Entries in Genericism (21)

The Parrot Lady vs. The Parrot Lady over "The Parrot Lady" Trademarks

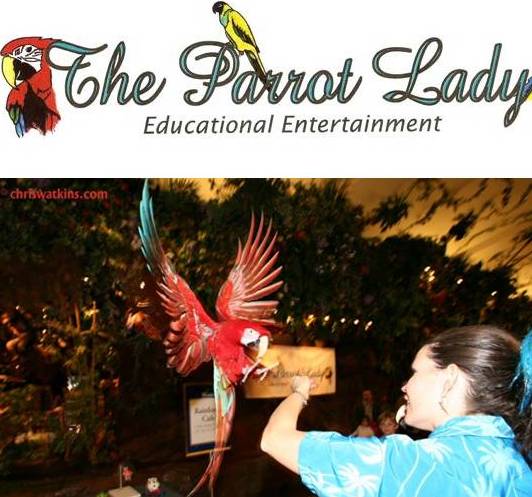

Screen shot from plaintiff’s “The Parrot Lady” Web site

Screen shot from plaintiff’s “The Parrot Lady” Web site

On April 22, Debbie Goodrich filed suit against Karen Allen in the Western District of Washington.

Plaintiff provides entertainment and other services under the name “The Parrot Lady.” Her complaint states she obtained a Washington business license under the name “The Parrot Lady Educational Entertainment” in 2001 and registered the parrotlady.com domain name in 2005.

Defendant owns a federal registration for THE PARROT LADY for “Exotic bird breeding and grooming.” The registration claims a first-use date in 1995. The complaint states that defendant owns a Torrance, Calif. sole proprietorship under the name “Birds & More” and maintains a website accessible at www.birdsandmore.com. The complaint alleges that defendant uses her mark in connection with bird-related goods and services.

Plaintiff alleges defendant or her representative has contacted a number of third parties complaining about plaintiff’s use of “The Parrot Lady” in advertising. The complaint states such third parties include Facebook, Critter Fest, and a Seattle-area YMCA, and those parties have removed advertisements publicizing plaintiff.

Plaintiff seeks an order declaring that her use of THE PARROT LADY does not infringe defendant’s rights in THE PARROT LADY and claims superior rights in the mark in Washington. She also seeks to cancel defendant’s registration, alleging it is generic “for a woman having expertise in breeding and grooming exotic birds, such as parrots.”

The case cite is Goodrich v. Allen, No. 11-687 (W.D. Wash.).

PIE-brand Pie is the New CUPCAKE-brand Cupcake

Seattle pie maker Pie’s logo

Seattle pie maker Pie’s logo

And Seattle’s newest pie maker is Pie.

It stands to reason, then, that PIE-brand pie is the new CUPCAKE-brand cupcake.

Photo by STL

"First-Class Mail" is a Protectable (and Registered) Trademark?

I ordered some photos online, which were delivered to me last week. The envelope was marked “USPS FIRST-CLASS MAIL.” That was expected, because I asked that the photos be sent by first-class mail. What wasn’t expected was the statement at the bottom of the mailing label that “FIRST-CLASS MAIL IS A REGISTERED TRADEMARK OF THE UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE.”

Well, that’s true; I looked it up. In 1978, the U.S. Postal Service obtained a federal registration for FIRST-CLASS MAIL in connection with “delivery services — namely, delivery of letters and goods by mail,” with the word “mail” disclaimed as generic. (Interestingly, the claimed first-use date is July 1, 1863.)

But FIRST-CLASS MAIL is a protectable trademark?

It seems awfully generic to me. Not that I had much choice in the class of mail service I ordered, but if I had, I would have requested that the photos be delivered “first-class” because they presumably would be delivered faster than second class, third class, book rate, or whatever other classes of service that exist. I also would think that “first-class” delivery would be cheaper (though slower) than overnight delivery. In other words, by specifying delivery by “first-class mail,” I used the words that denoted the specified class of service I desired. A first-class job is a job that someone performs at the highest level. A first-class seat is a seat that comes with the best service. How could I communicate the service I wanted without using the words “first-class”? That would seem to make the mark generic.

Now, the U.S. Postal Service would say that FIRST-CLASS MAIL only means one thing — a particular service that you can get from the U.S. Postal Service. In other words, the mark isn’t generic because it identifies the source of the service. But for me, the portion of the mark that conveys that information is the portion the U.S. Postal Service disclaimed: “mail.” To my mind, Federal Express and United Parcel Service deliver letters and packages, but they don’t deliver “mail.” In any case, I don’t see why private delivery companies shouldn’t be able to denote a certain level of service as being “first class.” I suppose if it’s a descriptive mark, and the U.S. Postal Service has had its registration since the ’70s, it would be well-nigh incontestable, cutting off an attack on grounds of descriptiveness. But I still think “first-class mail” denotes the service rather than the provider of the service. And if not, it’s the disclaimed portion of the mark that conveys that distinction — the word the U.S. Postal Service says isn’t capable of doing so.

In the end, it seems silly to me that an online photo printer feels the need to clarify that by arranging to have the photos I ordered delivered in the manner I specified, it’s not infringing the U.S. Postal Service’s trademark.

Isn’t that obvious?

Western District Holds Cancellation is Not a Valid Independent Claim

In Basel Action Network v. International Association of Electronics Recyclers, both parties are non-profit organizations that certify businesses that recycle electronics products.

