Entries by Michael Atkins (1064)

Ninth Circuit Changes Dilution Standard

Ninth Circuit: “Identical or nearly identical” doesn’t control.

Ninth Circuit: “Identical or nearly identical” doesn’t control.

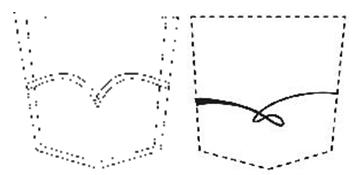

Levi’s and Abercrombie’s’ stitch designs

Interesting development in dilution in the Ninth Circuit.

Previously, Ninth Circuit courts required that a mark be “identical or nearly identical” to the plaintiff’s famous mark for dilution to exist.

That’s the standard the Northern District of California applied in Levi Strauss & Co. v. Abercrombie & Fitch Trading Company, a dilution case over the parties’ stitching designs. (STL post on the district court’s 2009 decision here.) The court noted the advisory jury had not found that Abercrombie’s “Ruehl” design and Levi’s “Arcuate” mark were “identical or nearly identical,” a standard that required that “the two marks … be similar enough that a significant segment of the target group of customers sees the two marks as essentially the same.” The district court likewise found the marks did not meet that standard and entered judgment for Abercrombie.

Levi Strauss appealed. It argued that nothing in the dilution statute requires the defendant’s mark be “identical or nearly identical.”

Abercrombie responded by arguing the subject language arose out of Ninth Circuit case law that continued to exist even after the Trademark Dilution Revision Act replaced the earlier Federal Trademark Dilution Act.

The Ninth Circuit considered the origin of the “identical or nearly identical” language. It found that even though the language predated the FTDA, the circuit embraced the standard because it believed it was rooted in that iteration of the statute. The court then noted the TDRA replaced the FTDA in broad strokes. That led the court to question whether a legacy standard should continue to control. It concluded the legacy standard was replaced when the FTDA was replaced.

“Several aspects of the TDRA are worth noting. The first, as mentioned previously, is that Congress did not merely make surgical linguistic changes to the FTDA in response to Moseley [v. V. Secret Catalogue, Inc., 537 U.S. 418 (2003), which required a showing of “actual dilution”]. Instead, Congress created a new, more comprehensive federal dilution act. Furthermore, any reference to the standards commonly employed by the courts of appeals — ‘identical,’ ‘nearly identical,’ or ‘substantially similar’ — are absent from the statute. The TDRA defines ‘dilution by blurring’ as the ‘association arising from the similarity between a mark or a trade name and a famous mark that impairs the distinctiveness of the famous mark.’ Moreover, in the non-exhaustive list of dilution factors that Congress set forth, the first is ‘[t]he degree of similarity between the mark or trade name and the famous mark.’ Thus, the text of the TDRA articulates a different standard for dilution from that which we utilized under the FTDA.”

The court found its departure from the “identical or nearly identical” standard was in line with the Second Circuit’s evaluation of Starbucks’ dilution claim based on use of the term CHARBUCKS for coffee in Starbucks Corp. v. Wolfe’s Borough Coffee, Inc., 588 F.3d 97 (2d Cir. 2009). In that case, the Second Circuit reversed the district court’s finding that the dissimilarity between CHARBUCKS and STARBUCKS was “sufficient to defeat [Starbucks’] blurring claim.” It instead found: “The post-TDRA federal dilution statute … provides us with a compelling reason to discard the ‘substantially similar’ requirement for federal dilution actions. … Although ‘similarity’ is an integral element in the definition of ‘blurring,’ we find it significant that the federal dilution statute does not use the words ‘very’ or ‘substantial’ in connection with the similarity factor to be considered in examining a federal dilution claim.”

In summary, a new statute means a new standard — or at least no basis for the Ninth Circuit’s old standard to live on. Therefore, the court reversed the district court’s decision and remanded for further proceedings.

