Ninth Circuit Affirms False Advertising Finding Against Skydiving Marketer

Skydive Arizona, Inc., has sold skydiving services under its SKYDIVE ARIZONA trademark since 1986.

Cary Quattrocchi, Ben Butler, and others, d/b/a 1800SkyRide (“Skyride”), operate an advertising service that makes skydiving arrangements for customers and issues certificates that can be redeemed at a number of skydiving drop zones.

Skydive Arizona sued Skyride in the District of Arizona for false advertising, trademark infringement, and cybersquatting. On its false advertising claim, it alleged that Skyride misled consumers wanting to skydive in Arizona by stating that Skyride owned skydiving facilities in Arizona when it did not. It also alleged that Skyride deceived consumers into believing that Skydive Arizona would accept Skyride’s skydiving certificates when it would not.

Following partial summary judgment and a trial, a jury awarded Skydive Arizona $1 million in actual damages for false advertising, $2.5 million in actual damages for trademark infringement, $2,500,004 in profits resulting from the trademark infringement, and $600,000 for statutory cybersquatting damages.

Skyride appealed the court’s finding of liability for false advertising on summary judgment on the ground its false statements were not material to consumers’ purchasing decisions. In particular, Skyride argued that customer James Flynn’s declaration that supported the materiality element was ambiguous and fell short of survey evidence that courts often accept as proof.

The Ninth Circuit wasn’t convinced. “Skydive Arizona’s decision to proffer declaration testimony instead of consumer surveys to prove materiality does not undermine its motion for partial summary judgment. Although a consumer survey could also have proven materiality in this case, we decline to hold that it was the only way to prove materiality. Indeed, as we held in Southland Sod [Farms v. Stover Seed Co., 108 F.3d 1134, 1140 (9th Cir.1997)], consumer surveys tend to be most powerful when used in dealing with deceptive advertising that is ‘literally true but misleading.’ Here, Defendants’ advertisements were both misleading and false. Flynn’s declaration proved that consumers had been actually confused by SKYRIDE’s websites and advertising representations. The district court’s materiality finding was further supported by Skydive Arizona’s evidence of numerous consumers who telephoned or came to Skydive Arizona’s facility after having been deceived into believing there was an affiliation between Skydive Arizona and SKYRIDE.”

The case cite is Skydive Arizona, Inc. v. Quattrocchi, __ F.3d. __, No. 10-16196, 2012 WL 763545 (9th Cir. Mar. 12, 2012).

Court Denies Preliminary Injunction in Trademark Case about Infant Pillows

Plaintiff AR Pillow, Inc., makes pillows designed to reduce acid reflux in infants.

Defendant Annette Cottrell owns pollywogbaby.com, is a former distributor of plaintiff’s pillows, and sells pillows that compete with plaintiff’s pillows.

Plaintiff sued Ms. Cottrell for trademark infringement, unfair competition, and defamation arising out of her use of plaintiff’s AR PILLOW trademark on her Web site along with the statements that she had “chosen to discontinue the product” and that the plaintiff’s pillow requires babies to bend their legs, which AR Pillow claims is false.

Plaintiff moved for a temporary restraining order or preliminary injunction seeking to stop such use.

On March 13, Western District Judge Richard Jones denied the motion, finding AR Pillow was not likely to succeed on the merits of its trademark infringement claim. In short, the court found there wasn’t much in Ms. Cottrell’s Web site that was likely to cause confusion with plaintiff’s trademark.

For example, on the “actual confusion” likelihood of confusion factor, the court noted: “Here, plaintiffs argue that there is evidence that at least one customer was actually confused by defendant’s use of the mark on her website. Plaintiffs allege that they ‘received a call from a customer seeking to cancel an order from an AR Pillow from pollywogbaby.com.’ Nothing in this allegation suggests that the customer was confused. Rather, it suggests that she was not confused because she knew that AR Pillow was different than pollywogbaby.com. Receiving unfavorable information about a product is not the same as consumer confusion.”

The case cite is AR Pillow Inc. v. Cottrell, No. 11-1962 (W.D. Wash. March 13, 2012) (Jones, J.).