In June 2010, Basel sued IAER for a declaratory judgment that its use of the terms “certified electronics recycler” and “electronics recycler” does not infringe IAER’s CERTIFIED ELECTRONICS RECYCLER certification mark. Basel also sought to cancel the CERTIFIED ELECTRONICS RECYCLER registration on the ground that it is generic, among other grounds. (STL post on the complaint here.)

IAER moved to dismiss Basel’s claims.

On Dec. 13, Western District Judge Richard Jones found that Basel had not presented a justiciable controversy sufficient to sustain its declaratory judgment action.

The court then considered what appears to be a novel question in the Ninth Circuit: Can a plaintiff sustain an independent cause of action to cancel a defendant’s registration under Section 37 of the Lanham Act?

The court answered the question in the negative.

“The court holds that a party seeking cancellation of a registered mark must not only state an Article III controversy that cancellation can remedy, it must also state a valid independent cause of action that encompasses the controversy,” the court held. “The court reaches this conclusion for several reasons. First, Section 37 does not speak of a ‘controversy involving a registered mark,’ but rather an ‘action involving a registered mark.’ Second, if Congress had intended Section 37 to support a cause of action by itself, the court would expect the statute to explicitly provide for a cause of action. Third, no court has ever held that an Article III controversy that cannot stand as an independent claim can support a cancellation request.”

The court went on to find: “Every court to consider the issue has required a valid independent cause of action as a precondition for invoking Section 37’s cancellation remedy. The court in Universal Sewing Mach. Co. v. Std. Sewing Equip. Corp., 185 F. Supp. 257 (S.D.N.Y. 1960), reached the same conclusion as this court. The plaintiff there raised claims involving the registered mark, but none of them were cognizable in federal court. The court held that ‘absent some other basis of jurisdiction, a suit for cancellation by one in plaintiff’s position may not be independently maintained in this court.’ In Thomas & Betts Corp. v. Panduit Corp., 48 F. Supp. 2d 1088, 1093 (N.D. Ill. 1999), the court held that Section 37 does not by itself support a cause of action. It explained that the viability of the plaintiff’s cancellation claim depended on the viability of its separate Lanham Act unfair competition claim. If this court were to find a party could invoke Section 37 merely by articulating an Article III controversy, it would apparently be the first court to do so.”

The case cite is Basel Action Network v. International Association of Electronics Recyclers, No. 10-931 (W.D. Wash. Dec. 13, 2010) (Jones, J.).

Ninth Circuit Concludes Court Erred in Finding "Advertising.com" is Descriptive

One of AOL Advertising’s (top) and Advertise.com’s design marks

AOL Advertising, Inc., sued Advertise.com, Inc., for trademark infringement. At issue were AOL’s registered design marks for ADVERTISING.COM. Advertise.com defended on the ground that the marks are generic and, therefore, are not protectable as trademarks.

AOL filed in the Eastern District of Virginia, which transferred the case to the Central District of California.

The Central District of California granted AOL’s motion for a preliminary injunction. It enjoined Advertise.com from using “any design mark or logo that is confusingly similar to the stylized forms of AOL’S ADVERTISING.COM marks” or using “the designation and trade name ADVERTISE.COM or any other designation that is confusingly similar to AOL’s ADVERTISING.COM marks.” In doing so, it found that ADVERTISE.COM is descriptive rather than generic.

Advertise.com appealed the portion of the order that enjoined Advertise.com from using “the designation and trade name ADVERTISE.COM or any other designation that is confusingly similar to AOL’s ADVERTISING.COM marks.” For some reason, it did not appeal the remainder of the order.

On Aug. 3, the Ninth Circuit reversed and vacated the subject portion of the injunction.

“This does not appear to be the ‘rare case’ in which the addition of a [top-level domain] to a generic term results in a distinctive mark,” the court found. “Rather, the record before us demonstrates that Advertise.com is likely to rebut the presumption of validity and prevail on its claim that ADVERTISING.COM is generic. How, then, did the district court reach the opposite conclusion? Examining its decision, we conclude that it did so due to an error of law and therefore abused its discretion in granting the injunctive relief challenged here.

“The district court’s analysis of whether ADVERTISING.COM is generic is brief and never explicitly states the standard the court applied. The explanation of its conclusion that ADVERTISING.COM is descriptive, however, convinces us that it did not apply the correct legal standard to the facts before it. The court’s reasoning appears in a single sentence that reads ‘The term ‘advertising’ describes the services that AOL offers, and the ‘.com’ either indicates a commercial entity, use of the internet in association with the mark, or describes the internet-related nature of AOL’s services.

“We conclude that the district curt did not correctly apply the legal standard for determining whether a mark is generic. Even if we credit the district court’s rationales as factually accurate — i.e., if we assume that the addition of ‘.com’ serves the three identified functions — ADVERTISING.COM still conveys only the generic nature of the services offered. That ‘.com,’ when added to a generic term, ‘indicates a commercial entity’ does not suffice to establish that the composite is distinctive, much as AOL would not have created a protectable mark by adopting the designation ‘Advertising Company.’”

The case cite is Advertise.com, Inc. v. AOL Advertising, Inc., __ F.3d __, 2010 WL 3001980, Nos. 10-55069 and 10-55071 (9th Cir. Aug. 3, 2010).