The case cite is Levi Strauss & Co. v. Abercrombie & Fitch Trading Co., __ F.3d __, 2011 WL 383972, No. 09-16322 (9th Cir. Feb. 8, 2011).

Ninth Circuit Affirms Western District's Finding that "Vericheck" is Suggestive

A while back, the Western District in Lahoti v. Vericheck, Inc., found the VERICHECK trademark is suggestive when used in connection with check verification services. In doing so, it concluded that David Lahoti acted in bad faith when he registered the vericheck.com domain name.

In 2009, Mr. Lahoti appealed. The Ninth Circuit affirmed the bad faith finding. With regard to the classification of VERICHECK, it found: “[w]hile the district court perhaps could have relied exclusively on the registration of the Arizona Mark [also for VERICHECK for check verification services], it did not do so,” but instead “improperly required that the Mark describe all of [respondent] Vericheck’s services, examined the Mark in the abstract, and concluded that it could not analyze the Mark’s component parts.” Therefore, it vacated the district court’s judgment and remanded.

On remand, the Western District applied the Ninth Circuit’s direction in amended findings of fact and conclusions of law. It again concluded that VERICHECK is suggestive and, therefore, is entitled to protection as a trademark without a showing of secondary meaning.

Mr. Lahoti again appealed, arguing the district court again failed to analyze the VERICHECK mark in its industry context.

On Feb. 16, the Ninth Circuit affirmed. It found: “the district court indisputably recited the relevant legal principles that we set out. The district court then went on to find that, ‘[w]hen viewed in the context of Vericheck’s services, whether in whole or in part, including Vericheck’s check verification services, the VERICHECK mark does not immediately convey information about the nature of Vericheck’s services.’ The district court explained that, ‘in reaching [its] conclusion,’ it ‘considered the component parts of the VERICHECK mark ‘as a preliminary step on the way to an ultimate determination of the probable consumer reaction to the composite as a whole.” Thus, the district court conducted its analysis as instructed.”

STL background on the long-running case here, here, here and here.

The case cite is Lahoti v. Vericheck, Inc., __ F.3d. __, 2011 WL 540541, No. 10-35388 (9th Cir.) (Jan. 13, 2011).

Seattle eBay Seller's Lawsuit Against Coach Gets National Attention

Lots of media attention for Gina Kim’s class action lawsuit against Coach, Inc.

She says she used to work for Coach, had accumulated a few Coach handbags, and tried to sell them on eBay.

Ms. Kim says Coach accused her of selling counterfeit product and convinced eBay to pull her account. All without investigating whether her handbags were real or fake. So she sued for a declaratory judgment of noninfringement and for tortious interference with her relationship with eBay.

She now represents a class of persons she says have likewise been strong-armed by Coach.

AP story here; WSJ Law Blog post here.

It’s shameful if what Ms. Kim says is true. No matter how prevalent counterfeiting has gotten online, brand owners simply can’t assume all online sales of their goods are counterfeit. Accusing first and asking questions later just isn’t good policy. It’s against the law and suing innocent owners of the brand-owner’s product can’t be good for business.

Of course, Coach probably has a very different view of what allegedly happened.

We’ll see as the lawsuit unfolds — assuming it isn’t quickly settled.

PIE-brand Pie is the New CUPCAKE-brand Cupcake

Seattle pie maker Pie’s logo

Seattle pie maker Pie’s logo

And Seattle’s newest pie maker is Pie.

It stands to reason, then, that PIE-brand pie is the new CUPCAKE-brand cupcake.

Photo by STL

Western District Declares Portions of Personality Rights Act Unconstitutional

The expansive amendments to Washington’s Personality Rights Act (WPRA) that allowed anyone to sue in Washington to enforce their rights regardless of place of citizenship or domicile is unconstitutional.

That’s what Western District Judge Thomas Zilly decided today in Experience Hendrix LLC v. HendrixLicensing.com.ltd. (Previous posts on the case here, here and here; early posts on the WPRA amendments here and here.)

