Golf App Maker Sues U.S. Golf Association in Seattle for Unfair Competition

Screen shot from Diablo Golf iPhone app

Screen shot from Diablo Golf iPhone app

XYZ Media, Inc., is a Bellingham-based company that develops Web sites and apps for smart phones. It publishes www.DiabloGolf.com, a social networking Web site for golfers, and an app by the same name. XYZ’s site and app stores a golfer’s scores, courses played, slope ratings, course ratings, and enables users to calculate course handicaps.

The U.S. Golf Association (USGA) provides goods and services to golfers and golf courses. The USGA claims to own common law or registered trademarks in HANDICAP INDEX, COURSE HANDICAP, SLOPE, and COURSE RATINGS in connection with golf.

On June 8, XYZ filed suit against the USGA in the Western District of Washington. The lawsuit claims the USGA wrongly terminated XYZ’s access to USGA data used in the Diablo Golf Website and app in an effort to convert users to USGA’s competing product. XYZ also claims the USGA falsely told Apple that XYZ was not authorized to create iPhone apps using USGA’s data, and threatened suit based on XYZ’s use of the terms “handicap index,” “course handicap,” “slope,” and “course ratings,” which XYZ says are generic and/or functional.

XYZ seeks damages and injunctive relief, as well as declarations of noninfringement. It also seeks to cancel the USGA’s federal trademark registrations.

The suit makes similar claims against the Washington Golf Association.

Defendants have not yet answered the complaint.

The case cite is XYZ Media, Inc. v. United States Golf Association, No. 12-989 (W.D. Wash.).

Ninth Circuit Reverses Functionality Finding for Skull-Shaped Vodka Bottle

Globefill’s trade dress: Not functional, the Ninth Circuit says

Globefill’s trade dress: Not functional, the Ninth Circuit says

Plaintiff Globefill Incorporated makes booze. So does defendant Elements Spirits, Inc.

In 2010, Globefill sued Elements in the Central District of California for trade dress infringement.

It described its trade dress in connection with its crystal head vodka as “a bottle in the shape of a human skull, including the skull itself, eye sockets, cheek bones, a jaw bone, a nose socket, and teeth, and including a pour spout on the top thereof.”

The Central District of California dismissed Globefill’s claim on grounds of functionality.

On May 23, the Ninth Circuit reversed, finding the skull design was purely ornamental.

“We typically consider four factors in determining whether a product feature is functional: ‘(1) whether the design yields a utilitarian advantage, (2) whether alternative designs are available, (3) whether advertising touts the utilitarian advantages of the design, (4) and whether the particular design results from a comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture.’ Disc Golf Ass’n, Inc. v. Champion Discs, Inc., 158 F.3d 1002, 1006 (9th Cir. 1998).”

Applying these factors, the court found “the trade dress elements Globefill described in its operative complaint cannot be said to be functional as a matter of law. The skull design is ornamental and serves no utilitarian purpose; alternative bottle designs are available in abundance; and using the design increases, rather than decreases, Globefill’s manufacturing and shipping costs.”

Therefore, it found the trade dress was not functional and reversed.

The case cite is Globefill Inc. v. Elements Spirits, Inc., No. 10-56895, 2012 WL 1868861 (9th Cir. May 23, 2012).

