Entries by Michael Atkins (1064)

China's Chief Justice Discusses China IP Law at Microsoft Symposium

Here’s one more post from last week’s excellent symposium on “Trademark Law and Its Challenges in 2011” (previous post on Prof. Tom McCarthy’s keynote speech here).

The program opened with an introduction to Chinese IP law from none other than Judge Kong Xiangjun (left), Chief Justice of the Intellectual Property Tribunal of China’s Supreme Court. That’s the highest court handling civil IP cases. Suffice it to say, Judge Kong represented quite an authority to provide such a briefing.

The program opened with an introduction to Chinese IP law from none other than Judge Kong Xiangjun (left), Chief Justice of the Intellectual Property Tribunal of China’s Supreme Court. That’s the highest court handling civil IP cases. Suffice it to say, Judge Kong represented quite an authority to provide such a briefing.

Here are a few things I learned:

- China’s civil system is a bit different than ours. Two trials are standard. The first starts at a given level of authority, with a second trial at a higher level, which provides the binding decision. The complexity and amount in controversy determine which level hears the first trial. An unhappy litigant can appeal the second court’s decision. Each case is decided by at least three judges.

- The IP Tribunal handles both second trial cases and retrial cases. Each year, it hears approximately 10 second-trial cases and more than 300 retrial cases.

- The number of IP cases in China has increased dramatically. From 2009 to 2010, the percentage of IP cases increased by 36.3%. Copyright cases make up half the case load. Each year, the court hears 7,000 trademark and 8,000 patent cases. It also decides cases involving antitrust and unfair competition.

- Only 5% of China’s IP cases involve foreign companies, most of which involve a foreign entity suing a Chinese entity, though there are increasing cases of Chinese entities suing foreign entities. Most IP cases involve disputes between Chinese companies.

- The volume of trademark registrations has increased. Indeed, the increase is probably the world’s largest. China also sees more trademark disputes each year, which corresponds with its increased protection of marks.

- Chinese lawyers, academics, and those in industry have begun discussing the need to revise China’s trademark laws again. Such laws have been revised three times since the 1980s.

- One thing revisions would seek to improve is the length of time needed to register a trademark. There is a big backlog of applications, which causes complaints. China wants a simpler and more efficient system for registering marks.

- China believes it has a problem with malicious individuals who preempt the registration of third parties’ trademarks. People want that to change.

- People are also talking about increasing trademark protection. Currently, it’s hard to prove plaintiffs’ damages and defendants’ profits. People are calling for a stipulated amount of damages to further protect trademarks.

- These issues are still in discussion. It’s unclear how or whether revisions will be made.

Photo credit: China Daily

Prof. McCarthy: "Avoid Extremes" in Trademark Enforcement Efforts

On Feb. 3, I had the pleasure of attending a fantastic program sponsored by the University of San Francisco School of Law’s McCarthy Institute and Microsoft Corp. entitled, “Trademark Law and Its Challenges in 2011” (brochure here; World Trademark Review Blog summary of the event here).

On Feb. 3, I had the pleasure of attending a fantastic program sponsored by the University of San Francisco School of Law’s McCarthy Institute and Microsoft Corp. entitled, “Trademark Law and Its Challenges in 2011” (brochure here; World Trademark Review Blog summary of the event here).

One highlight was meeting J. Thomas McCarthy (photo above), author of the encyclopedic “McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition,” a treatise that’s familiar to trademark practitioners everywhere.

Prof. McCarthy gave the keynote address on the issue of trademark bullies, answering the question, “When Should Trademark Owners Threaten Suit?”

After recounting examples of what some would cite as over-zealous trademark protection — including Monster Cable’s effort to enforce its trademark rights against a “Monster” mini-golf course depicting monsters — Prof. McCarthy argued that trademark lawyers should ensure enforcement efforts on behalf of their clients are appropriate for each situation.

Following paraphrases excerpts from Prof. McCarthy’s speech. I took notes as best I could, but I certainly did not catch every word. For that reason, I’m not using quotation marks, though I’ve tried to capture Prof. McCarthy’s message. It’s a good one.

