Entries by Michael Atkins (1064)

Federal Registration Owned by Someone Else No Defense to Cybersquatting

This Central District of California case of Monex Deposit Co. v. Gilliam efficiently dispatched a creative but unpersuasive defense to cybersquatting: “You don’t have any trademark rights to enforce against me, since someone else owns the federal registration to that mark. They’re the exclusive, nationwide user of the mark — not you.”

The court’s analysis:

“Jason Gilliam’s second argument is that Monex cannot possibly own the mark ‘Monex’ because other companies have registered trademarks of the word ‘Monex.’ However, a mark can have more than one owner and the Lanham Act permits concurrent registrations of the same mark, provided there is not likely to be confusion, mistake, or deception. Jason Gilliam implicitly acknowledges this fact by pointing out the various other companies in other industries that use the word ‘Monex’ as a mark. Jason Gilliam has presented no evidence that another entity has the right to use the ‘Monex’ mark to designate services related to trading in precious metals or lending funds for the purchase of precious metals. Additionally, Monex has submitted a declaration indicating that no other entity is using the ‘Monex’ mark to designate those types of services.”

This led the court to deny Mr. Gilliam’s motion for summary judgment.

The case cite is Monex Deposit Co. v. Gilliam, __ F.Supp.2d __, 2009 WL 4456564, No. 09-287 (C.D. Calif. Dec. 3, 2009).

Western District Finds Trademark Claims Had Enough Merit to Avoid Fees Award

In Atlas Equipment Co., LLC v. Weir Slurry Group, Inc., plaintiff and a third-party defendant sought attorney’s fees under the Lanham Act against counterclaimants/third-party plaintiffs Weir Slurry and Weir Minerals Australia, Ltd. (collectively, “Weir”), arguing those parties’ counterclaims and third-party claims for “reverse passing off” and trade dress infringement were baseless and pursued for too long. Though the Western District dismissed the subject claims on summary judgment, it did not agree they were so lacking that the prevailing parties deserved a fees award.

Judge Thomas Zilly explained:

“Before alleging its claim for ‘reverse passing off,’ Weir analyzed a pump sold by Atlas Equipment Co., LLC, and discovered that the pump casing, which originally bore Weir’s trademark, had been altered; metallographic testing revealed that the raised letters AH WARMAN had been ground off the casing. Although Weir was not able through discovery to establish that the adulterated casing was produced by Weir, a fact Weir was required to prove as an element of its ‘reverse passing off’ claim, the Court is satisfied that Weir’s assertion of the claim met the criteria of Rule 11(b). Moreover, Weir’s inability to trace the pump casing to one of its foundries does not undermine the legitimacy or reasonableness of Weir’s discovery efforts; Weir could not have known in the absence of discovery how the casing arrived at its doctored state. Finally, the Court is persuaded that Weir seasonably abandoned its ‘reverse passing off’ claim.

“With regard to Weir’s trade dress infringement claim, the Court concludes that Weir relied on a ‘good faith argument for an extension … of existing law.’ Weir raised genuine issues of material fact as to two of the three elements of its trade dress infringement claim, and as to the other element, namely functionality, the law is not fully developed and Weir presented non-frivolous, and rather challenging, contentions to support its position. Finally, the Court also takes into account that the party initiating this declaratory judgment action was Atlas Equipment Co., LLC, and not Weir.”

The case cite is Atlas Equipment Co., LLC v. Weir Slurry Group, Inc., 2009 WL 4430701, C07-1358Z (W.D. Wash. Nov. 30, 2009) (Zilly, J.).

Second Circuit Once Again Remands "Mr. Charbucks" Dilution Decision

The MR. CHARBUCKS dilution saga continues. (See previous STL posts on the case here and here.)

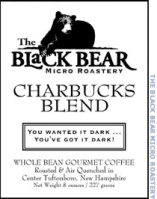

In 2005, the Southern District of New York found that defendant Wolfe’s Borough Coffee, Inc.’s MR. CHARBUCKS trademark for coffee did not dilute Starbucks Corp.’s STARBUCKS trademark under the former Federal Trademark Dilution Act (FTDA).

In 2005, the Southern District of New York found that defendant Wolfe’s Borough Coffee, Inc.’s MR. CHARBUCKS trademark for coffee did not dilute Starbucks Corp.’s STARBUCKS trademark under the former Federal Trademark Dilution Act (FTDA).

Starbucks appealed. While the appeal was pending, Congress enacted the Trademark Dilution Revision Act (TDRA), which provided a new framework for judging the existence of dilution, including substituting a “likelihood of dilution” standard for the “actual dilution” standard the district court had applied under the FTDA. In response, the Second Circuit vacated the district court’s findings and remanded for further proceedings.

On remand in 2008, the Southern District of New York applied the new standard and found no likelihood of dilution by blurring or dilution by tarnishment — the two forms of dilution expressed in the TDRA. Starbucks again appealed.

On Dec. 3, the Second Circuit affirmed the district court’s finding that Starbucks had failed to establish a likelihood of dilution by tarnishment, in large part because Wolfe’s used MR. CHARBUCKS to promote high quality dark-roasted coffee.

However, the Second Circuit found the district court erred in applying the statutory factors when it determined that Starbucks had failed to establish the existence of a likelihood of dilution by blurring. The court remanded the issue once again to the Southern District of New York for further proceedings consistent with the appellate court’s analysis.

