Entries by Michael Atkins (1064)

Glassybaby Appeals Trade Dress Dismissal, Then Apparently Settles

Appeal dismissed by stipulation:

Appeal dismissed by stipulation:

Glassybaby’s candle holder (left) and one made by Northern Lights.

The Western District found Glassybaby’s design generic.

Glassybaby LLC, the Seattle maker of upscale candle holders, sued Northern Lights Enterprises Inc. and another defendant for making and selling candle holders that Glassybaby alleged infringed its trade dress (STL post here).

On Sept. 30, the Western District found Glassybaby’s trade dress is generic and dismissed its claims.

Glassybaby appealed the decision to the Ninth Circuit.

Today, the Ninth Circuit ordered a Dec. 15 conference with the parties cancelled. It stated that, “Pursuant to stipulation of the parties, this appeal is voluntarily dismissed.”

Looks like the parties have settled.

Wonder whether we’ll see the defendants (or others) selling Glassybaby look-alikes.

The case cite is Glassybaby LLC v. Northern Lights Enterprises Inc., No. 11-35899 (9th Cir. Nov. 15, 2011).

Article Explains Transformative Use Doctrine in Publicity Rights Cases

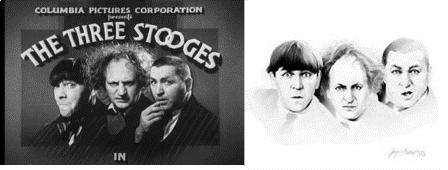

Not transformative: The Three Stooges (left) and artist’s literal depiction

Not transformative: The Three Stooges (left) and artist’s literal depiction

To help prepare for my right of publicity talk earlier this month with fellow Seattle attorney Mel Simburg, I came across this good summary of the “transformative use” doctrine, which courts have recognized as carving out a First Amendment exception to publicity rights claims.

Transformative use occurs when an artist embellishes the depiction of a personality rights holder, such that consumers purchase the good containing the depiction because of the artist’s rendering, rather than because the good depicts a celebrity or other personality rights holder.

A classic example of non-transformative use was artist Gary Saderup’s sketched rendering of The Three Stooges. It was a literal — almost photographic — depiction of the Stooges, which the California Supreme Court found consumers purchased because they liked The Three Stooges, rather than because of Mr. Saderup’s artistic rendering (skillful though it was). Because consumers purchased goods for the celebrity rather than an artistic comment on the celebrity, the court found the use was not transformative and, therefore, it was not excepted from California’s right of publicity statute. See Comedy III v. Saderup, 21 P.3d 797 (Calif. 2001).

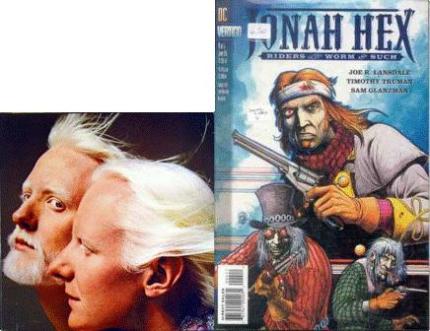

Transformative: Johnny and Edgar Winters (left) and embellished depiction

By contrast, sixties rockers Johnny and Edgar Winters’ right of publicity claim fell short against DC Comics in the same court two years later. The Winter brothers objected to their unauthorized depiction as “Johnny and Edgar Autumn” in DC Comics’ Jonah Hex comic book. Applying the transformative use test, the California Supreme Court found that the Winter brothers were merely the “raw materials” for the artist’s use in the comic book. Therefore, the court found the use was transformative and thus did not violate the brothers’ statutory right of publicity. See Winter v. DC Comics, 69 P.3d 473 (Calif. 2003).

As the article explains, which side of the divide a particular use falls on dictates whether it is likely excepted from a competing right of publicity; in other words, it dictates which interest wins: the celebrity’s right of publicity or the artist’s freedom of expression.

The article also identifies the states that recognize a statutory right of publicity, and states in which the right is descendible to heirs after death.

It’s good reading.

Drafting an Enforceable Injunction Requires Specificity, Plain English

I’ll be speaking at the “Fed Court Boot Camp Conference: How to Practice in Federal Court” CLE on Dec. 2.

One of my topics is preliminary injunctive relief. One thing I’m sure to address is the content of the injunction.

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65 controls. Among other things, it states that “[e]very order granting an injunction and every restraining order must … describe in reasonable detail — and not by referring to the complaint or other document — the act or acts restrained or required.”

Makes sense. The persons subject to the order need to know what it is they can and can’t do.

In trademark infringement cases, one would think that would include a prohibition on infringing the plaintiff’s trademark. But that’s not specific enough. Nor is it enough direction to tell the defendant not to use trademarks that are “confusingly similar” to plaintiff’s trademarks.

