Entries in Trademark Infringement (368)

Ninth Circuit Affirms Dismissal of Author's Claim of Trademark Infringement

Pro se plaintiff Cherie Phillips wrote a book titled “Wisdom Bible of God.” She claimed she has trademark rights in that title because it is arbitrary and inherently distinctive, and because it has acquired secondary meaning. In her complaint, filed in 2007 in the District of Hawaii, she alleged that defendant Mike Murdock’s book, “The Wisdom Bible,” infringes her trademark rights. (Both parties are depicted above.)

Last year, the District of Hawaii granted summary judgment for Mr. Murdock and Mike Murdock Evangelistic Association, finding that Ms. Phillips’ trademark was descriptive, requiring proof of secondary meaning. “Plaintiff argues that the ‘Wisdom Bible’ title is arbitrary and automatically entitled to trademark protection. Plaintiff’s description of her own writings contained in the book, however, reveals the title ‘Wisdom Bible’ is descriptive. Plaintiff describes her work as a compendium and reinterpretation of ancient wisdom from the great religions and philosophies. The book is a collection of the wisdom of ancient religious texts and philosophers; a book meant to be an authoritative text, a ‘bible,’ of ancient wisdom. Phillips’ work is the collection of sacred texts of the Stoic religion. The text of the book falls under the accepted definition of the word ‘bible,’ as defined as a book regarded as the authoritative text on a subject. The title ‘Wisdom Bible’ describes the contents, and what the author intends the book to convey, precisely.”

The court also rejected Ms. Phillips’ claim of secondary meaning. “Here, Plaintiff asserts that her work is broadly known. Plaintiff states that the title Wisdom Bible has been used in commerce since 1999, when the book was allegedly sold to ‘Canadians’, alleges that a copy of the work was sent to the Virginia State Library, and alleges that in 2001 the book was ‘placed on the worldwide internet.’ Phillips fails to proffer any evidence in support of the statements.”

Ms. Phillips appealed dismssal on these grounds, but to no avail. On July 28, the Ninth Circuit affirmed the court’s determination in summary fashion, saying little other than: “The district court properly granted summary judgment on Phillips’s trademark infringement claim because the term ‘Wisdom Bible’ is descriptive, and Phillips failed to raise a triable issue that the term has acquired secondary meaning.”

The case cite is Phillips v. Mike Murdock Evangelistic Association, No. 08-16925, 2009 WL 2242423 (9th Cir.) (July 28, 2009).

Western District Trademark Case Among Eight Nationwide Against Google

Eric Goldman reported a while back that a Western District case is one of eight currently pending against Google, Inc., for trademark infringement. In Soaring Helmet Corp. v. Bill Me, Inc., Soaring Helmet alleges that competing motorcycle helmet seller Bill Me, Inc., d/b/a Leatherup.com, purchased plaintiff’s VEGA trademark as a keyword from Google. When a person searches Google for “VEGA helmets,” the complaint states, Google returns a sponsored link stating that Bill Me offers “50% off Vega Helmets,” even though Bill Me does not sell plaintiff’s VEGA helmets.

Plaintiff claims this amounts to contributory trademark infringement. “Defendant Google, through its keyword advertising program, contributes to the aforementioned trademark infringement by knowingly encouraging advertisers to use Soaring Helmet’s Mark in false and misleading advertisements that have caused, and is likely to cause confusion, mistake, or deception of consumers, to the detriment of Soaring Helmet.”

Says Prof. Goldman: “…Google treated Soaring Helmet’s initial cease-and-desist letter as a trademark opt-out and blocked subsequent references to Vega in Leatherup.com’s ad copy. Thus, unless Soaring Helmet seeks to reach back to the ads displayed before its C&D, it appears Soaring Helmet is trying to hold both Google and Leatherup.com [liable] simply for showing ads triggered by Soaring Helmet’s “Vega” trademark.”

Neither defendant has answered the complaint, which plaintiff amended yesterday to identify Bill Me with more particularity.

The case cite is Soaring Helmet Corp. v. Bill Me, Inc., No. 09-789 (W.D. Wash.).

Bainbridge Island Design Firm Claims Amazon.com Infringes Its Trademark

Seattle’s technology news blog TechFlash ran a story on Friday about a Bainbridge Island, Wash.-based design firm that claims Amazon.com is infringing its trademark.

The dispute involves Web designer Geoffrey Daigle’s registration for WINDOW SHOPPING for “information services, namely, providing information on a wide variety of topics, namely news, weather, arts, counseling services, automobiles, childcare, consumer products, sports, travel, and entertainment, namely, movies, videos, and music via a global computer network.” Mr. Daigle’s firm, Daigle Design, uses the mark in connection with a Web portal to Amazon.com and other retailers.

At issue is Amazon.com’s recent adoption of AMAZON WINDOWSHOP in connection with a beta online shopping feature that enables users to zoom in on items and view them in 3-D.

Daigle Design sent Amazon.com a cease-and-desist letter in February, the post says. Amazon.com reportedly responded by claiming that WINDOW SHOPPING is generic.

In January, Amazon.com filed its own application to register AMAZONWINDOW SHOP and Design.

The post quotes me as saying it’s unusual for a small company to go after a behemoth like Amazon.com.

No word on whether Mr. Daigle intends to file suit.

Additional coverage yesterday in the Kitsap Sun.

Western District Holds Maker of Worm Composting Products in Contempt

As STL reported in November, the Western District found that defendants Providnet Co. Trust and Barry Russell likely infringed plaintiff Cascade Manufacturing Sales, Inc.’s trademark rights in WORM FACTORY in connection with the sale of worm composting bins, and imposed a preliminary injunction against them.

