truckload of domain names that are confusingly similar to its ABERCROMBIE and HOLLISTER registered trademarks, but those domain names resolve to Web sites that sell products that compete with Abercrombie & Fitch’s products, including products that allegedly are pirated from Abercrombie.

On December 10, Abercrombie filed suit in the Western District against John Does 1-10. Its complaint alleges cybersquatting, trademark infringement, and unfair competition.

Many of the domain names allegedly at issue include misspellings of ABERCROMBIE and HOLLISTER, such as aberceombie.com, abercromble.com, hollioster.com, and hiollister.com.

Abercrombie alleges the Western District has personal jurisdiction over the defendants because they have conducted business engaged in torts here.

Defendants have not yet appeared or answered the complaint.

The case cite is Abercrombie & Fitch Co. v. John Does 1-13, No. 10-1998 (W.D. Wash.).

Ninth Circuit Affirms Dismissal of Trademark Claim Based on Naked License

FreecycleSunnyvale belongs to The Freecycle Network, an organization that facilitates the recycling of goods.

FreecycleSunnyvale (FS) filed suit against The Freecycle Network (TFN) seeking a judgment of noninfringement arising from a trademark licensing dispute. It then moved for summary judgment on the issue of whether its defense that The Freecycle Network had engaged in a naked license enabled FreecycleSunnyvale to avoid infringing The Freecycle Network’s trademark as a matter of law.

The Northern District of California granted the motion and dismissed The Freecycle Network’s infringement claim.

On appeal, The Freecycle Network argued that it exercised control over its marks through a number of means, namely: (1) its “‘Keep it Free, Legal, and Appropriate for all Ages’ standard and TFN’s incorporation of the Yahoo! Groups’ service terms; (2) the non-commercial services requirement [as expressed in an email between the parties]; (3) the etiquette guidelines listed on TFN’s website; and (4) TFN’s ‘Freecycle Ethos’ which, TFN contends, establishes policies and procedures for member groups, even if local member groups are permitted flexibility in how to apply those policies and procedures.

The Ninth Circuit rejected the sufficiency of those measures and affirmed the district court’s dismissal.

“First, we disagree with TFN’s contentions that the ‘Keep it Free, Legal, and Appropriate for all Ages’ standard and its incorporation of the Yahoo! Groups’ service terms constituted actual controls over its member groups. The undisputed evidence showed that TFN’s licensees were not required to adopt the ‘Keep it Free, Legal, and Appropriate for all Ages’ standard, nor was it uniformly applied or interpreted by the local groups. Similarly, FS was not required to use Yahoo! Groups and was not asked to agree to the Yahoo! Groups’ service terms as a condition of using TFN’s trademarks. Moreover, the Yahoo! Groups’ service terms, which regulate generic online activity like sending spam messages and prohibiting harassment, cannot be considered quality controls over TFN’s member groups’ services and use of the trademarks. The service terms apply to every Yahoo! Group, and do not control the quality of the freecycling services that TFN’s member groups provide. Thus, the ‘Keep it Free, Legal and Appropriate for All Ages’ standard and the Yahoo! Groups’ service terms were not quality controls over FS’s use of the trademarks.

“Second, we conclude that TFN’s non-commercial requirement says nothing about the quality of the services provided by member groups and therefore does not establish a control requiring member groups to maintain consistent quality. Thus, it is not an actual control in the trademark context. Third, because member groups may freely adopt and adapt TFN’s listed rules of etiquette and because of the voluntary and amorphous nature of these rules, they cannot be considered an actual control. For example, FS modified the etiquette that was listed on TFN’s website and TFN never required FS to conform to TFN’s rules of etiquette. Fourth, TFN admits that a central premise of its ‘Freecycle Ethos’ is local enforcement with local variation. By definition, this standard does not maintain consistency across member groups, so it is not an actual control.

“Even assuming that TFN’s asserted quality control standards actually relate to the quality of its member groups’ services, they were not adequate quality controls because they were not enforced and were not effective in maintaining the consistency of the trademarks. Indeed, TFN’s alleged quality controls fall short of the supervision and control deemed inadequate in other cases in which summary judgment on naked licensing has been granted to the licensee.”

Given these findings, the court found that TFN had engaged in naked licensing. Therefore, it found TFN had abandoned its trademark rights.

The obvious lesson here is if a licensor does not control the quality of the goods or services used in connection with the licensed mark, the license is considered to be a naked license. A licensor that engages in naked licensing abandons all rights to the licensed mark. So, licensors, you need not only to have the right to control your licensee’s quality — you need to exercise that right.

The case cite is FreecycleSunnyvale v. The Freecycle Network, __ F.3d. __, 2010 WL 4749044, No. 08-16382 (9th Cir. Nov. 24, 2010).

Western District Denies Injunction Against Canadian Supplement Seller

Plaintiff Preferred Nutrition, Inc., sells health supplements.

It hired defendant Lorna Vanderhaeghe, a Canadian citizen, as an independent consultant to help launch a new line of women’s supplements in Canada. Each supplement in the line ends with the suffix “Sense,” such as ESTROSENSE and MENOSENSE. Ms. Vanderhaeghe’s name and likeness appear on each supplement’s label.

Thereafter, Preferred Nutrition and the Everett, Wash.-based plaintiff Natural Factors Nutritional Products, Inc., began working with Ms. Vanderhaeghe to launch a similar line of products in the United States. From 2003 to 2008, the parties collaborated to sell eight SENSE products in the U.S., which did not feature Ms. Vanderhaeghe’s name or likeness.

