Entries by Michael Atkins (1064)

Western District Denies Preliminary Injunction in Biotech Trademark Dispute

Plaintiff Mirina Corp. is a Seattle-area biotech company. In August 2010, it sued defendant Marina Biotech, a Seattle- and Boston-based biotech company, five days after defendant changed its name from MDRNA, Inc. (Previous post here.) Mirina alleged trademark infringement and moved for a preliminary injunction.

In doing so, it didn’t cite Winter v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 555 U.S. 7 (2008), which revised the standards for obtaining injunctive relief. The Western District of Washington found that was a problem.

“The court notes that the Plaintiff’s briefing was unhelpful regarding the appropriate standards to be applied on a motion for injunctive relief. The Plaintiff did not cite Winter authority until after the Defendant pointed out Plaintiff’s failure to do so in its Opposition. The Defendant had previously pointed out Plaintiff’s failure to address current case authority, and the court is mystified why the Plaintiff did not address the recent changes to standards for injunction relief in its opening brief. Though the Plaintiff attempts to argue that Winter and its progeny do not apply in trademark cases, Plaintiff cited no authority for that proposition and other district courts have applied Winter in trademark cases.”

The court set forth the test for a preliminary injunction, consistent with Winter and its progeny. “The court may issue a preliminary injunction where a party establishes (1) a likelihood of success n the merits, that (2) it is likely to suffer irreparable harm in the absence of preliminary relief, that (3) the balance of hardships tips in its favor, and (4) that the public interest favors an injunction. A party can satisfy the first and third elements of the test by raising serious questions going to the merits of its case and a balance of hardships that tips sharply in its favor.”

Analyzing the merits, the court found plaintiff’s motion didn’t cut it. “The court finds that, on balance, a consideration of the Sleekcraft factors weigh somewhat in Plaintiff’s favor, though not overwhelmingly so. The record before the court emphasizes phonetic similarity between the two business names and how that similarity leads to confusion in interpersonal conversations, but the court is left with some doubt as to whether this confusion is as widespread, invasive, or detrimental as Plaintiff’s selective evidence may make it appear, particularly where the evidence currently before the court shows that Plaintiff’s mark is relatively weak. Nonetheless, on that record, the court finds that the Plaintiff has raised serious questions about the likelihood of confusion.”

The case cite is Mirina Corp. v. Marina Biotech, No. 10-1322 (W.D. Wash. March 7, 2011) (Jones, J.).

Ninth Circuit Decides Competitor Keyword Advertising Case

Not much time to blog, as I’m preparing for my keyword panel discussion.

That said, the Ninth Circuit released a pretty juicy keyword decision Tuesday: Network Automation, Inc. v. Advanced Systems Concepts, Inc.

It holds the purchase of a competitor’s trademark constituted a “use” in commerce but didn’t infringe the trademark owner’s rights. The decision is filtered through the prism of the plaintiff’s motion for preliminary injunction, and the defendant is in a different position than Google in the recent Rosetta Stone case, but it seems to bode well for Google and other search engine providers.

The case cite is Network Automation, Inc. v. Advanced Systems Concepts, Inc., No. 10-55840 (9th Cir. March 8, 2011).

STL on Rosetta Stone v. Google - There's Still Time to Attend Thursday's Tele-CLE

On Thursday, STL’ll be talking about the status of keyword liability.

Sign up. There’s still time.

The tele-CLE is quick and to the point. In one hour, you’ll know everything that’s worth knowing about Rosetta Stone v. Google. Not because I’m on the panel. The two other speakers really know their stuff. (Moderator Jennifer A. Albert’s bio here; panelist Sheldon H. Klein’s bio here. I’m flattered to be included.)

This case is worth knowing about. When the Fourth Circuit weighs in, it will be the most influential keyword decision to date. The Eastern District of Virginia’s sweeping decision in favor of Google already is taught in law schools; it was part of my class and I’m by no means alone. It’s a big deal.

Brochure here. It’s $175 for 1.0 hour CLE credit.

Depiction of Betty Boop Cartoon Aesthetically Functional, Not Infringing

Betty Boop

Betty Boop

Depictions of the Betty Boop cartoon character are aesthetically functional and governed by copyright law. Therefore, they’re not protectable as trademarks.

The Ninth Circuit made those findings on Feb. 23.

Interestingly, it based its decision on two cases neither party cited in its briefs.

The Ninth Circuit affirmed the Central District of California’s summary judgment dismissal of plaintiff Fleischer Studios, Inc.’s trademark (and copyright) claims against defendant A.V.E.L.A., Inc., for reproducing the cartoon’s image on toys, dolls, and merchandise.

It found that International Order of Job’s Daughters v. Lindeburg & Co., 633 F.2d 912 (9th Cir. 1980), and Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 539 U.S. 23 (2003), barred plaintiff’s claims. Following Job’s Daughters, the court concluded “‘the articles themselves, the defendant’s merchandising practices, and any evidence that consumers have actually inferred a connection between the defendant’s product and the trademark owner,’ reveal that A.V.E.L.A. is not using Betty Boop as a trademark, but instead as a functional product.” In other words, consumers buy the good for the cartoon, not because the cartoon signifies it came from a particular source.