*****

What most trademark lawyers worry about is the downside risk of being too lax in their enforcement efforts. They don’t seem to worry about over-reaching. Some are proud to be bullies, as it sends the message that “We’re tough; don’t even think about infringing. Once we shoot a few hostages, everybody will get the message.”

But there’s a downside to over-reaching. One is in Internet shaming campaigns against the over-reaching brand owner. Trademark lawyers should look beyond statutes and cases. Consumers think of themselves in terms of what they consume. Thousands of people on the Internet are ready to throw stones at companies they think are acting like a trademark bully. The reputation of a company can take a hit.

The key to a balanced trademark enforcement program is to avoid extremes. Only rarely does a trademark owner risk losing rights in its mark. The real risk is in losing the mark’s strength. Also laches, but courts understand that laches doesn’t require a trademark owner to object and sue all potential infringers.

Overly-aggressive enforcement measures can backfire, resulting in loss of goodwill and embarrassment to the trademark owner. An overly-aggressive trademark owner has two choices: it can carry out its threats of suit by bringing fringe suits, which can result in unfavorable court decisions or, in extreme cases, liability for abuse of process or for violating Rule 11. That really hurts the strength of the mark.

If an overly-aggressive owner instead bluffs — sends cease-and-desist letters but does not carry out its threats of suit — that will come out one day in discovery. In that case, the trademark owner is on record that each instance is a serious infringement. That kind of bluffing and not suing can hurt the owner’s ability to enforce its mark.

Not all cease-and-desist letters need to say the same thing. They don’t all need to instill shock and awe. Think about results. Overbearing letters will get posted on the Internet and will be part of a shaming campaign. Think of the Goldilocks rule: not too easy and soft, and not too hard and severe.

There are dangers in both directions. Attorneys should sit down with their clients’ decision-makers and see what plans exist for expansion in the future. Why should Monster Cable care about Monster Mini Golf? Lots of famous marks coexist peacefully, so there is no need to police all uses. Follow the Goldilocks rule and like Goldilocks, you will live happily ever after.

Photo credit: University of San Francisco School of Law

Not on Infringement Safari: Dakine's Reference to the Rainier Beer Logo

Rainier Beer’s logo and Dakine’s design

Rainier Beer’s logo and Dakine’s design

I went downhill skiing for the first time today.

Woo hoo! I’m hooked. I fell a ton, and my excursion was to what amounted to a bunny hill, but it was a lot of fun!

Ok, enough about me.

Yesterday, I was at an outdoor equipment store getting gear for my trip. I came across something worth mentioning here — a tool for snowboarders that depicted what looked an awful lot like the beloved Rainier Beer logo.

The first thing that struck me was I wasn’t on infringement safari. I wasn’t in a foreign land when I stumbled on this appropriation of a well-known trademark. This was a reputable store selling high-end merchandise from reputable sellers like Dakine, the one selling the “board plate” that called to mind the Rainier Beer design. You don’t spot potential trademark issues in that context every day.

Snowboarders are an irreverent bunch, or so I’ve heard. So they might think calling to mind a beer maker’s logo is desirable. But I’d think others would wonder why a maker of quality equipment would want to trigger thought about an unrelated company’s logo. Isn’t that a little distracting? And amateurish? I suppose that could be part of the allure.

My other impulse was to question whether this use was problematic at all. It probably wouldn’t constitute trademark infringement, since I doubt purchasers would think the maker of Rainier Beer (now Pabst Brewing Co.) had gotten into the business of selling snowboard accessories. (A closer case would be for consumers to wonder whether Pabst licensed the logo or consented to its distorted use.) Dilution probably would be Pabst’s best tool, but I wonder if the Rainier Beer logo — quite well known in Seattle, where the beer used to be brewed — is famous on a nationwide basis, the statutory threshold for dilution protection under the Trademark Dilution Revision Act. I doubt it.

So where would that leave Pabst? Assuming it objected to Dakine’s use, its best bet would seem to be a claim for state law dilution, such as under Washington’s Trademark Act. Its logo almost certainly is famous here, so it probably would garner such protection.

I doubt a court would view Dakine’s use as protectable parody, since it doesn’t simultaneously call to mind the thing being parodied and comment on that thing.

I suppose Pabst may have ok’d Dakine’s use on the theory that it’s free advertising and is beneficial for its beer to be associated with a quality seller to the snowboarding set.