In 2008, Natural Factors approached Ms. Vanderhaeghe about using her name and likeness on the American SENSE line. In 2009, it revised its labels to include Ms. Vanderhaeghe’s name and likeness, but later removed references to her. Around the same time, Preferred Nutrition likewise removed Ms. Vanderhaeghe’s name and likeness from its products in Canada.

By January 2010, both Preferred Nutrition and Natural Factors ended their relationship with Ms. Vanderhaeghe, who had made it known she intended to start a competing line of supplements.

In the spring of 2010, Ms. Vanderhaeghe launched a line of women’s supplements in Canada. Each was branded with a name ending in the suffix “Smart,” including ESTROSMART and MENOSMART — the same prefixes used from the SENSE line of products. She also prepared to launch a similar line in the United States.

The only way Americans can purchase Ms. Vanderhaeghe’s SMART products is to travel to Canada or to purchase them from a Canadian online retailer who sells to Americans. Ms. Vanderhaeghe does not sell any products directly from her Web site.

Preferred Nutrition and Natural Factors sued Ms. Vanderhaeghe in the Western District for trademark and trade dress infringement, and moved for a preliminary injunction. The injunction, the court noted, “would prevent Ms. Vanderhaeghe from doing anything to promote her SMART products in the United States or Canada, including the SMART names and the trade dress of the SMART products. It would also require her to refrain from ‘engaging in any acts of unfair competition against [Preferred Nutrition] or [Natural Factors].’ It would force her to stop seeking United States trademark registrations for her products, and to ‘immediately cancel or withdraw’ all pending state and federal trademark registrations.”

Western District Judge Richard Jones denied the motion.

“The court declines to enjoin Ms. Vanderhaeghe’s indirect sales to Americans. The sole claim for which Plaintiffs have established a likelihood of success on the merits is their claim for trade dress infringement. The court does not find a strong likelihood of success even on that claim. Plaintiffs have proven irreparable harm only because they enjoy a presumption of irreparable harm. The balance of hardships, however, strongly favors Ms. Vanderhaeghe. Ms. Vanderhaeghe should not be forced to forego lawful foreign product sales merely to permit Plaintiffs to cut off an unknown volume of sales to Americans.”

The court also noted it “does not have jurisdiction over Ms. Vanderhaeghe’s sales of her products to Canadians. That is a matter for the Canadian court system” and found that Ms. Vanderhaeghe’s plans to enter the U.S. market by selling her products directly to Americans was “too indefinite to support an injunction.”

The case cite is Preferred Nutrition, Inc. v. Vanderhaeghe, No. 10-907 (W.D. Wash. Nov. 22, 2010) (Jones, J.).

Comply with Even Routine Court Orders or Risk Dismissal

In the trademark case of Baxter v. John Doe I-X, Western District Judge Thomas Zilly ordered the parties to show cause why their case should not be dismissed for failing to comply with the court’s deadline for filing a joint status report.

The parties didn’t respond.

So, the court dismissed the case.

I’m not saying the parties didn’t expect or want this result. But it goes to show if you don’t meet the court’s deadlines, you risk drastic sanctions — including having your case dismissed.

The case cite is Baxter v. John Doe I-X, No. 09-1535 (W.D. Wash. Nov. 12, 2010) (Zilly, J.).

Western District Modifies Preliminary Injunction Order Against Under Armour

A battle of batting helmets: Rawlings’ helmet (left), which Rawlings

alleges Under Armour used (right) with Under Armour’s logo

On Oct. 27, Western District Judge Marsha Pechman granted Rawlings Sporting Goods Co.’s motion for a preliminary injunction against Under Armour, Inc., based on Rawlings’ trademark infringement claim. (STL post on the complaint here).

The court found that “in 2008 and 2009, Under Armour placed its own logo on the center-front of Rawlings’s helmet during high school exhibition games and advertising materials used in an Eastbay catalogue, a magazine article, point-of-purchase signage and several websites.”

The court added “there is a likelihood of consumer confusion given that Under Armour has now introduced its own baseball helmet for the marketplace.”

Therefore, the court enjoined Under Armour from placing its logo on Rawlings’ helmet in advertising and promotional materials or on the center-front of its own helmets it offers for sale. The court also ordered Under Armour to “send corrective notices to retailers who have submitted orders for the Under Armour helmet as of entry of this Order.” The court ordered that the corrective notices “inform receiptients of this Court’s preliminary injunction.”

Following the order, Under Armour asked the court to clarify or modify its order with respect to the corrective notices.

On Nov. 10, the court granted the request. It specified that Under Armour’s notice must read:

“Under Armour Inc. has likely infringed on the trademark of Rawlings Sporting Goods Company, Inc. In 2008 and 2009, Under Armour placed its logo on Rawlings’s COOLFLO helmet at several promotional events and advertising materials. This likely confused consumers as to the true producer of the COOLFLO helmet. Therefore, the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington has barred Under Armour from placing its logo on Rawlings’s COOLFLO helmet in future promotional materials and from selling its own Under Armour helmet with its logo on the helmet’s center-front area. The Court has directed Under Armour to issue this notice to all retailers and consumers who have already cemented orders for Under Armour helmets as they may have been confused by Under Armour’s promotional and advertising materials.”

The case cite is Rawlings Sporting Goods Co., Inc. v. Under Armour, Inc., No. 10-933 (W.D. Wash. Nov. 10, 2010) (Pechman, J.).