Western District Denies Rose Art's Motion for Award of Fees Following Dismissal

In 2007, PlastWood SRL sued competing toy maker Rose Art Industries, Inc., in the Western District, alleging that many of the structures depicted on the packaging of Rose Art’s Magnetix-branded magnetic construction sets could not be built and collapse under their own weight. PlastWood also brought a Lanham Act claim based on the allegation that Rose Art advertised its toys as being safe for ages “3 to 100,” when in fact they were not.

The Western District granted Rose Art’s motions to dismiss and for summary judgment, ultimately finding that PlastWood did not have any evidence that Rose Art’s advertisement was literally false and that “‘no reasonable jury could conclude that the structures on the Magnetix box [could not] be built as represented on the box.’” (STL posts on the court’s orders on Rose Art’s motions to dismiss and for summary judgment here and here.)

After winning dismissal, Rose Art moved for an award of attorney’s fees on the ground that the case was “exceptional” under 15 U.S.C. § 1117(a). Cases are “exceptional” for purposes of awarding fees to the defendant where plaintiff’s claims are either “groundless, unreasonable, vexatious, or pursued in bad faith.” Cairns v. Franklin Mint Co., 292 F.3d 1139, 1156 (9th Cir. 2002).

On Feb. 4, Western District Judge James Robart rejected Rose Art’s motion. It concluded: “The court dismissed the age label claim early on in the case because the court determined that enforcing PlastWood’s allegations regarding safety labeling as a Lanham Act claim would be incongruent with the safety labeling requirements set forth by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (‘CPSC’). The court did not find the claim ‘baseless’; rather, it found that the claim was better addressed by the CPSC. The court granted summary judgment on the remaining Lanham Act claim after discovery and a number of expert reports revealed that the alleged collapsing structures could be built supporting Rose Art’s claim that its advertisements were not literally false. The court likewise does not find that this claim was a ‘baseless’ claim but rather a well-litigated claim that ultimately favored Rose Art.”

Nor was the court convinced that PlastWood engaged in a ‘blatant effort to capitalize on publicity relating to the tragic death of a child attributable to Rose Art,’ as Rose Art alleged in its motion.

The case cite is PlastWood SRL v. Rose Art Industries, Inc., No. 07-458 (W.D. Wash. Feb. 4, 2009) (Robart, J.).

Federal Circuit Reverses $8 Million False Advertising Award in Baden v. Molten

On Feb. 13, the Federal Circuit reversed Western District Judge Marsha Pechman’s denial of judgment as a matter of law in Baden Sports, Inc. v. Kabushiki Kaisha Molten, 541 F.Supp.2d 1151 (W.D. Wash. 2008), relating to the jury’s award of $8,054,579 for false advertising under Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act. (STL post on the jury’s award here.) Baden claimed that competing basketball maker Molten falsely advertised that its basketballs were “innovative.”

The Federal Circuit’s reversal was based on its application of Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 539 U.S. 23 (2003), to this claim.

It found: “We agree with Molten that Dastar precludes Baden’s section 43(a) claim. The Supreme Court stated in Dastar that section 43(a) of the Lanham Act does not have boundless application as a remedy for unfair trade practices. Because of its inherently limited wording, section 43(a) can never be a federal codification of the overall law of unfair competition, but can only apply to certain unfair trade practices prohibited by its text. Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act does not create liability from Molten’s advertisements because those advertisements do not concern the ‘origin of goods,’ to which section 43(a)(1)(A) is directed, nor do they concern the ‘nature, characteristics, [or] qualities’ of the goods, which is what Ninth Circuit law has interpreted Section 43(a)(1)(B) to address.”

Applying Dastar to Baden’s claim under section 43(a)(1)(A), the court determined it needed to evaluate whether “Molten’s advertising refers to the ‘producer of the tangible goods,’ in which case a claim under section 43(a)(1)(A) would be proper, or whether it refers to ‘the author of’ the idea or concept behind Molten’s basketballs, in which case the claim would be foreclosed by Dastar.

“Looking at the case in this light, it is apparent that Dastar does not permit Baden to claim false advertising under section 43(a)(1)(A). Baden has not argued that someone other than Molten produces the infringing basketballs, and nothing in the record indicates that Molten is not in fact the producer of the balls. Thus, Baden’s claims are not actionable under section 43(a)(1)(A) because they do not ‘cause confusion … as to the origin’ of the basketballs.”

With regard to Baden’s section 43(a)(1)(B) claim, the court found: “[W]e must not examine whether Baden’s false advertising claims otherwise implicate the nature, characteristics, or qualities of the basketballs. Thus, we must determine whether Baden has alleged anything more than false designation of authorship. We conclude that Baden has not. No physical or functional attributes of the basketballs are implied by Molten’s advertisements. ‘Innovative’ only indicates, at most, that its manufacturer created something new, or that the product is new, irrespective of who created it. In essence, Baden’s arguments in this case amount to an attempt to avoid the holding in Dastar by framing a claim based on false attribution of authorship as a misrepresentation of the nature, characteristics, and qualities of the goods.”

