Patent and Trademark Office Offers Excellent Trademark Resources

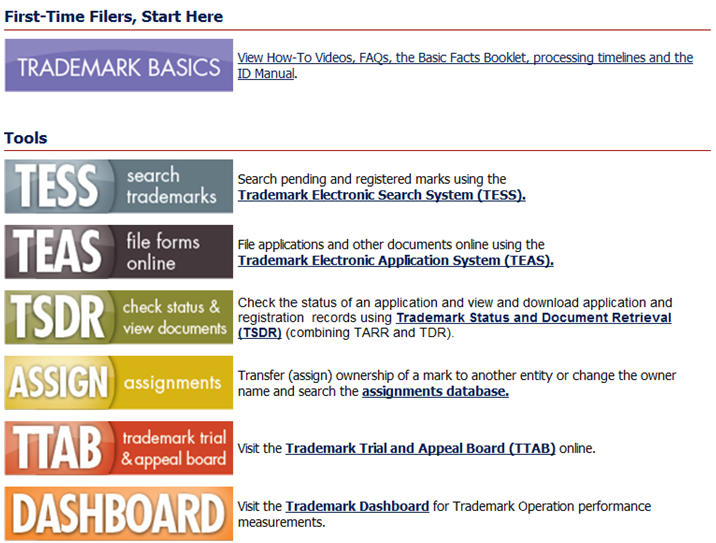

Screen shot from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s Web site

Screen shot from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s Web site

The PTO has some excellent resources for learning about trademark law. Videos, even. They’re all free and are collected here.

My favorite tool is the Trademark Electronic Search System (TESS) database. I use it constantly. It’s accessible here.

Click the “Basic Word Mark Search (New User)” hyperlink, click the “Live” radio button, type the desired trademark into the search box, and click the “Submit Query” button. The results will give you hyperlinks to all pending trademark applications and registrations in the PTO’s system. The hyperlinked pages provide basic information about each trademark — the owner, the associated goods and services, the application date, etc. And best of all, you can drill down further from that page by clicking the blue “TDR” button, which provides links to the various documents in the application file — from application to registration certificate. It’s an invaluable tool that I use every day.

The database has its limitations. For example, it doesn’t provide information about a party’s use of the trademark, and you must include confusingly similar trademarks in your search for the results to be meaningful. But it’s a heck of a resource that shouldn’t be limited to trademark attorneys. Anyone can use it, and they should.

LifeWise Sues Regence Life Over Switch to "LifeMap" Trademark

Time will tell whether LifeWise’s trademark infringement lawsuit will be

Time will tell whether LifeWise’s trademark infringement lawsuit will be

“boringly good.” (Screen shot from LifeWise’s Web site)

Health insurer LifeWise has sued competing health insurer Regence Life for trademark infringement.

LifeWise Assurance Co. and affiliates claim Regence Life and Health Insurance Co.’s adoption of LIFEMAP infringes their LIFEWISE registered trademarks.

Both health insurers do business in Washington and Oregon.

LifeWise filed suit after Regence Life allegedly changed its name to “LifeMap Assurance Company” and its house brand name to LIFEMAP. The change allegedly occurred on April 1.

“The new corporate and brand names represent an obvious and intentional copy of the ‘LifeWise Assurance Company®’ and ‘LifeWise®’ servicemarks, and are confusingly similar to the LifeWise® branded products and services offered by Plaintiffs,” the complaint alleges.

LifeWise filed suit on April 4. Regence Life has not yet filed its answer.

The case cite is LifeWise Assurance Co. v. Regence Life and Health Insurance Co., No. 12-00568 (W.D. Wash.).

Fourth Circuit Vacates Most of Flawed Keyword Advertising Decision

Big keyword advertising decision today: the Fourth Circuit decided Rosetta Stone v. Google.

The court did the right thing. It vacated the district court’s exceedingly Google-friendly decision incorporating sloppy analysis and incorrect application of trademark law, and remanded for the Eastern District of Virginia to reconsider the case in light of proper standards.

In the end, I think the result will be the same — on re-examination, Google won’t be directly or indirectly liable for counterfeiters’ purchase of Rosetta Stone’s trademark as a search engine keyword. But this time, the analysis won’t be tortured and misleading.

For example, the district court found Google wasn’t liable for selling Rosetta Stone’s trademark as a keyword because its use of the mark was functional. That finding stood the functionality doctrine on its ear. The proper place for functionality analysis is to examine the plaintiff’s trademark (or, more commonly, trade dress) for whether it serves a useful purpose. (A trademark isn’t protectable as a trademark if it serves a useful purpose other than identifying the product’s source.) The district court instead examined the defendant’s use of the trademark, which was strange, wrong, and not helpful.