On Jan. 7, the court clarified that its injunction extended to the phrase “Factory of Worms” as well as “Worm Factory,” but not “Worm Wrangler,” which both parties use to describe their products. The court also cautioned defendants to comply with its earlier order.

Apparently, defendants failed to do so. On July 2, Judge Ronald Leighton found them to be in contempt. The court imposed a $5,000 fine, which it said it would exonerate if defendants demonstrate they have met the following terms by July 13. In summary, defendants must:

- Send a letter to each of their distributors mandating that they stop using the phrase “Worm Factory,” “Factory of Worms” or other such terms in connection with defendants’ products;

- Remove all references to “factory” in tags, product descriptors, meta tags, or any other materials on defendants’ Amazon and eBay stores;

- Remove all references to “factory” on their Web sites; and

- Remove “factory” from their accounts on each keyword advertising medium that they use.

I’m happy to report that western Washington appears to be Worm Central, with all parties in the case hailing from this neck of the woods.

The case cite is Cascade Manufacturing Sales, Inc. v. Providnet Co. Trust, No. 08-5433 (W.D. Wash. July 2, 2009).

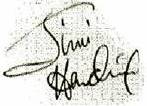

Western District Finds Use of Hendrix Name Fair But Use of Signature Infringing

Screen shot from defendants’ former Web site depicting Hendrix mark

Screen shot from defendants’ former Web site depicting Hendrix mark

Defendants’ use of HENDRIX and JIMI HENDRIX was fair use of plaintiffs’ trademarks to describe the images depicted on their products, the Western District preliminarily found on July 2. However, the court also found defendants’ domain names containing those marks, a guitar and “headshot/bust” logo, and Jimi Hendrix’s signature infringe plaintiffs’ trademarks and enjoined further use pending trial.

Defendant Andrew Pitsicalis was formerly associated with Craig Dieffenbach and Electric Hendrix, LLC — defendants the court enjoined from using various JIMI HENDRIX trademarks in connection with the sale of vodka (STL discussion of that case here). In 2008, Mr. Pitsicalis formed HendrixLicensing.com LTD, which markets posters, art prints, apparel, and novelty items bearing the name, signature, likeness, and/or art created by Jimi Hendrix.

Plaintiffs Experience Hendrix, LLC, and Authentic Hendrix, LLC, sought a preliminary injunction against the defendants’ use of their trademarks by maintaining the hendrixlicensing.com and hendrixartwork.com domain names; using a guitar and “headshot/bust” logo; incorporating the HENDRIX and JIMI HENDRIX trademarks in various products; and placing Mr. Hendrix’s signature on various products. (Past STL discussion of the case here.)

After receiving the motion, defendants stopped using the domain names, as well as the guitar and “headshot/bust” logo, and did not dispute the infringing nature of those things. Defendants solely argued they are making fair use of Jimi Hendrix’s name and signature.

The court agreed in part and disagreed in part. With respect to use of the HENDRIX and JIMI HENDRIX names, the court leaned heavily on the the case of Cairns v. Franklin Mint Co., 292 F.3d 1139 (9th Cir. 2002), in finding the use was fair. “To the extent the names ‘HENDRIX’ or ‘JIMI HENDRIX’ serve merely to describe the associated image, i.e., to identify plaintiffs’ ‘product’ Jimi Hendrix, who is depicted within, or whose artwork is shown in, defendants’ posters or other products, the use is analogous to that in Cairns. As in Cairns, plaintiffs have no post-mortem rights of publicity, and they cannot preclude anyone from creating and then selling sketches, portraits, caricatures, dolls, bobbleheads, or other likenesses of Jimi Hendrix. In addition, plaintiffs offer no evidence that they have trademarks or service marks incorporating fonts similar to the stylized lettering used by defendants, except for Jimi Hendrix’s signature, which will be discussed in the next section. Other than the signature, plaintiffs’ registrations for ‘HENDRIX’ and ‘JIMI HENDRIX’ are in plain typeface. Thus, defendants’ use of distinctive lettering does not itself inappropriately imply a relationship with plaintiffs.”

With regard to Mr. Hendrix’s signature, the court found defendants’ use was not fair. “Defendants have represented to the Court that the signature is authentic, was purchased on ‘eBay’ by Craig Dieffenbach, and was conveyed in electronic form to Mr. Pitsicalis. Defendants use the signature on products, for example, dart game accouterments such as targets, score boards, and dart flights, containing no likeness of Jimi Hendrix. During oral argument, counsel for defendants indicated that defendants are now confining their use of the signature to posters, fine art prints, and apparel. The Court interprets counsel’s remark as a concession that defendants’ use of Jimi Hendrix’s signature constitutes branding, and it is not exempted from infringement liability by either the nominative or the classic fair use doctrine.”

With regard to Mr. Hendrix’s signature, the court found defendants’ use was not fair. “Defendants have represented to the Court that the signature is authentic, was purchased on ‘eBay’ by Craig Dieffenbach, and was conveyed in electronic form to Mr. Pitsicalis. Defendants use the signature on products, for example, dart game accouterments such as targets, score boards, and dart flights, containing no likeness of Jimi Hendrix. During oral argument, counsel for defendants indicated that defendants are now confining their use of the signature to posters, fine art prints, and apparel. The Court interprets counsel’s remark as a concession that defendants’ use of Jimi Hendrix’s signature constitutes branding, and it is not exempted from infringement liability by either the nominative or the classic fair use doctrine.”

Since neither doctrine applied, the court found defendants’ use of Mr. Hendrix’s signature was likely to cause confusion — an issue defendants did not address. Therefore, the court concluded the requested injunction was appropriate.

The case cite is Experience Hendrix, LLC v. HendrixLicensing.com, LTD, No. 09-285 (W.D. Wash. July 2, 2009) (Zilly, J.).