I don’t know, but these things are interesting to think about when not fearing for one’s life on the slopes.

Joyous Trademark Dispute Pits "Sweet Bliss" Against "Bliss"

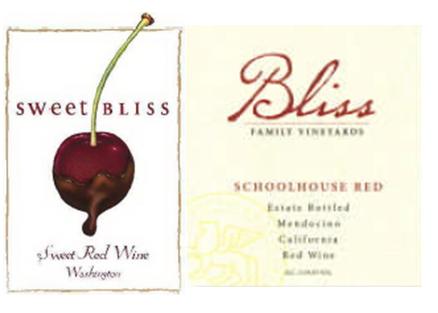

The declaratory judgment plaintiff’s wine label (left) and the defendant’s

The declaratory judgment plaintiff’s wine label (left) and the defendant’s

I guess I wasn’t in the mood to blog about wine.

It was right after New Year’s, after all.

On Jan. 4, West Richland, Wash., winery Pacific Rim Winemakers, Inc., filed suit in the Western District against the Hopeland, Calif., winery Brutocao Vineyards, Inc., for a declaration of noninfringement.

At issue is Pacific Rim’s SWEET BLISS and Brutocao’s BLISS trademarks.

Brutocao owns Reg. No. 3,187,029 for the BLISS word mark for “wines.”

Pacific Rim owns the application Serial No. 85,146,280 for the SWEET BLISS word mark for “wine.”

Pacific Rim alleges Brutocao sent it a letter alleging that SWEET BLISS would confuse the public into thinking that Pacific Rim’s wine comes from Brutocao. Pacific Rim, obviously, believes otherwise.

Brutocao has not yet answered the complaint.

The case cite is Pacific Rim Winemakers, Inc. v. Brutocao Vineyards, Inc., No. 11-0011 (W.D. Wash.).

Trademark Principles Not Appropriate in Determining "Voter Confusion"

On Jan. 11, the Western District took its final step in deciding whether the state’s new primary election system established by voter initiative I-872 is unconstitutional. Under the system, elections for partisan office start with a primary in which every candidate declares his or her party preference or independent status. Voters may select any candidate on the ballot, regardless of party preference, and the two candidates who receive the most votes, also regardless of party preference, advance to the general election. Thus, the general election becomes a runoff between the top two vote-getters in the primary.

In 2005, the Washington State Republican Party filed suit to enjoin I-872’s implementation. The Washington State Democratic Central Committee and Libertarian Party of Washington State intervened. After trips to the Ninth Circuit and Washington Supreme Court, the political parties amended their complaints to allege that I-872 is unconstitutional because it creates “voter confusion” that unconstitutionally infringes on their First Amendment associational freedoms.

Now, this is a trademark law blog, not an election law blog, so here’s why it’s of interest to trademark-oriented folks. The political parties argued the court should apply Lanham Act likelihood of confusion principles in determining the existence of voter confusion.

However, Western District Judge John Coughenour found trademark analysis was not helpful.

He wrote: the court “declines the political parties’ invitation to review the possibility for voter confusion under traditional trademark analysis. Quite simply, trademark law does not lie in the First Amendment associational rights implicated in this matter. Trademark law is designed to protect the proprietary rights of private parties from improper commercial uses. This case does not involve the propriety rights of the political parties or Washington’s commercial use of any trademark. The comparison is inapposite.”

The court also noted it previously concluded “the State’s expression of candidates’ party preference on the ballot and in the voter pamphlets may not form the basis of a federal or state trademark violation.”

(Not that it’s significant to trademark practitioners, but the court concluded that “Washington’s implementation of I-872 with respect to partisan offices is constitutional because the ballot and accompanying information concisely and clearly explain that a candidate’s political-party preference does not imply that the candidate is nominated or endorsed by the party or that the party approves of or associates with that candidate. These instructions — along with voters’ ability to understand campaign issues and the fact that the voters themselves approved the new election system through the initiative process — eliminate the possibility of widespread voter confusion and with it the threat to the First Amendment.”)

The case cite is Washington Republican Party v. Washington State Grange, 2011 WL 92032, No. 05-927 (W.D. Wash. Jan. 11, 2011) (Coughenour, J.).