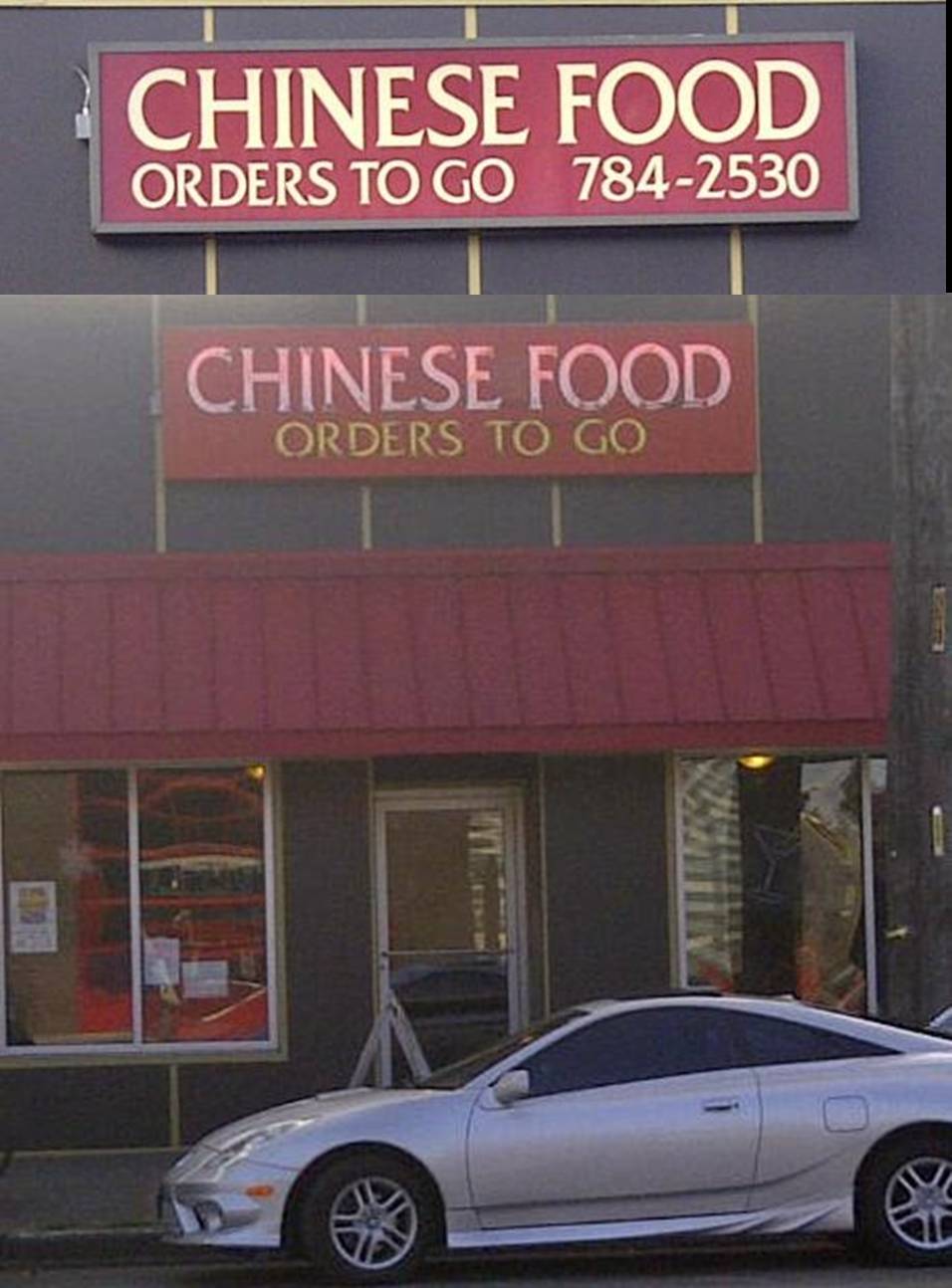

"Chinese Restaurant" New Winner of Seattle's Most Generic Trademark?

A new winner in the category of Seattle’s Most Generic Trademark?

A new winner in the category of Seattle’s Most Generic Trademark?

Signs advertising “Chinese Restaurant”

in Seattle’s Phinney Ridge neighborhood (Photos by STL)

Spotting generic trademarks is a bit of a sport at STL (see posts here, here, and here).

We’ve found some good ones over the years, but for a minute it looked like we could crown a new champ: CHINESE RESTAURANT for a Chinese restaurant located in Seattle’s Phinney Ridge neighborhood.