The Fourth Circuit left no room for the district court to get it wrong on remand.

“The functionality doctrine simply does not apply in these circumstances. The functionality analysis below was focused on whether Rosetta Stone’s mark made Google’s more product more useful, neglecting to consider whether the mark was functional as Rosetta Stone used it. Rosetta Stone uses its registered mark as a classic source identifier in connection with its language learning products. Clearly, there is nothing functional about Rosetta Stone’s use of its own mark; use of the words ‘Rosetta Stone’ is not essential for the functioning of its language-learning products, which would operate no differently if Rosetta Stone had branded its product ‘SPHINX’ instead of ROSETTA STONE. Once it is determined that the product feature — the word mark ROSETTA STONE in this case — is not functional, then the functionality doctrine has no application, and it is irrelevant whether Google’s computer program functions better by use of Rosetta Stone’s nonfunctional mark.

“As the case progresses on remand, Google may well be able to establish that its use of Rosetta Stone’s marks in its AdWords program is not an infringing use of such marks; however, Google will not be able to do so based on the functionality doctrine. The doctrine does not apply here, and we reject it as a possible affirmative defense for Google.”

The Fourth Circuit similarly vacated the district court’s dismissal of Rosetta Stone’s claims for direct trademark infringement, contributory trademark infringement, and dilution. It affirmed the district court’s dismissal of Rosetta Stone’s claims for vicarious trademark infringement and unjust enrichment.

The decision is what I had expected, and what I had hoped for. It requires district courts to apply trademark principles with rigor and gives the non-moving party on summary judgment the benefit of the reasonable inferences that can be drawn from the evidence presented, in accordance with established summary judgment principles.

The case cite is Rosetta Stone Ltd. v .Google, Inc., No. 10-2007 (4th Cir. April 9, 2012).

Associated Press Uses "iPad" to Discuss the Issue of Generic Trademarks

A Xerox ad asking consumers not to use its brand as a generic

substitute for “copy machine.” (STL post on the ad here.)

The Associated Press ran a good story this weekend about the possibility and ramifications of “iPad” becoming a generic synonym for “tablet.”

I was fortunate enough to lend a quote about the struggle famous brand owners face in wanting their brand to become widely adopted — but not so widely adopted that it becomes generic. “Marketing people want the brand name as widespread as possible and trademark lawyers worry … the brand will lose all trademark significance.”

The story does a nice job of explaining why brand owners sometimes are put in the uncomfortable position of trying to persuade consumers not only to purchase their products, but also not to use their brand in a way the company doesn’t like — as Xerox has done with its branded copy machines.

In the end, I’m not too concerned for Apple. It was right to give the public a generic word to refer to the class of goods in which its product competes: tablets. Perhaps for that reason alone, I don’t see anyone referring to an Amazon Fire tablet as an Amazon Fire “iPad” anytime soon. Still, the article does as good a job as I’ve seen explaining why genericide matters to famous brand owners.

T-Shirt and Coffee Mug Sellers Take Note: A Trademark Must Indicate Source

A saying needs to indicate source to be protected as a trademark

A saying needs to indicate source to be protected as a trademark

This may sound a little circular, but to be protected as a trademark, the word or symbol at issue needs to function as a trademark. That means it has to tell the consuming public that the good or service you sell in connection with the trademark comes from you.

A common pitfall is the ornamental use of a word or symbol. Let’s say you have a cool design or catchy saying, so you decide to put it on t-shirts and coffee mugs. That’s great, but it’s tricky protecting your words or design in that context as a trademark. Unless, of course, they actually function as a trademark by indicating source.

Think about where a brand appears on a t-shirt or coffee mug. On a shirt, it’s often on the inside tag or on a hang tag that’s attached to a shirt before it’s sold. On a coffee mug it’s usually on the side or even on the bottom. In both cases, the brand — the signal to customers who made the shirt or cup — takes a back seat to the catchy words or cool design that likely motivated the customer to purchase the item. If you want to protect those words or design as a trademark, you need to make sure they’re also displayed where the brand usually appears. As long as the words or design tell customers who made the good, it’s protectable as a trademark. Otherwise, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office won’t register it, and a court won’t enforce trademark rights in it.

If your cool design or catchy saying doesn’t indicate source, you still might be able to protect it through copyright law or by getting a design patent — but that’s often a stretch. But one thing should be clear: you can’t protect it under trademark law if it’s just a decoration.