As for Dastar, the court concluded: “If we ruled that A.V.E.L.A.’s depictions of Betty Boop infringed Fleischer’s trademarks, the Betty Boop character would essentially never enter the public domain….” The Dastar court held that where a copyright is in the public domain, a party may not assert a trademark infringement action against an alleged infringer if that action is essentially a substitute for a copyright infringement action. Put another way, when a copyrighted work is at issue, an owner can’t do under trademark law what it can’t do can’t do under copyright law.

The court separately found that chain-of-title problems prevented Fleischer from enforcing rights under copyright law.

The case cite is Fleischer Studios, Inc. v. A.V.E.L.A., Inc., __ F.3d. __, 2011 WL 631449, No. 09-56317 (9th Cir. Feb. 23, 2011).

If Parody is Exempt from Dilution, Why isn't It Exempt from Infringement?

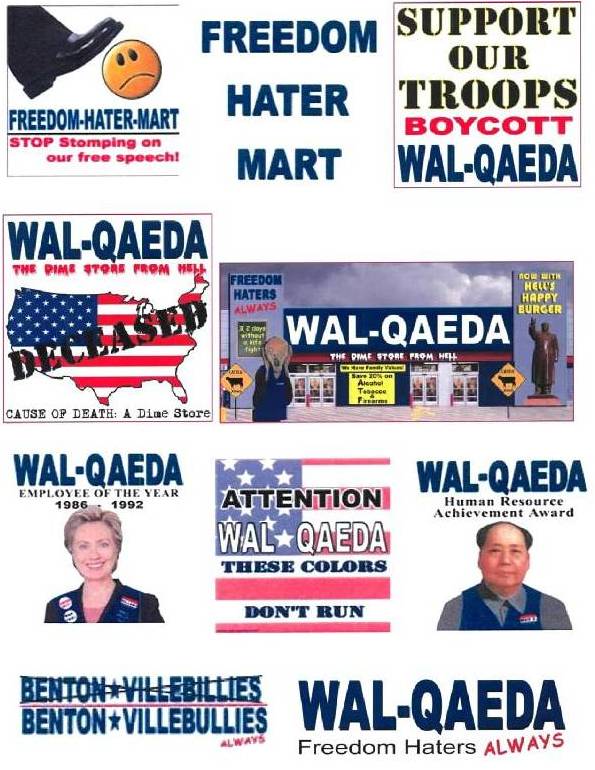

Not commerical, so no dilution: Charles Smith’s WAL-QAEDA parody

Not commerical, so no dilution: Charles Smith’s WAL-QAEDA parody

Discussing parody in my Advanced Trademark Law Seminar.

I’m stumped on one point.

In a number of cases involving the parodic use of a trademark, courts apply likelihood of confusion analysis to infringement claims. Successful parodies do not cause a likelihood of confusion, so they do not infringe trademark rights.

Analyzing dilution claims, however, courts in the same cases often treat parodies as noncommercial speech. For that reason, they conclude parodic uses are exempt from dilution claims.

In Smith v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 537 F.Supp.2d 1302 (N.D. Ga. 2008), for example, the court concluded Charles Smith’s use of WAL-QAEDA was not likely to confuse consumers with Wal-Mart’s trademarks, so Wal-Mart’s infringement claim against him could not stand. With respect to Wal-Mart’s dilution claim, the court found WAL-QAEDA succeeded as a parody because it communicated Mr. Smith’s negative feelings about Wal-Mart. “Thus, Smith’s parodic work is considered noncommercial speech and therefore not subject to Wal-Mart’s trademark dilution claims….” In other words, Mr. Smith’s parody did not trigger the dilution statute because it was noncommercial.

Similarly, in MasterCard Intern. Inc. v. Nader 2000 Primary Committee, Inc., 2004 WL 434404, *9 (S.D.N.Y.), the court found Ralph Nader’s use of MasterCard’s trademarks in a political ad that spoofed MasterCard’s “Priceless” advertising campaign was not likely to confuse consumers, so it dismissed MasterCard’s infringement claim. With regard to its dilution claim, the court concluded the Nader campaign’s use of MasterCard’s mark was “political in nature, not within a commercial context, and is therefore exempted from coverage by the Federal Trademark Dilution Act.” Again, noncommercial use did not trigger the statute (though this time it was because the ad was political, not because it was a parody).

The answer’s probably sitting there in McCarthy on Trademarks, but if a use that’s deemed noncommercial does not trigger the dilution portion of the Lanham Act, why does it trigger the infringement portion of the Lanham Act?

I realize the dilution portion of the statute expressly excepts parodic and noncommercial use — and infringement finds its roots in common law —but if my use of a trademark is deemed to be noncommercial, why do I have to go through likelihood of confusion analysis to determine if such use nonetheless infringes a trademark owner’s rights? Seems like a finding that my use is noncommercial would be the same “Get Out of Jail Free” card for infringement that it is for dilution.

Anyone willing to tell me why it’s not?