The court concluded that Baden’s claims “do not go to the ‘nature, characteristics, [or] qualities’ of the goods, and are therefore not actionable under section 43(a)(1)(B). To find otherwise, i.e., to allow Baden to proceed with a false advertising claim that is fundamentally about the origin of an idea, is contrary to the Ninth Circuit’s interpretation of Dastar.”

For these reasons, the court vacated the jury’s damages award based on Baden’s false advertising claims.

Interestingly, the court added that if it had applied the law of another circuit, such as the First Circuit, the case “may well have [had] a different result.”

The case cite is Baden Sports, Inc. v. Molten USA, Inc., Nos. 2008-1216, 2008-1246 (Fed. Cir. Feb. 13, 2008).

Hendrix Clan Settles Trademark Lawsuit; Plaintiffs Get Injunction and $3.2 Million

Does this mean the parties have made nice?

Probably not, but on Feb. 12, the Western District entered a stipulated Supplemental Judgment and Permanent Injunction ending the Hendrix family’s trademark dispute in Experience Hendrix, LLC, v. Electric Hendrix, LLC. Judge Thomas Zilly entered the order pursuant to the parties’ settlement and voluntary dismissal of Electric Hendrix’s Ninth Circuit appeal.

The settlement appears to give Janie Hendrix (the adopted daughter of Jimi’s Hendrix’s father) and the Hendrix family’s licensing company a total victory over the upstart vodka company owned in part by Leon Hendrix, Jimi’s brother.

STL’s discussed this case a lot, as it’s been one of the more exciting trademark fights around these parts in a while. (See posts on case highlights from March 7, 2007, Aug. 9, 2008, and September 9, 2008.)

In the end, the Electric Hendrix defendants agreed to judgment in favor of the Experience Hendrix plaintiffs, jointly and severally, in the amount of $3,200,000.

The Electric Hendrix defendants also agreed to be permanently enjoined from using, advertising, registering, applying to register, or challenging the validity of plaintiffs’ trademarks, including HENDRIX, AUTHENTIC HENDRIX, EXPERIENCE HENDRIX, and JIMI HENDRIX. The order also permanently enjoins the defendants from making any use of marks that are confusingly similar to the plaintiffs’ marks, and from selling any product that purports to have any connection with Jimi Hendrix, the plaintiffs, or the Hendrix family.

The parties apparently inked their settlement agreement in mediation on Dec. 29, 2008, before the Ninth Circuit decided Electric Hendrix’s appeal.

The case cite is Experience Hendrix, LLC v. Electric Hendrix, LLC, No. 07-338 (W.D. Wash.).

Seattle Times article on the case today. Wonder where it heard about the settlement?! No matter, I’ve got nothing but love for the local press — at least when it’s reporting on trademark issues.

Can Tort Theory Enable Plaintiff to Recover UDRP Filing Fees?

Here’s a novel legal theory:

Cybersquatter registers a domain name that infringes the trademark owned by Owner. Owner prevails in a UDRP arbitration and the panel transfers the domain name to Owner. Owner is as whole as the UDRP can make it. But Owner is out the (not insubstantial) amount it paid to file the complaint. Seeking to be made financially whole, Owner sues Cybersquatter in small claims court to recover its fee. But for Cybersquatter’s bad conduct, Owner argues, it never would have had to spend that money.

How’s the court rule?

Rockin' Perfume Tardemark Dispute Comes to Seattle

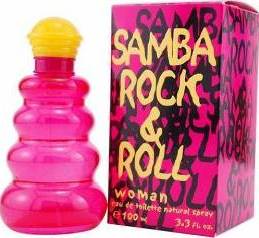

On Feb. 10, parfumerie Sportsfragrance, Inc., filed suit in the Western District against competitor The Perfumer’s Workshop International, Ltd. Plaintiff claims defendant’s sale of ROCK & ROLL branded or named perfrume infringes plaintiff’s registered ROCK ‘N ROLL trademark for fragrances and constitutes the sale of counterfeit goods. Defendant sells its SAMBA ROCK ‘N ROLL eau de toilette spray at Target and other retailers.

While plaintiff’s mark is indeed registered, I could not immediately find any examples of its actual use of the mark in connection with fragrances. For what it’s worth, I found Sports Fragrance-branded APRIL SHOWERS, HERO, BELOVED VANILLA, DAYDREAM, and GOLDEN AUTUMN perfumes, but no ROCK ‘N ROLL. We’ll see if defendant asserts an abandonment defense.

The case cite is Sportsfragrance, Inc. v. The Perfumer’s Workshop, International, Ltd., No. 09-177 (W.D. Wash.).