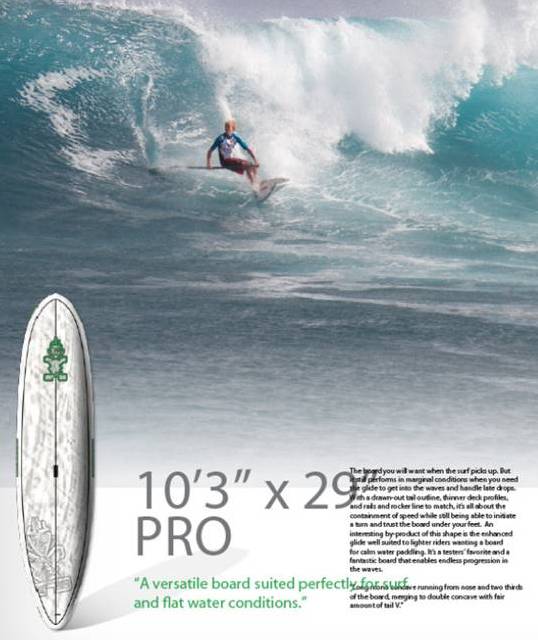

False Advertising Claim Over Surf Boards Rides Litigation Wave to Seattle

Whose board is it, anyway?

Whose board is it, anyway?

The catalog photo plaintiffs say defendants altered

A false advertising claim over competing stand-up paddle boards has ridden the litigation wave all the way to Seattle.

On March 9, plaintiffs Jimmy Lewis and Fuacata Sports LLC filed suit against competitors Trident Performance Sports Inc. and Starboard World Limited, alleging that defendants included a photo in their catalog showing one of plaintiffs’ custom, high-performance boards in competition — altered, so it appers to depict one of defendants’ production boards.

Plaintiffs’ complaint states that “[d]efendant Starboard World Limited created a 2011 Starboard SUP [Stand Up Paddleboard] product catalogue which incorporates a picture of a Starboard-sponsored athlete riding a Jimmy Lewis custom ‘gun’ board in extremely challenging Maui surf conditions. This photograph was placed on the same page as the Starboard Pro Wave ‘gun’ board, which was a new edition to the Starboard SUP product line. The photograph, found on page 52 of the 2011 Starboard SUP catalogue, was digitally altered to add Starboard Pro Wave pin [striping], carbon brush markings and a faint impression of the Starboard logo in order to lead consumers to believe the Jimmy Lewis custom board was the 2011 Starboard Pro Wave board. The depicted board was undeniably custom made by Jimmy Lewis and delivered as a blank board to the Starboard team rider.”

The complaint alleges that defendants used a similar photo in a national advertising campaign as well.

Plaintiffs allege defendants’ acts amount to “reverse passing off,” a legal theory in which the defendant “passes off” the plaintiff’s product as its own.

Defendants have not yet answered plaintiffs’ complaint.

The case cite is Jimmy Lewis v. Trident Performance Sports, Inc., No. 12-415 (W.D. Wash.).

Western District Finds Song Title Generic, Dismisses Trademark Claim

The song title “Mom Song” isn’t protectable as a trademark, Western District Judge Ricardo Martinez found last month.

He granted summary judgment in favor of comedian Anita Renfroe, who moved to dismiss comedian Frank Coble’s false designation of origin claim alleging that Ms. Renfroe’s “Momisms Song” about mothers infringed rights in his “Mom Song” about mothers.

The court found: “Mom Song’ is a generic mark that is not protectable. Indeed, virtually any song regarding the broad topic of motherhood could appropriately bear the same mark. The ‘Mom Song’ mark, which simply names the product to which it is attached, does not require ‘the exercise of some imagination … to associate [the] mark with the product,’ and, although the mark is descriptive in the most literal sense, the primary significance of the mark is to describe the type of product (i.e., a song about a mom) rather than its producer. Because the term ‘Mom Song’ ‘embrace[s] an entire class of products’ (i.e., songs about moms), it can receive no trademark protection. Allowing trademark protection for such a generic phrase would place an undue burden on competition, contrary to the goals of trademark law.”

The court also dismissed Mr. Coble’s claim for copyright infringement.