Here’s the analysis in a nutshell:

The Second Circuit found the district court did not clearly err in finding the CHARBUCKS marks were minimally similar to Starbucks’ marks. “Upon its finding that the marks were not substantially similar, however, the District Court concluded that ‘[t]his dissimilarity alone is sufficient to defeat [Starbucks’] blurring claim, and in any event, this factor at a minimum weighs strongly against [Starbucks] in the dilution analysis.’ We conclude that the District Court erred to the extent it required ‘substantial’ similarity between the marks, and, in this connection, we note that the court may also have placed undue significance on the similarity factor in determining the likelihood of dilution in its alternative analysis.”

The Second Circuit found the court’s requirement that the marks be “substantially similar” no longer applies in light of the TDRA. “Indeed, one of the six statutory factors informing the inquiry as to whether the allegedly diluting mark ‘impairs the distinctiveness of the famous mark’ is ‘[t]he degree of similarity between the mark or trade name and the famous mark.’ Consideration of a ‘degree’ of similarity as a factor in determining the likelihood of dilution does not lend itself to a requirement that the similarity between the subject marks must be ‘substantial’ for a dilution claim to succeed. Moreover, were we to adhere to a substantial similarity requirement for all dilution by blurring claims, the significance of the remaining five factors would be materially diminished because they would have no relevance unless the degree of similarity between the marks are initially determined to be ‘substantial.’ Such requirement of substantial similarity is at odds with the federal dilution statute, which lists ‘degree of similarity’ as one of several factors in determining blurring. Accordingly, the District Court erred to the extent it focused on the absence of ‘substantial similarity’ between the Charbucks Marks and the Starbucks Marks to dispose of Starbucks’ dilution claim. We note that the court’s error likely affected its view of the importance of the other factors in analyzing the blurring claim, which must ultimately focus on whether an association, arising from the similarity between the subject marks, “impairs the distinctiveness of the famous mark.’

“Turning to the remaining two disputed factors—(1) whether the user of the mark intended to create an association with the famous mark, and (2) whether there is evidence of any actual association between the mark and the famous mark—we conclude that the District Court also erred in considering these factors.

“The District Court determined that Black Bear [Wolfe’s] possessed the requisite intent to associate Charbucks with Starbucks but that this factor did not weigh in favor of Starbucks because Black Bear did not act in ‘bad faith.’ The determination of an ‘intent to associate,’ however, does not require the additional consideration of whether bad faith corresponded with that intent. The plain language of section 1125(c) requires only the consideration of ‘[w]hether the user of the mark or trade name intended to create an association with the famous mark.’ Thus, where, as here, the allegedly diluting mark was created with an intent to associate with the famous mark, this factor favors a finding of a likelihood of dilution.

“The District Court also determined that there was not an ‘actual association’ favoring Starbucks in the dilution analysis. Starbucks, however, submitted the results of a telephone survey where 3.1% of 600 consumers responded that Starbucks was the possible source of Charbucks. The survey also showed that 30.5% of consumers responded ‘Starbucks’ to the question: ‘[w]hat is the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the name ‘Charbucks.” In rejecting Starbucks’ claim of actual association, the District Court referred to evidence supporting the absence of ‘actual confusion’ to conclude that ‘the evidence is insufficient to make the … factor weigh in [Starbucks’] favor to any significant degree.’ This was error, as the absence of actual or even of a likelihood of confusion does not undermine evidence of trademark dilution.”

The Second Circuit separately found MR. CHARBUCKS was not excepted from the TDRA as a parody; the district court did not err in finding no likelihood of dilution under New York state law; and the district court did not err in finding that MR. CHARBUCKS does not create a likelihood of confusion.

The case cite is Starbucks Corp. v. Wolfe’s Borough Coffee, Inc., __ F.3d. __, 2009 WL 4349537, No. 08-3331 (2nd Cir. Dec. 3, 2009).

Cool But Scary: Trademark Filings Can Signal Product Strategy

Seattle TechFlash blogger Eric Engleman wonders here and here whether Amazon.com’s federal trademark application signals that the company’s KINDLE electronic book reader will soon turn into a social networking device.

As he reports, Amazon.com has applied on an intent-to-use basis to register KINDLE (Serial No. 77769510) for “Online social networking services; providing a website for the purposes of social networking; providing online computer databases and online searchable databases in the field of social networking; providing information in the field of social networking.”

For the observer, it’s kind of cool that one can learn this type of information simply by searching the Patent and Trademark Office’s database.

For the owner of a trademark application, it’s kind of scary.

Trademark Tips for Green Startups Apply to All Companies

Graham & Dunn’s own GreenTech blog is on a roll with three posts in recent weeks on trademark issues affecting the “green economy”:

- The post, “Trademarks and ‘Green Depletion,’” questions whether green startups are running out of good names. (Fortunately, they’re not.)

- Part 1 of “Trademark Basics for Startups — Selecting a Company Name” provides a primer that new companies — green or otherwise — should consult before consulting their lawyer. Always a good tip: register your domain name as soon as you pick your company’s name. It’ll be snapped up sooner than you think.

- Part 2 of the post focuses on selecting, clearing, adopting, and protecting a new trademark.

Interesting info, which isn’t limited to green companies.