That’s what the temporary restraining order said in Reno Air Racing Ass’n., Inc. v. McCord, 452 F.3d 1126 (9th Cir. 2006). It enjoined the defendant from “making, manufacturing, [or] distributing … any goods, packaging or any other items which bear the [plaintiff’s trademarks], or any confusingly similar variations thereof.” Indeed, that’s what a great many orders in trademark infringement cases say. But the Ninth Circuit rejected that language as too vague.

Reno Air serves as a good reminder for those drafting proposed injunctions, at least in the Ninth Circuit.

“Ultimately, there are no magic words that automatically run afoul of Rule 65(d), and the inquiry is context-specific. ‘[T]he fair notice requirement of Rule 65(d) must be applied ‘in the light of the circumstances surrounding [the order’s] entry.’ This case not only points out the pitfall of incorporating documents by reference in a TRO but also the hazard of failing to identify with particularity the enjoined conduct in conjunction with specific identification and description of the trademarks. The recipient of a TRO, which usually takes effect immediately, should not be left guessing as to what conduct is enjoined. The benchmark for clarity and fair notice is not lawyers and judges, who are schooled in the nuances of trademark law. The ‘specific terms’ and ‘reasonable detail’ mandated by Rule 65(d) should be understood by the lay person, who is the target of the injunction. This is a circumstance, among many in the legal field, that cries out for ‘plain English.’

“Here, the TRO was issued the same day the action commenced, and the parties had no prior litigation history. … [T]he TRO’s prohibition — i.e. enjoining infringement of ‘the trademarks set forth in Exhibit F … or any confusingly similar variations thereof’ — would certainly have left a lay person scratching his head in confusion. The TRO failed to meet even the most minimal fair notice requirement.”

These findings led the Ninth Circuit to find the order, as drafted (likely by the plaintiff’s attorney), was not enforceable. Not a good thing if you’re back in court trying to get an order of contempt against a noncomplying defendant.

The lesson when drafting a proposed injunction is to be specific and write in plain English — good drafting tips in almost any context.

A Strategy to Consider in Registering Trademarks on a Budget

A trademark owner wants to register two trademarks: a word mark, and a logo. But it only has a budget for one. Which one should it register?

The word mark, almost every time.

Getting a word mark registered will protect against confusingly similar uses of the word in all stylized and unstylized forms. In other words, if you register TRADEMARK in connection with bobsleds, you can probably enforce your rights against a seller who uses TRADEMURK in connection with sleds, saucers, and skis — regardless of how fanciful and different that seller’s depiction of its mark contrasts with yours.

That might not be the case if you instead register TRADEMARK as part of a red and green logo with lightning bolts emanating from the letters. In that case, a court could compare that form of TRADEMARK with a stylized form of TRADEMURK that’s orange and blue, surrounded by pink polka dots. Now, the similarities in the way the marks sound still make the marks at least somewhat similar — and the goods are still similar — but the striking difference in the marks’ visual appearance prevents it from being the slam-dunk case for confusing similarity that exists when you enforce your rights in the word mark alone.

If you have a logo that doesn’t contain your house mark — like Nike’s “Swoosh” — you need to protect that apart from your go-to word mark. Protection doesn’t require registration, but getting your mark registered (either at the state or federal level) gives you expanded rights that make it easier to keep copycats at bay.

Everyone’s on a budget. Being strategic in how you spend your marketing dollars in registering trademarks is a smart step in the right direction.

Kilts in a Twist: It's "Tilted Kilt" vs. "Twisted Kilt" in Trademark Showdown

Plaintiff’s four “Tilted Kilt” and logos (left) and

Plaintiff’s four “Tilted Kilt” and logos (left) and

defendants’ “Twisted Kilt” logo (far right)

It’s Tilted Kilt vs. Twisted Kilt.

Or at least it was.

In September, Tilted Kilt Franchise Ltd. Liability Co. filed a trademark lawsuit in the Western District against Brian Purdey and others alleged to own a new Irish pub in Puyallup called the “Twisted Kilt.”

Plaintiff alleged that defendants’ use of the “Twisted Kilt” name and a “Twisted Kilt” logo infringed plaintiff’s “Tilted Kilt” registered and common law word and design marks for restaurant and bar services, which plaintiff uses in connection with more than 50 U.S. pubs.

Twisted Kilt cried uncle. On Nov. 2, the court entered a stipulated judgment enjoining defendants from using “The Twisted Kilt Irish Pub & Eatery,” “The Twisted Kilt,” “Kilt Classic,” its “Twisted Kilt” logo, or any mark that is confusingly similar with Tilted Kilt’s word and design marks.

The stipulated judgement further prohibits defendants from ”[p]assing off their pub and eatery as ‘Twisted Kilt Irish Pub and Eatery’ or ‘Twisted Kilt’ or any food item as a ‘Kilt Classic’ or any business, product or service with a name using the word ‘kilt’ alone or in combination with any other elements.’”

The case cite is Tilted Kilt Franchise Ltd. Liability Co. v. Purdey, No. 11-5724 (W.D. Wash.).