The statute, RCW 63.60, was amended in 2008 in part at the behest of the Estate of Jimi Hendrix, which sought a way to capture the value associated with the deceased musician’s personality. The Western District and Ninth Circuit previously found the estate possessed no such rights because Mr. Hendrix was domiciled in New York at the time of his death, which at the time did not recognize that a right of publicity was capable of descending to a person’s heirs after death.

The amendment in part stated that Washington recognized a right of publicity “regardless of whether the law of the domicile, residence, or citizenship of the individual or personality at the time of death or otherwise recognizes a similar or identical property right.”

The defendants challenged the constitutionality of the amendments after being sued for using Mr. Hendrix’s name and signature in connection with the sale of Hendrix-themed artwork without the estate’s permission.

In a 47-page opinion, the court found the amendment’s choice-of-law provision violated the Due Process, Full Faith and Credit, and “dormant” Commerce Clauses of the U.S. Constitution.

The court explained the bulk of its reasoning as follows:

“Not only is Washington’s choice-of-law directive at odds with the almost unanimous views of courts that have grappled with the survivability of the right of publicity, it also runs contrary to the traditional approach for resolving the testamentary or intestate disposition of personal property. This status as an outlier evidences the arbitrariness of the WPRA’s choice-of-law provision and portends of the potential unfair ramifications of its application. Courts look to the law of the domicile for a reason. The domicile has the requisite contacts with a particular individual or personality to generate a state interest in defining his or her property rights and how they may be transferred. To select, as the WPRA suggests, the law of a state to which the individual or personality is a stranger, constitutes no less random an act than blindly throwing darts at a map on the wall.

“This capriciousness will likely lead to inconsistent and unjust results. Indiana is the only state other than Washington that attempts by statute to disregard the law of the domicile. Thus, with respect to a personality who was domiciled in New York at the time of death, Washington and Indiana would stand alone in disregarding New York law abating such personality’s right of publicity, and any entity using such personality’s likeness for commercial purposes would be subject to contradictory standards.

“Efforts to avoid litigation by, for example, restricting sales to the 48 states honoring New York law would be futile. Under the WPRA, advertisements alone provide a basis for suit, regardless of whether they are disseminated in the forum. In addition, putative plaintiffs will be motivated to divert sales to Washington to obtain the benefits of the WPRA. Finally, under existing case law, specific jurisdiction as to intentional conduct occurring outside the forum may be predicated solely on the ‘effects’ within the forum.

“Applying the law of the domicile produces none of these negative consequences. An individual or personality can have only one domicile at a given time. The domicile at the time of death is a constant, based upon which the scope and survivability of any right of publicity may be derived, even if the law of the domicile is in flux concerning such issues. Once determined under the law of the domicile in effect at the relevant time, the existence or absence of a post-mortem right of publicity is known with respect to all jurisdictions, and an entity seeking to exploit a persona that has passed into the public domain need not engage in any state-specific self-censorship. Moreover, adhering to the ‘majority’ domicile-oriented rule would eliminate the incentive for putative plaintiffs to forum shop. Given the arbitrary and unfair nature of the WPRA’s choice-of-law directive concerning the existence of a post-mortem right of publicity, the Court GRANTS partial summary judgment in favor of defendants on their first declaratory judgment counterclaim and hereby DECLARES that such provision violates the Due Process and Full Faith and Credit Clauses of the United States Constitution.”

The court added: “The same provisions of the WPRA found to be in violation of the Due Process and Full Faith and Credit Clauses, as enumerated earlier, are also deemed unconstitutional pursuant to the extraterritorial doctrine derived from the dormant Commerce Clause.”

The order invalidates the choice-of-forum clauses of RCW 63.60.010, .020(1), .020(2), .030(1)(a), and .030(1)(b)(iv).

I would imagine the order is certain to be appealed.

The case cite is Experience Hendrix, L.L.C. v. HendrixLicensing.Com, Ltd., No. 09-285 (W.D. Wash. Feb. 8, 2011) (Zilly, J.).