At least that’s what its signs say.

Unfortunately, after further investigation, we’ve determined the establishment actually has a name: Greenwood Mandarin Restaurant. Not a terribly distinctive name — given that it’s located on Greenwood Avenue — but still a sizable step up from CHINESE RESTAURANT.

Guess we’ll have to keep looking for a new champ.

Brands Represent Companies' Reputations. And They're Worth Billions.

GeekWire and others today reported on a new global brand value study.

Seattle companies did well. Microsoft ranked fifth ($76.6B). Amazon was 18th ($34.077B).

Both were down over last year.

That’s interesting, but to me the real story is how valuable brands are. An intangible icon worth $76.6 billion?! How amazing is that?! And the mere act of putting the Amazon name on the functional equivalent of Amazon’s business increases its value by by more than $34 billion.

That’s the power of trademarks. These companies have built incredible reputations. They’re trusted, even admired. They’re handsomely rewarded by consumers for delivering on countless promises. And they should be. Hopefully their return on investment will encourage them to keep doing so for years to come. What shouldn’t be lost is the fact they have the trademark to thank for enabling happy consumers to come back for more.

Worldwide top 100 most valuable brands here. Study author MillardBrown’s news release with commentary here.

Ninth Circuit Sides with FDCA over Lanham Act in False Advertising Claim

The Lanham Act governs false advertising, including information contained on a product’s label.

The Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act governs governs information contained on a product’s label when the product involves food, drugs, or cosmetics.

So which statute applies when they overlap and the standards conflict?

The Ninth Circuit addressed that question on May 17, when it decided Pom Wonderful LLC’s claim that Coca-Cola Co.’s “Pomegranate Blueberry” drink was deceptively named and labeled when the product consists of 99.4% apple and grape juices, and only 0.3% pomegranate juice and 0.2% blueberry juice. (The remaining 0.1% consists of raspberry juice.)

Pom asserted a claim under the Lanham Act. Coca-Cola responded that the FDCA preempts the Lanham Act because it comprehensively regulates the labeling of food.

The Ninth Circuit agreed with Coca-Cola.

“In concluding that Pom’s claim is barred, we do not hold that Coca-Cola’s label is non-deceptive,” the court found. “Pom contends that the words ‘Pomegranate Blueberry’ appear in larger, more conspicuous type on Coca-Cola’s label than do the words ‘Flavored Blend of 5 Juices.’ If the FDA believes that this context misleads consumers, it can act. But the FDA has apparently not taken a view on whether Coca-Cola’s labeling misleads consumers — even though it has acted extensively and carefully in this field. (The FDA has not established a general mechanism to review juice beverage labels before they reach consumers, but the agency may act if it believes that a label in the market is deceptive.) As best we can tell, Coca-Cola’s label abides by the requirements the FDA has established. We therefore accept that Coca-Cola’s label presumptively complies with the relevant FDA regulations and thus accords with the judgments the FDA has so far made. Out of respect for the statutory and regulatory scheme before us, we decline to allow the FDA’s judgments to be disturbed.

“We do not suggest that mere compliance with the FDCA or with FDA regulations will always (or will even generally) insulate a defendant from Lanham Act liability. We are primarily guided in our decision not by Coca-Cola’s apparent compliance with FDA regulations but by Congress’s decision to entrust matters of juice beverage labeling to the FDA and by the FDA’s comprehensive regulation of that labeling. To give as much effect to Congress’s will as possible, we must respect the FDA’s apparent decision not to impose the requirements urged by Pom. And we must keep in mind that we lack the FDA’s expertise in guarding against deception in the context of juice beverage labeling. In the circumstances here, ‘the appropriate forum for [Pom’s] complaints is the [FDA].’”

The case cite is Pom Wonderful LLC v. Coca-Cola Co., __ F.3d. __, 2012 WL 1739704, No. 10-55861 (9th Cir. May 17, 2012).