The case cite is Coble v. Renfroe, No. 11-0498, 2012 WL 503860 (W.D. Wash. Feb. 15, 2012) (Martinez, J.).

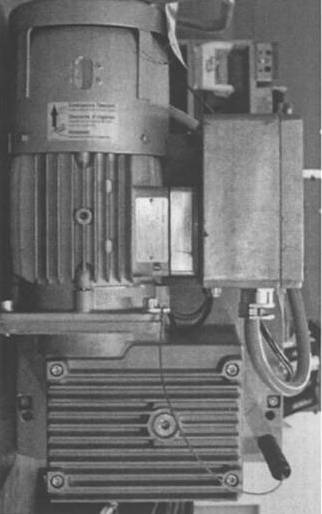

Different Look Didn't Turn Functional Design into Protectable Trade Dress

Protectable trade dress? Not even close, the Ninth Circuit finds

Protectable trade dress? Not even close, the Ninth Circuit finds

It doesn’t happen terribly often.

In fact, I don’t think it happens nearly enough. Awarding the prevailing party attorney’s fees in a trademark case, that is.

But that’s what happened in Secalt S.A. v. Wuxi Shenxi Const. Mach. Co., Ltd., 668 F.3d 677 (9th Cir. 2012), where plaintiffs claimed trade dress protection in their industrial-strength traction hoist.

Plaintiffs Secalt, S.A., and Tractel, Inc. (“Tractel”), argued the overall exterior appearance of their hoist is nonfunctional because the hoist’s design—wherein the component parts meet each other at right angles—provide a distinctive “cubist” look and feel.

Tractel claimed its trade dress consisted of: “1) a cube-shaped gear box with horizontal fins; 2) a cylindrical motor mounted in an off-set position on the cube and partially overhanging the edge of the cube; 3) the cylindrical motor including vertical fins on a lower portion and a generally smooth sheet metal upper cover having a control descent lever and top cap positioned over the upper end and supported by rectangular legs; 4) a rectangular control box cantilevered to the motor by a square shaped member, the control box positioned over the cube, the control box including controls thereon; and 5) a rectangular frame.”

As evidence that these features aren’t functional, Tractel argued they were protected by a third party’s design patent.

The District of Nevada, however, didn’t buy the idea that the subject features weren’t functional. It granted summary judgment for the defendant and awarded attorney’s fees as an “exceptional” case.

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit found Tractel didn’t seem to understand that functional features can’t be protected under trade dress law simply because they are different than what the competition offers.

It wrote: “Tractel’s fundamental misunderstanding—which infects its entire argument—is that the presumption of functionality can be overcome on the basis that its product is visually distinguishable from competing products. While such distinctive appearance is necessary, it is here insufficient to warrant trade dress protection.”

It found that “[e]xcept for conclusory, self-serving statements, Tractel provides no other evidence of fanciful design or arbitrariness; instead, here, ‘the whole is nothing other than the assemblage of functional parts, and where even the arrangement and combination of the parts is designed to result in superior performance, it is semantic trickery to say that there is still some sort of separate ‘overall appearance’ which is non-functional.’”

Interestingly, the court did not find that Tractel acted in bad faith. Yet, the lack of bad faith didn’t save Tractel from an award of attorney’s fees.

“Although Tractel does not ultimately prevail, were it able to provide some legitimate evidence of nonfunctionality, this case would likely fall on the unexceptional side of the dividing line. When summary judgment motions were heard, the parties had been in discovery for almost two years, taken multiple depositions, and compiled substantial documents. Yet, Tractel could not identify the aesthetic value of the exterior design, and was reduced to arguing that it was pursuing a ‘cubist’ look and feel even though its own witnesses undercut this argument.”

The court concluded that “Tractel’s action appears to be a conscious, albeit misguided, attempt to assert trade dress rights in a non-protectable machine configuration.” On that ground, it affirmed the district court’s judgment and upheld the award of attorney’s fees to the tune of $836,899.99. (The court also upheld the district court’s finding that the rates defense counsel charged — $320 to $685 per hour in 2010 — were “reasonable.”)

Las Vegas Trademark Attorney’s discussion of its home-grown case here.